Back

Abstract Session

Immunobiology

Session: Abstracts: Cytokines and Cell Trafficking (0558–0561)

0559: JAK Inhibitor Withdrawal Causes a Transient Proinflammatory Signaling Cascade in Minor Salivary Gland Mesenchymal Stromal Cells

Sunday, November 13, 2022

8:15 AM – 8:25 AM Eastern Time

Location: Room 103

.png)

Sara McCoy, MD, PhD, RhMSUS

University of Wisconsin

Middleton, WI, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Ilya Gurevic, jacques Galipeau and Sara McCoy, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI

Background/Purpose: Sjögren's Disease (SjD) has high glandular IFNg levels, associated with disease activity and lymphoma risk. We previously showed IFNg-stimulated minor salivary gland (SG)-mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) produce CXCL-9, -10, and -11 through JAK2→STAT1 phosphorylation. Chemokine production and STAT1 phosphorylation by SG MSCs were inhibited by the JAK1/2 inhibitor, ruxolitinib, that may represent a promising therapy for SjD. Using culture adapted SG MSC as an in vitro rosetta stone of SG-resident parenchymal cells, we investigated the IFNg →JAK/STAT biochemical response of SG-MSCs to FDA approved JAK inhibitors.

Methods: We treated SG MSCs from control subjects and SjD patients with 10 ng/mL IFNg and JAK1/2 inhibitors. The JAK inhibitors included ruxolitinib and baricitinib, which bind the JAK conformation poised to phosphorylate its STAT substrates (kinase active conformation). We also studied the novel JAK inhibitor, CHZ868, which binds the kinase inactive JAK conformation. We used varying doses and durations of these three JAK inhibitors. We performed western blotting of cell lysates, probing for JAK1, JAK2, STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 and their respective phosphorylated states. We collated western blot data by normalizing to the IFNg treatment condition or relative to the maximum inhibitor condition. We performed ANOVA to calculate p-values across multiple variables.

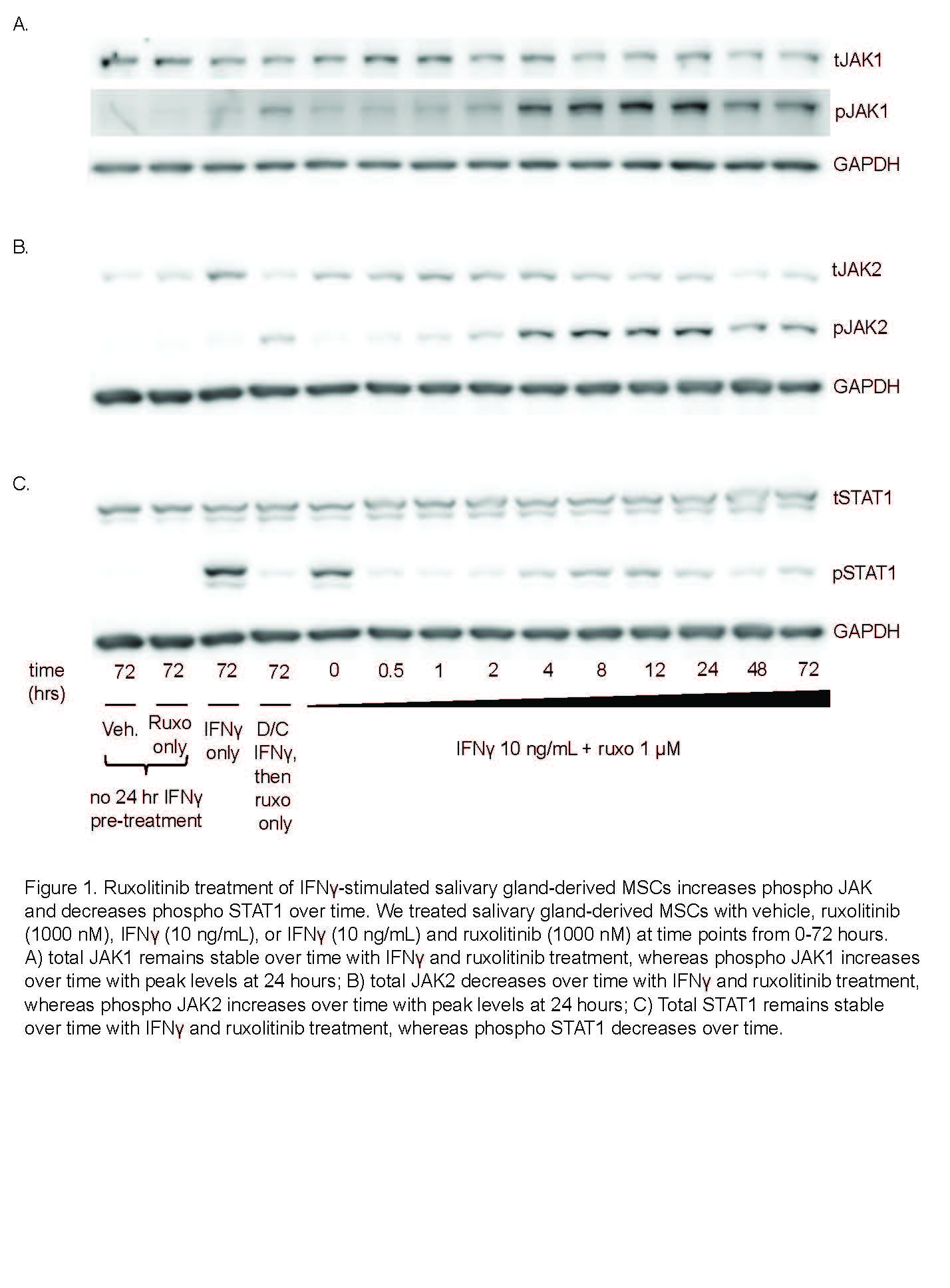

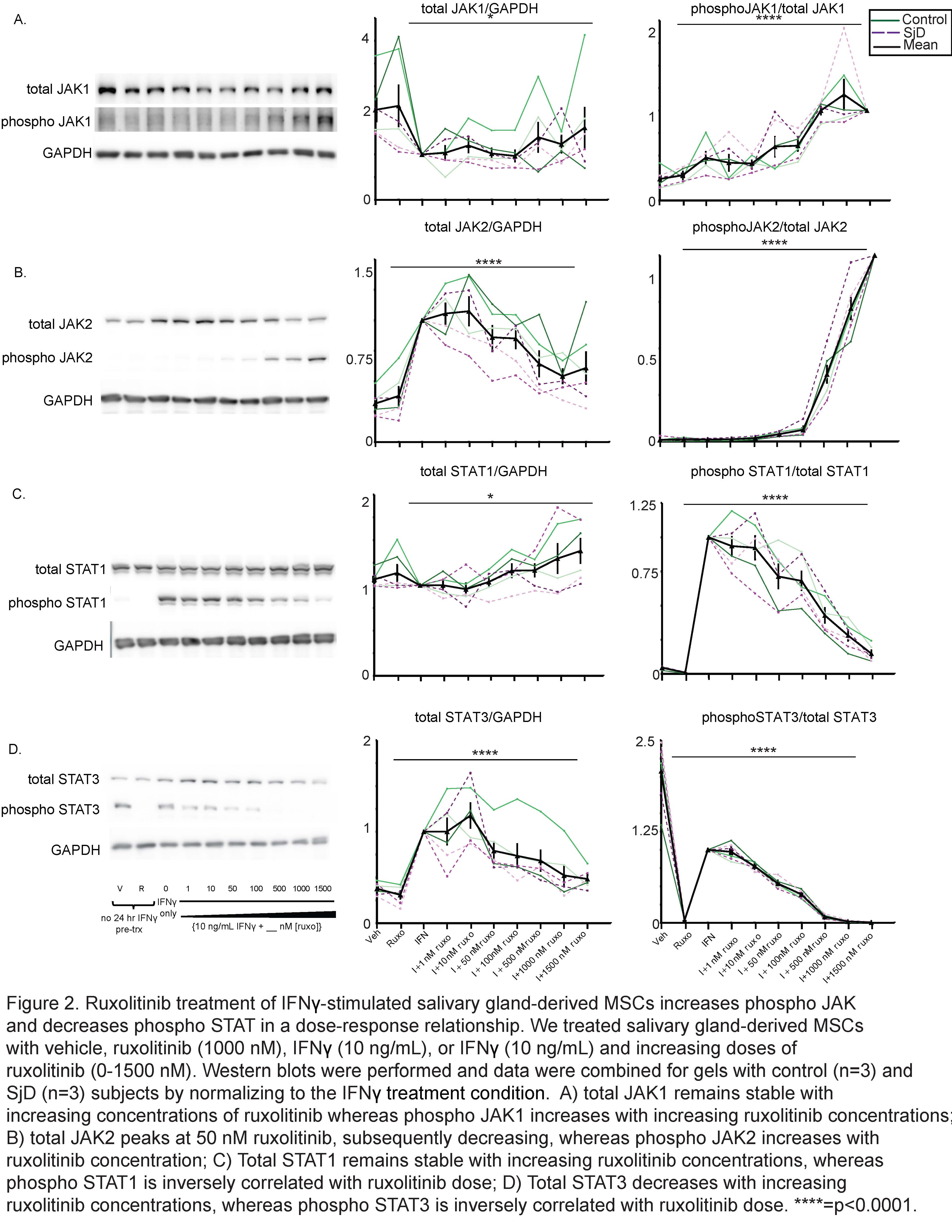

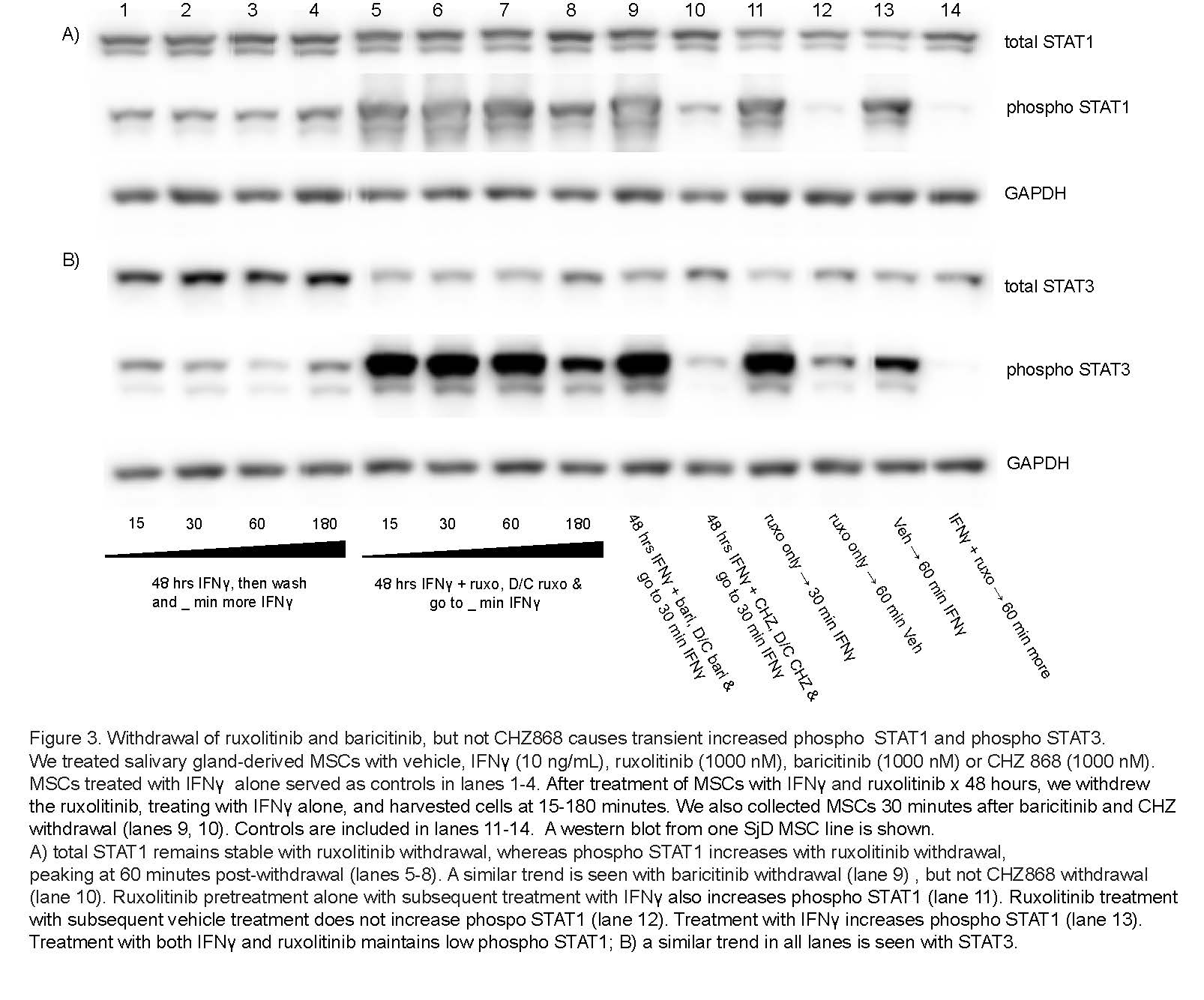

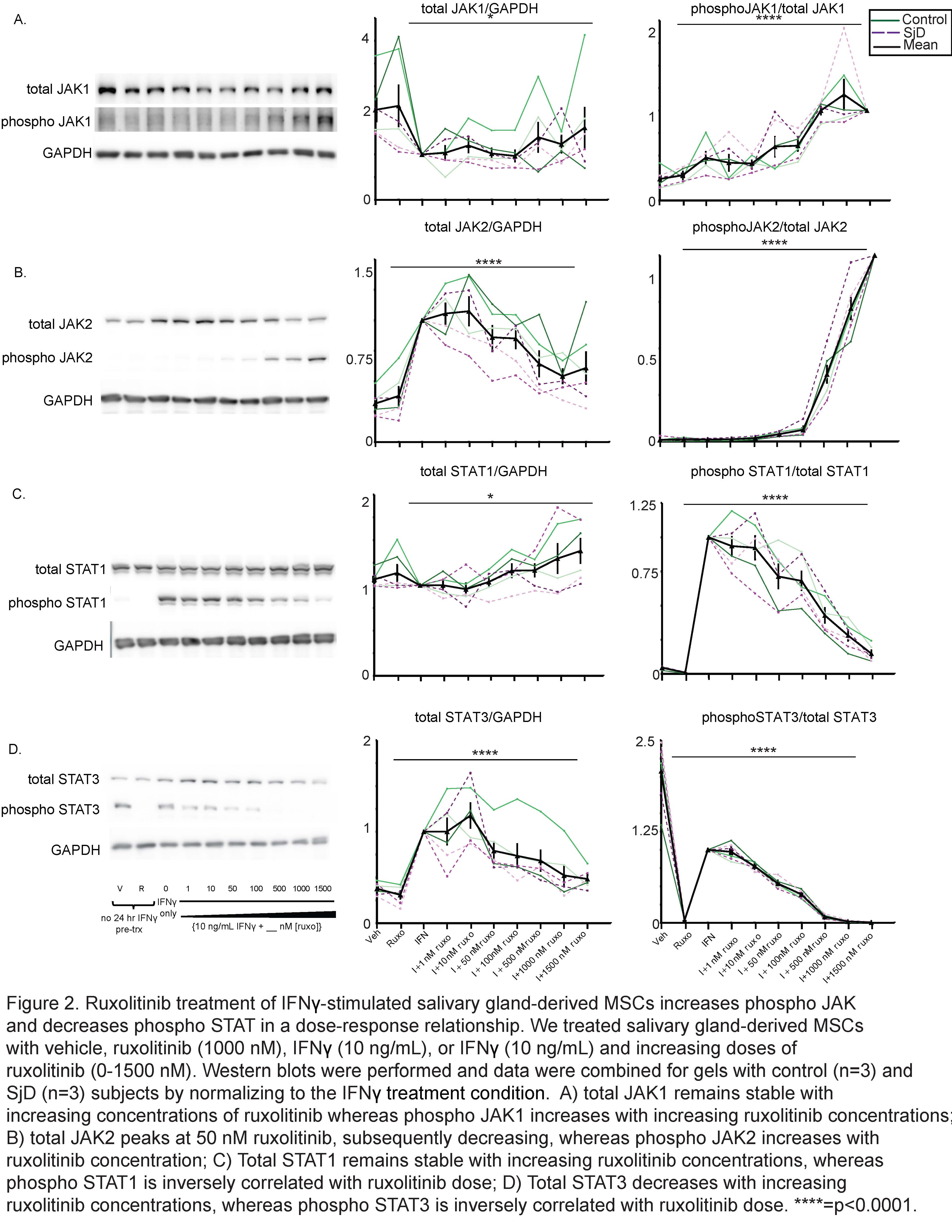

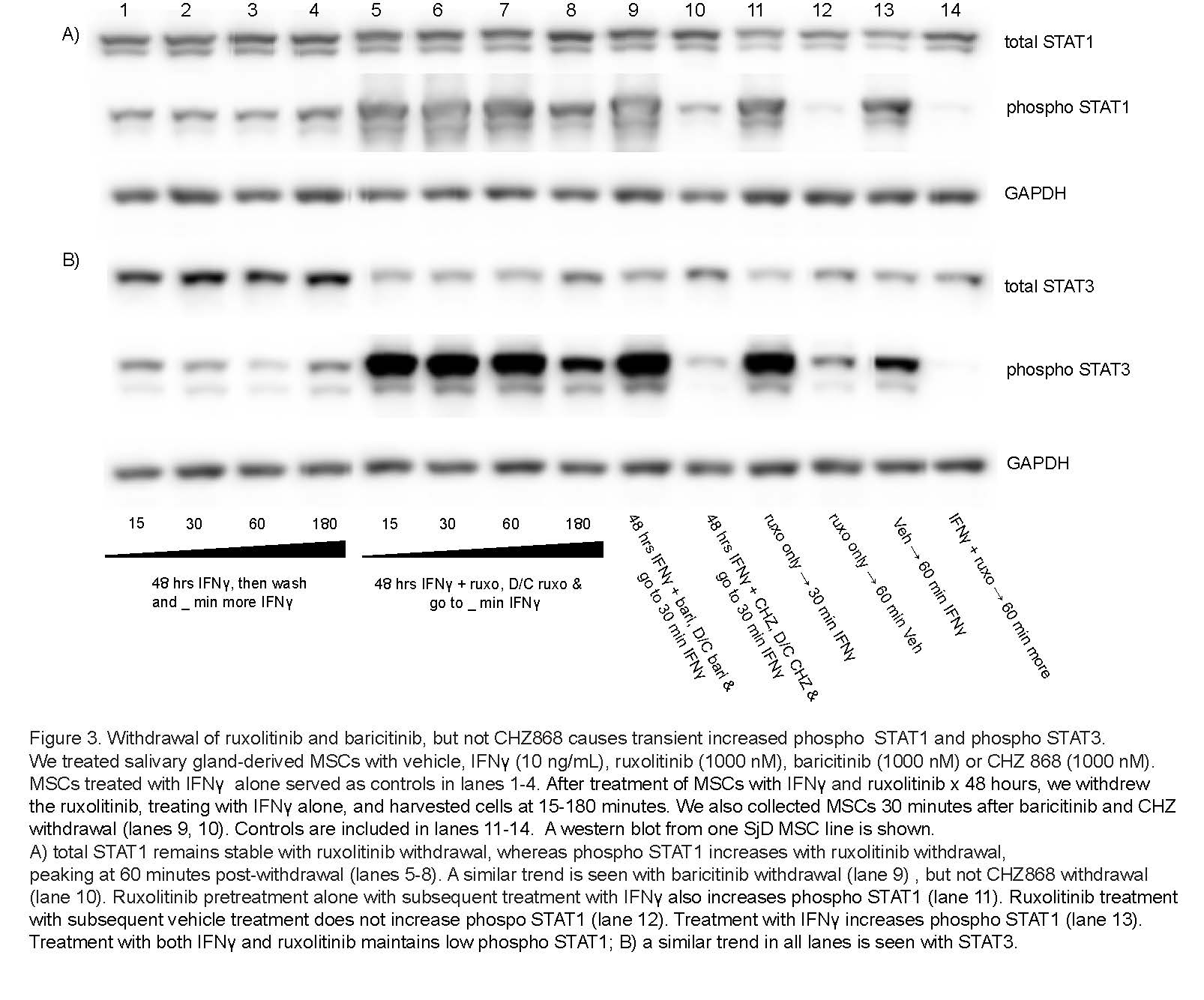

Results: We determined that ruxolitinib treatment increased phospho JAK1 (pJAK1) and phospho JAK2 (pJAK2) of IFNg-stimulated SG-MSCs in a time dependent manner, with effect peaking after 24 hours (Fig 1a-b). As expected, pSTAT1 was completely suppressed by ruxolitinib immediately upon treatment (Fig 1c). Further, adding ruxolitinib to IFNg-stimulated SG-MSCs markedly increased pJAK1 (p< 0.0001)) and pJAK2 (p< 0.0001)) in a dose response relationship (Fig 2a-2b). As expected, pSTAT1 (p< 0.0001) and pSTAT3 (p< 0.005)) decreased with increasing ruxolitinib (Fig 2c). These finding were similar in both control and SjD SG-MSCs. Interestingly, we found a marked and rapid increase of pSTAT1 and pSTAT3 upon discontinuation of ruxolitinib and baricitinib, but not CHZ868, regardless of whether we maintained or stopped IFNg stimulation (Fig 3).

Conclusion: Our findings suggest that ruxolitinib and baricitinib, by binding the active phosphorylated form of JAK lead to a paradoxical cellular accumulation of functionally defective pJAK. Upon inhibitor withdrawal, the primed pJAKs are de-repressed and initiate a pSTAT signaling cascade. In contrast, CHZ868, which binds the inactive JAK kinase conformation, does not lead to pJAK accumulation. Further, CHZ868 does not cause increased pSTAT upon withdrawal. In conclusion, JAK1/2 inhibitors that bind the active pJAK configuration, but not those that bind the inactive JAK configuration, increase STAT signaling on withdrawal. We propose this as a novel mechanism contributing to the rebound pro-inflammatory effects of JAK1/2 inhibitors that associate with the active JAK conformation. Future directions include further analysis of JAK inhibitors on MSC influence in shaping the immune response in health and disease.

Disclosures: I. Gurevic, None; j. Galipeau, None; S. McCoy, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS).

Background/Purpose: Sjögren's Disease (SjD) has high glandular IFNg levels, associated with disease activity and lymphoma risk. We previously showed IFNg-stimulated minor salivary gland (SG)-mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) produce CXCL-9, -10, and -11 through JAK2→STAT1 phosphorylation. Chemokine production and STAT1 phosphorylation by SG MSCs were inhibited by the JAK1/2 inhibitor, ruxolitinib, that may represent a promising therapy for SjD. Using culture adapted SG MSC as an in vitro rosetta stone of SG-resident parenchymal cells, we investigated the IFNg →JAK/STAT biochemical response of SG-MSCs to FDA approved JAK inhibitors.

Methods: We treated SG MSCs from control subjects and SjD patients with 10 ng/mL IFNg and JAK1/2 inhibitors. The JAK inhibitors included ruxolitinib and baricitinib, which bind the JAK conformation poised to phosphorylate its STAT substrates (kinase active conformation). We also studied the novel JAK inhibitor, CHZ868, which binds the kinase inactive JAK conformation. We used varying doses and durations of these three JAK inhibitors. We performed western blotting of cell lysates, probing for JAK1, JAK2, STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 and their respective phosphorylated states. We collated western blot data by normalizing to the IFNg treatment condition or relative to the maximum inhibitor condition. We performed ANOVA to calculate p-values across multiple variables.

Results: We determined that ruxolitinib treatment increased phospho JAK1 (pJAK1) and phospho JAK2 (pJAK2) of IFNg-stimulated SG-MSCs in a time dependent manner, with effect peaking after 24 hours (Fig 1a-b). As expected, pSTAT1 was completely suppressed by ruxolitinib immediately upon treatment (Fig 1c). Further, adding ruxolitinib to IFNg-stimulated SG-MSCs markedly increased pJAK1 (p< 0.0001)) and pJAK2 (p< 0.0001)) in a dose response relationship (Fig 2a-2b). As expected, pSTAT1 (p< 0.0001) and pSTAT3 (p< 0.005)) decreased with increasing ruxolitinib (Fig 2c). These finding were similar in both control and SjD SG-MSCs. Interestingly, we found a marked and rapid increase of pSTAT1 and pSTAT3 upon discontinuation of ruxolitinib and baricitinib, but not CHZ868, regardless of whether we maintained or stopped IFNg stimulation (Fig 3).

Conclusion: Our findings suggest that ruxolitinib and baricitinib, by binding the active phosphorylated form of JAK lead to a paradoxical cellular accumulation of functionally defective pJAK. Upon inhibitor withdrawal, the primed pJAKs are de-repressed and initiate a pSTAT signaling cascade. In contrast, CHZ868, which binds the inactive JAK kinase conformation, does not lead to pJAK accumulation. Further, CHZ868 does not cause increased pSTAT upon withdrawal. In conclusion, JAK1/2 inhibitors that bind the active pJAK configuration, but not those that bind the inactive JAK configuration, increase STAT signaling on withdrawal. We propose this as a novel mechanism contributing to the rebound pro-inflammatory effects of JAK1/2 inhibitors that associate with the active JAK conformation. Future directions include further analysis of JAK inhibitors on MSC influence in shaping the immune response in health and disease.

Disclosures: I. Gurevic, None; j. Galipeau, None; S. McCoy, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS).