Back

Neurocognitive Disorders, Delirium and Neuropsychiatry

Poster Session

(055) "It's All In Your Head": Abnormal Visual Processing During Magnetoencephalography Is Associated with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury In US Veterans

Abstract:

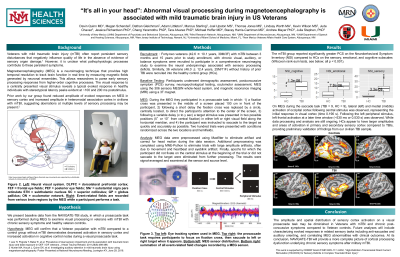

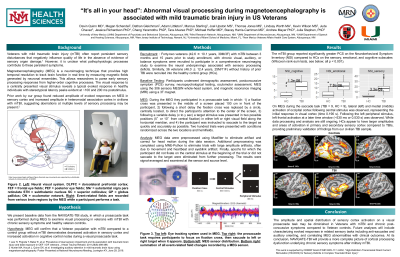

Background: Individuals with mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) often report persistent sensory disturbances that negatively influence quality of life. However, it is unclear whether these sensory deficits are related to functional stress responses or to physiological alterations in basic sensory processing. Magnetoencephalography (MEG) is a neuroimaging technique that provides high temporal resolution to track brain function in real time and parse early sensory processing responses from higher-order cognitive processes; prior work by our group found reduced amplitudes of auditory evoked responses in primary sensory cortex in civilians with mTBI. In the NAVIGATE-TBI study a prosaccade task was performed during MEG to examine basic visual processing in Veterans with mTBI with chronic sensory symptoms and healthy controls.

Methods: Twenty-four Veterans (43.4 ± 10.5 years, 22M/2F) with chronic mTBI and ongoing sensory symptoms were recruited along with 17 Veterans (46.9 ± 10.2 years, 12M/5F) without prior TBI. Participants underwent postconcussive symptom (PCS) survey, neurosensory assessment, and MEG using the Elekta Neuromag 306-sensor whole-head system. During MEG participants performed a prosaccade task in which a target stimulus was presented 5° or 10° from central fixation in either left or right visual field. Participants were instructed to saccade to the target as quickly and accurately as possible. Two hundred trials were presented with conditions randomized across the two locations and hemifields. MEG data were preprocessed to eliminate head motion and heartbeat and eyeblink artifact and results were signal-averaged and examined at the sensor and source level.

Results: The visual evoked response typically peaks at ~100 and 200 ms poststimulus. The mTBI group reported significantly greater PCS (p < 0.001) as well as significantly more provoked symptoms such as nausea and dizziness after horizontal saccades compared to controls (p < 0.001). During MEG there were no significant differences between groups in eye tracking measures for number of correct saccades, average or peak amplitude of saccades, or average or peak velocity of saccades (all p > 0.1). However, Veterans with mTBI revealed significantly reduced M100 and M200 evoked response amplitudes in occipital regions relative to controls for the central visual stimulus (p < .05), largely due to variability in the peak response.

Discussion: The timing of sensory responses is sensitive to the underlying anatomy that connects the eye to the visual cortex. In this case, variability in the M100 and M200 responses in the mTBI group may reveal compromises in the optic radiations or effects of mTBI within visual cortex. Heterogeneity of injury characteristics in the mTBI group, including number of injuries and sensory symptom severity, may be contributing factors. Our findings suggest objective deficits in sensory functioning underly chronic PCS in Veteran populations. Future analyses will correlate MEG abnormalities with structural MRI.

Background: Individuals with mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) often report persistent sensory disturbances that negatively influence quality of life. However, it is unclear whether these sensory deficits are related to functional stress responses or to physiological alterations in basic sensory processing. Magnetoencephalography (MEG) is a neuroimaging technique that provides high temporal resolution to track brain function in real time and parse early sensory processing responses from higher-order cognitive processes; prior work by our group found reduced amplitudes of auditory evoked responses in primary sensory cortex in civilians with mTBI. In the NAVIGATE-TBI study a prosaccade task was performed during MEG to examine basic visual processing in Veterans with mTBI with chronic sensory symptoms and healthy controls.

Methods: Twenty-four Veterans (43.4 ± 10.5 years, 22M/2F) with chronic mTBI and ongoing sensory symptoms were recruited along with 17 Veterans (46.9 ± 10.2 years, 12M/5F) without prior TBI. Participants underwent postconcussive symptom (PCS) survey, neurosensory assessment, and MEG using the Elekta Neuromag 306-sensor whole-head system. During MEG participants performed a prosaccade task in which a target stimulus was presented 5° or 10° from central fixation in either left or right visual field. Participants were instructed to saccade to the target as quickly and accurately as possible. Two hundred trials were presented with conditions randomized across the two locations and hemifields. MEG data were preprocessed to eliminate head motion and heartbeat and eyeblink artifact and results were signal-averaged and examined at the sensor and source level.

Results: The visual evoked response typically peaks at ~100 and 200 ms poststimulus. The mTBI group reported significantly greater PCS (p < 0.001) as well as significantly more provoked symptoms such as nausea and dizziness after horizontal saccades compared to controls (p < 0.001). During MEG there were no significant differences between groups in eye tracking measures for number of correct saccades, average or peak amplitude of saccades, or average or peak velocity of saccades (all p > 0.1). However, Veterans with mTBI revealed significantly reduced M100 and M200 evoked response amplitudes in occipital regions relative to controls for the central visual stimulus (p < .05), largely due to variability in the peak response.

Discussion: The timing of sensory responses is sensitive to the underlying anatomy that connects the eye to the visual cortex. In this case, variability in the M100 and M200 responses in the mTBI group may reveal compromises in the optic radiations or effects of mTBI within visual cortex. Heterogeneity of injury characteristics in the mTBI group, including number of injuries and sensory symptom severity, may be contributing factors. Our findings suggest objective deficits in sensory functioning underly chronic PCS in Veteran populations. Future analyses will correlate MEG abnormalities with structural MRI.

Davin Quinn, MD FACLP

Professor of Psychiatry

University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center

Albuquerque, New Mexico, United States