Back

Purpose: Vitamin E acetate was used in the production of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) e-cigarettes or vaping products and detected in many bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples from patients with the e-cigarette or vaping product use associated lung injury (EVALI). Hence, vitamin E acetate is considered to be a prime potential culprit of the EVALI outbreak of marijuana and THC vaping. However, there are few data explaining how vitamin E acetate contributed to the outbreak. The aim of this study was to conduct in vitro and in vivo studies to investigate the role of vitamin E acetate in the marijuana/THC 2019 EVALI outbreak.

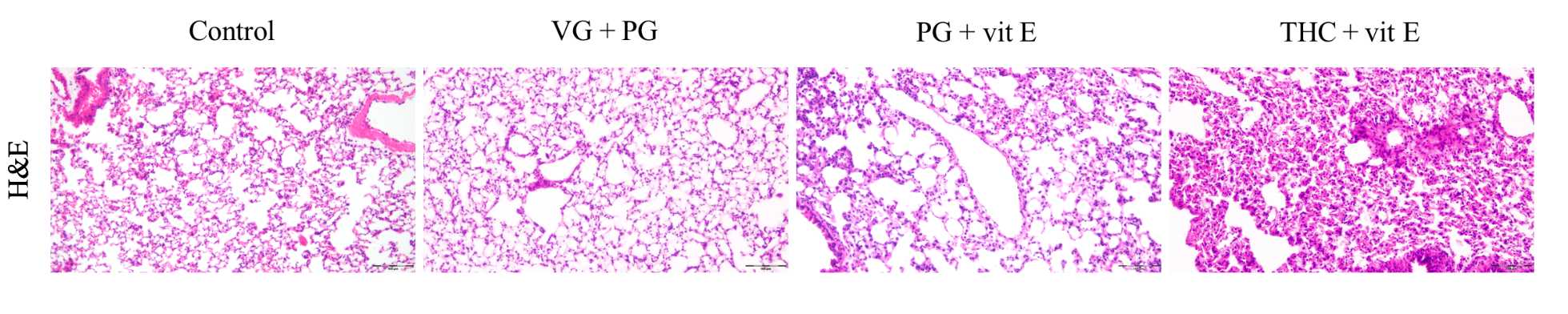

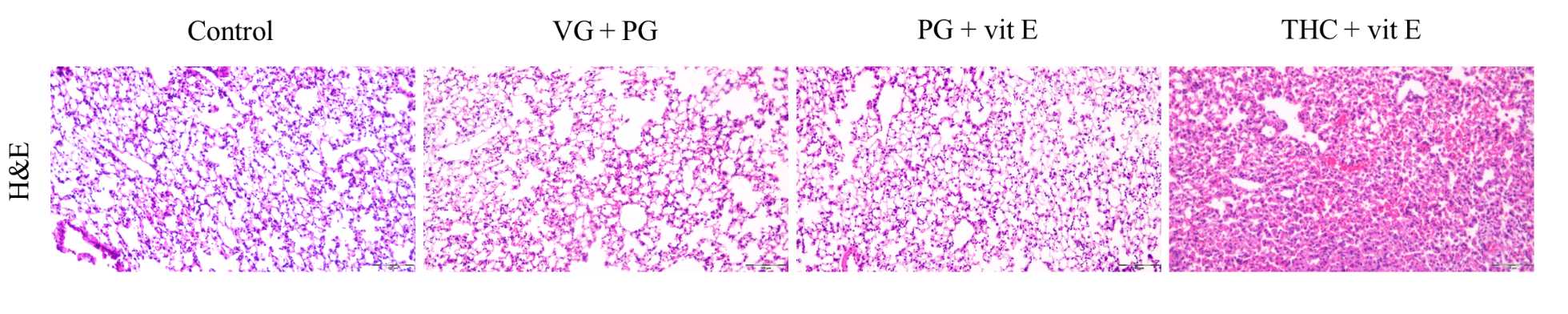

Methods: In vitro - The affinities of THC for cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2R) were examined using displacement assays. Briefly, cell membranes from the Chinese hamster ovary(CHO) cells expressing human CB2Rs were isolated through differential centrifugation. THC in propylene glycol (PG) with and without vitamin E acetate (vit E) were incubated with the isolated membrane in binding buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, 1.0 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 3 mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2), 5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), pH 7.4] along with 2.5 nM [3H] CP-55,940. The total binding was assessed in the presence of equal concentrations of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), whereas nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM [3H] CP-55,940, and background binding was determined in wells lacking a membrane. After incubation at 30 °C for 60 minutes, the binding reactions were terminated by filtration through Whatman GF/C filters. The filters were then washed twice with an ice-cold buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mg/mL BSA). A liquid scintillation cocktail was added to each well and the total tritiated counts per minute were analyzed by using a TopCount scintillation counter. Background counts were subtracted from all wells and the percent displacement from total binding was calculated. THC was screened at 4–250 μg/mL of propylene glycol (PG) concentrations alone or in the presence of 50% vitamin E acetate. GraphPad Prism 9.3.1 (350) was used to calculate the half maximal effective concentration (EC50). In vivo study - All animal experiments were approved by the University of Mississippi’s IACUC protocol # 20-014. Male and female mice were each randomly assigned into 4 groups with 5 mice for each group, and each was separately treated with control (no smoke), propylene glycol + vegetable glycerin (VG) (50:50, v/v), propylene glycol + vitamin E acetate (50:50, v/v), and 250 g/mL/mouse of THC in propylene glycol + vitamin E acetate (50:50, v/v) by using e-cigarette type cartridges in controlled modified cages to a 40 min exposure session. At the end of the in vivo assessment, these mice were sacrificed and tissues were collected. Lungs were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde, embedded with paraffin, and cut into 5-μm thick sections for further H&E staining and microscopic observation.

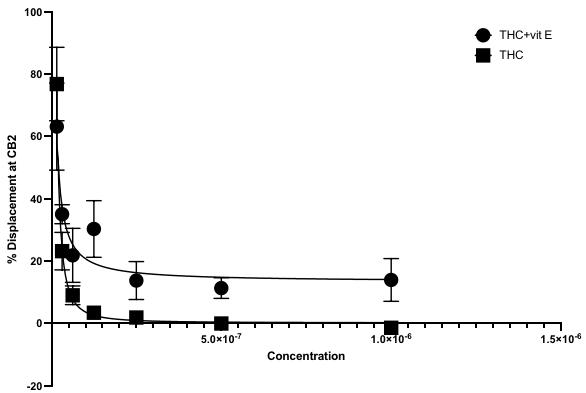

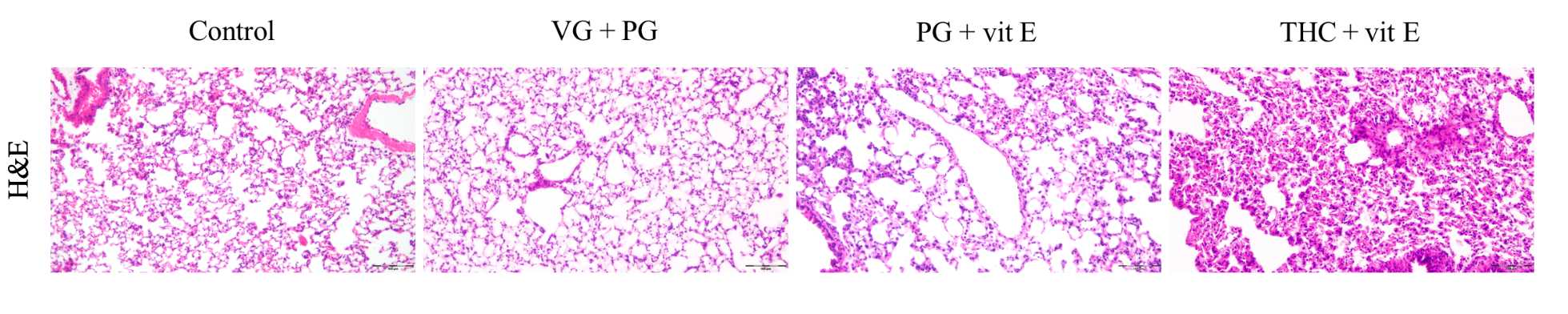

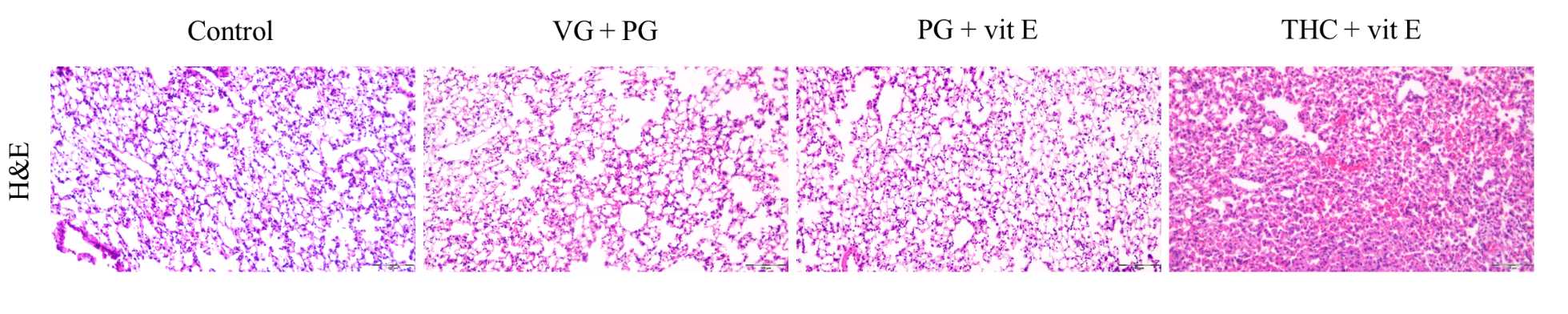

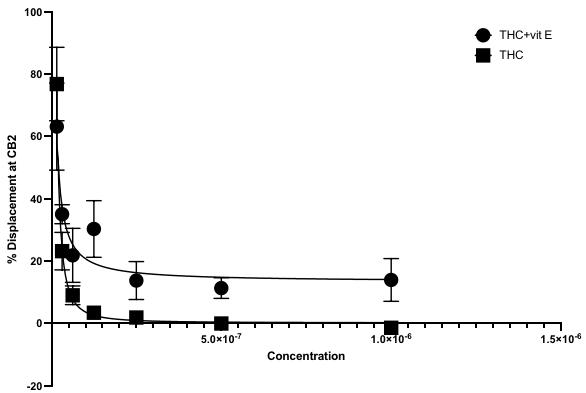

Results: In vitro study - At concentrations ranging from 31.25 µg/mL to 250 µg/mL, THC with vitamin E acetate exhibited less capability of displacing [3H] CP-55,940 and binding to CB2R by up to 20% (EC50=4.97 µg/mL) compared with THC without vitamin E acetate ( EC50=5.62 µg/mL) with n=3/assay. However, there was no significant displacement at lower concentrations in the presence of vitamin E acetate (Figure 1). In vivo study - As shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, there were marked signs of inflammation with some dense tissues that suggested fibrosis in the THC + vitamin E acetate group compared to other groups.

Conclusion: The in vitro study demonstrates that vitamin E acetate can decrease the binding of THC with the CB2R. In addition, a more severe inflammatory response can be observed in the vitamin E acetate and THC co-administration group (from the H&E stained images) compared to the other groups. Therefore, vitamin E acetate may reduce the CB2-mediated anti-inflammatory response, making patients more susceptible to the inflammation and may thereby lead to an outbreak of EVALI.

Figure 1. The binding affinity of THC to CB2R with and without vitamin E acetate.

Figure 2. Microscopic imagines of H&E stained lung sections of the male group.

Figure 3. Microscopic imagines of H&E stained lung sections of the female group.

Preclinical Development - Chemical - Safety

Category: Late Breaking Poster Abstract

(M0930-02-12) In Vitro and In Vivo Assessment of Vitamin E Acetate’s Potential Role in Causing the Marijuana/THC 2019 EVALI Outbreak

Monday, October 17, 2022

9:30 AM – 10:30 AM ET

- ML

Mengwen Li, MS

University of Mississippi

Oxford, Mississippi, United States - ML

Mengwen Li, MS

University of Mississippi

Oxford, Mississippi, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Main Author(s)

Purpose: Vitamin E acetate was used in the production of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) e-cigarettes or vaping products and detected in many bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) samples from patients with the e-cigarette or vaping product use associated lung injury (EVALI). Hence, vitamin E acetate is considered to be a prime potential culprit of the EVALI outbreak of marijuana and THC vaping. However, there are few data explaining how vitamin E acetate contributed to the outbreak. The aim of this study was to conduct in vitro and in vivo studies to investigate the role of vitamin E acetate in the marijuana/THC 2019 EVALI outbreak.

Methods: In vitro - The affinities of THC for cannabinoid receptor 2 (CB2R) were examined using displacement assays. Briefly, cell membranes from the Chinese hamster ovary(CHO) cells expressing human CB2Rs were isolated through differential centrifugation. THC in propylene glycol (PG) with and without vitamin E acetate (vit E) were incubated with the isolated membrane in binding buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl, 1.0 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 3 mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2), 5 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), pH 7.4] along with 2.5 nM [3H] CP-55,940. The total binding was assessed in the presence of equal concentrations of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), whereas nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of 10 μM [3H] CP-55,940, and background binding was determined in wells lacking a membrane. After incubation at 30 °C for 60 minutes, the binding reactions were terminated by filtration through Whatman GF/C filters. The filters were then washed twice with an ice-cold buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mg/mL BSA). A liquid scintillation cocktail was added to each well and the total tritiated counts per minute were analyzed by using a TopCount scintillation counter. Background counts were subtracted from all wells and the percent displacement from total binding was calculated. THC was screened at 4–250 μg/mL of propylene glycol (PG) concentrations alone or in the presence of 50% vitamin E acetate. GraphPad Prism 9.3.1 (350) was used to calculate the half maximal effective concentration (EC50). In vivo study - All animal experiments were approved by the University of Mississippi’s IACUC protocol # 20-014. Male and female mice were each randomly assigned into 4 groups with 5 mice for each group, and each was separately treated with control (no smoke), propylene glycol + vegetable glycerin (VG) (50:50, v/v), propylene glycol + vitamin E acetate (50:50, v/v), and 250 g/mL/mouse of THC in propylene glycol + vitamin E acetate (50:50, v/v) by using e-cigarette type cartridges in controlled modified cages to a 40 min exposure session. At the end of the in vivo assessment, these mice were sacrificed and tissues were collected. Lungs were then fixed with 4% formaldehyde, embedded with paraffin, and cut into 5-μm thick sections for further H&E staining and microscopic observation.

Results: In vitro study - At concentrations ranging from 31.25 µg/mL to 250 µg/mL, THC with vitamin E acetate exhibited less capability of displacing [3H] CP-55,940 and binding to CB2R by up to 20% (EC50=4.97 µg/mL) compared with THC without vitamin E acetate ( EC50=5.62 µg/mL) with n=3/assay. However, there was no significant displacement at lower concentrations in the presence of vitamin E acetate (Figure 1). In vivo study - As shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, there were marked signs of inflammation with some dense tissues that suggested fibrosis in the THC + vitamin E acetate group compared to other groups.

Conclusion: The in vitro study demonstrates that vitamin E acetate can decrease the binding of THC with the CB2R. In addition, a more severe inflammatory response can be observed in the vitamin E acetate and THC co-administration group (from the H&E stained images) compared to the other groups. Therefore, vitamin E acetate may reduce the CB2-mediated anti-inflammatory response, making patients more susceptible to the inflammation and may thereby lead to an outbreak of EVALI.

Figure 1. The binding affinity of THC to CB2R with and without vitamin E acetate.

Figure 2. Microscopic imagines of H&E stained lung sections of the male group.

Figure 3. Microscopic imagines of H&E stained lung sections of the female group.