Back

Poster, Podium & Video Sessions

Podium

PD59: Kidney Cancer: Advanced (including Drug Therapy) II

PD59-03: Adjuvant Therapy After Surgical Resection of Nonmetastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma: one size does not fit all

Monday, May 16, 2022

1:20 PM – 1:30 PM

Location: Room 255

Zine-Eddine Khene*, Rennes, France, Axel Bex, London, United Kingdom, Karim Bensalah, Rennes, France

- ZK

Podium Presenter(s)

Introduction: Keynote 564 was a double-blind randomised phase 3 trial comparing adjuvant pembrolizumab versus placebo for up to one year in patients who had a completely resected ccRCC considered at high risk of recurrence. The interim analysis has sparked enthusiasm in the onco-urological community since the primary endpoint (investigator assessed disease free survival (DFS)) was reached. However, In the Keynote-564 trial, inclusion criteria were very heterogeneous. The trial included patients who were considered at “intermediate-high risk” (pT2 and G4 or sarcomatoid, pT3) and “high risk” (pT4, N1) of recurrence. Our objective was to investigate the real risk associated with these prognostic groups in a cohort of patients treated in a “real life” setting outside of a clinical trial.

Methods: Patients who underwent radical or partial nephrectomy for a localized ccRCC between 2010 and 2020 were analyzed. We exclusively focused on patients with pT2 and G4 or sarcomatoid, pT3, pT4 and N1 (i.e., whose characteristics matched Keynote 564 prognostic classification). We excluded patients who received adjuvant or neo-adjuvant treatment. we plotted the survival curves using the Kaplan Meier estimates to make a direct visual comparison between groups.

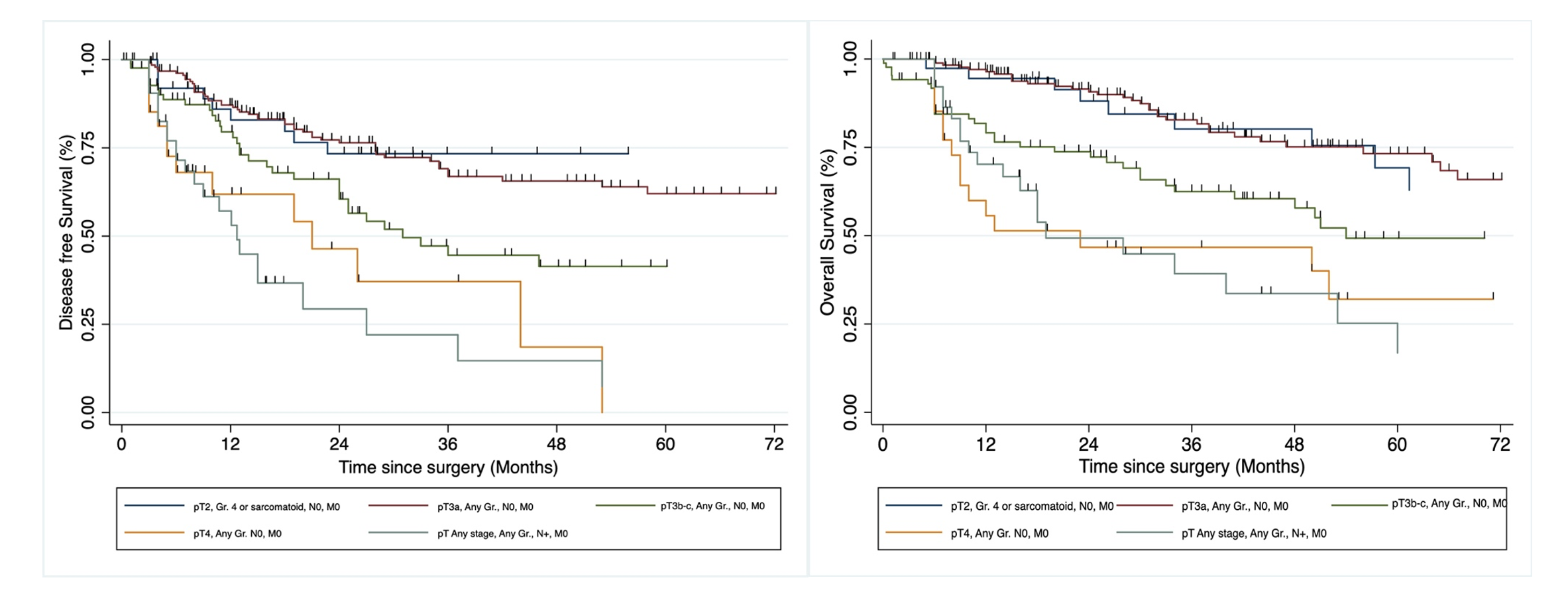

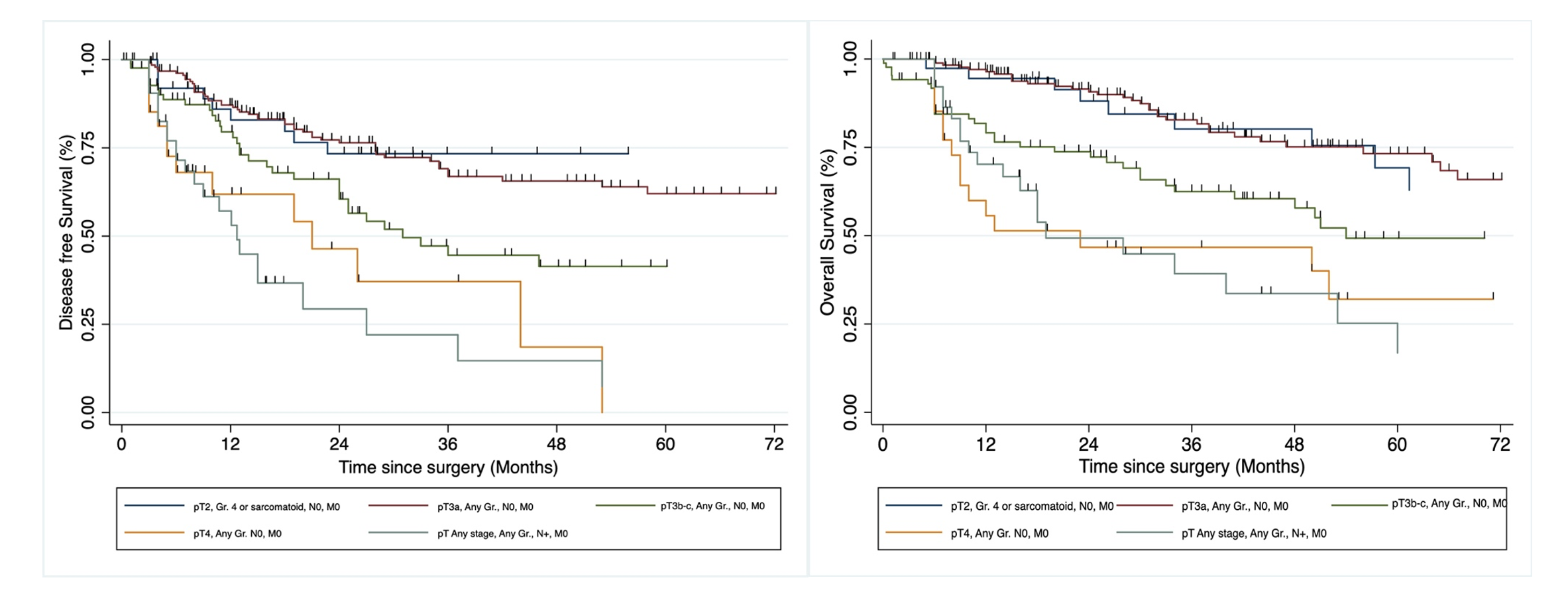

Results: 400 patients were included in the analysis. Kaplan-Meier curves for DFS (A) and OS (B) according to Keynote-564 inclusion criteria are clearly separating (figure 1). Patients with the best outcome are those with pT2 and pT3a tumours, whereas pT3b-c, pT4 and N1 patients have a far worse prognosis. Following this observation, we conducted an exploratory analysis by dividing our cohort into two prognostic groups: 1) pT2 and G4 or sarcomatoid, pT3a N0 and 2) pT3b-c, pT4 and N1 and found a very significant difference (p < 0.05).

Conclusions: The patients included in Keynote 564 have heterogenous disease stages that will exhibit different natural histories. It is therefore questionable to consider them all equally eligible for an adjuvant treatment. Moreover, including patients with a good prognosis in the trial and thus the primary analysis may obscure the benefit of adjuvant therapy for patients with a poor prognosis.

Source of Funding: None

Methods: Patients who underwent radical or partial nephrectomy for a localized ccRCC between 2010 and 2020 were analyzed. We exclusively focused on patients with pT2 and G4 or sarcomatoid, pT3, pT4 and N1 (i.e., whose characteristics matched Keynote 564 prognostic classification). We excluded patients who received adjuvant or neo-adjuvant treatment. we plotted the survival curves using the Kaplan Meier estimates to make a direct visual comparison between groups.

Results: 400 patients were included in the analysis. Kaplan-Meier curves for DFS (A) and OS (B) according to Keynote-564 inclusion criteria are clearly separating (figure 1). Patients with the best outcome are those with pT2 and pT3a tumours, whereas pT3b-c, pT4 and N1 patients have a far worse prognosis. Following this observation, we conducted an exploratory analysis by dividing our cohort into two prognostic groups: 1) pT2 and G4 or sarcomatoid, pT3a N0 and 2) pT3b-c, pT4 and N1 and found a very significant difference (p < 0.05).

Conclusions: The patients included in Keynote 564 have heterogenous disease stages that will exhibit different natural histories. It is therefore questionable to consider them all equally eligible for an adjuvant treatment. Moreover, including patients with a good prognosis in the trial and thus the primary analysis may obscure the benefit of adjuvant therapy for patients with a poor prognosis.

Source of Funding: None

.jpg)

.jpg)