Back

Poster, Podium & Video Sessions

Best Poster Award

MP31: Health Services Research: Quality Improvement & Patient Safety II

MP31-12: High Levels of Hidden Segregation Exist for Black and White Patients Undergoing Cancer Surgery within the Same Hospital

Saturday, May 14, 2022

2:45 PM – 4:00 PM

Location: Room 228

Lillian Lai*, Addison Shay, Sitara Murali, Phyllis Yan, John Hollingsworth, Ann Arbor, MI

Lillian Y. Lai, MD,MS

University of Michigan

Poster Presenter(s)

Introduction: Black patients are significantly more likely to suffer complications following surgery than their white counterparts, even when treated at the same facility. But why would racial disparities in surgical outcomes exist within a hospital? Emerging data from the cardiac surgery literature suggest one possibility: Black and white patients appear to be systematically cared for by different teams of physicians around their operation. To examine whether such hidden segregation exists for patients undergoing major cancer surgery, we analyzed national Medicare data.

Methods: We identified Black and white Medicare beneficiaries with cancer who underwent cystectomy, colectomy, pancreatectomy, or lung resection between 2010 and 2018. After determining all physicians involved in each patient’s surgical episode (index hospitalization to 90 days post discharge), we aggregated across episodes at a given hospital to construct the procedure-specific team of physicians. To measure hidden segregation, we calculated the hospital’s dissimilarity index. This index, ranging from 0-1, captures the extent to which physicians who treated Black patients overlapped with those who treated white patients. When it equals 1, physicians at the hospital treated only Black or only white patients. We fit multivariable regression models to determine factors associated with treatment at a high segregation hospital.

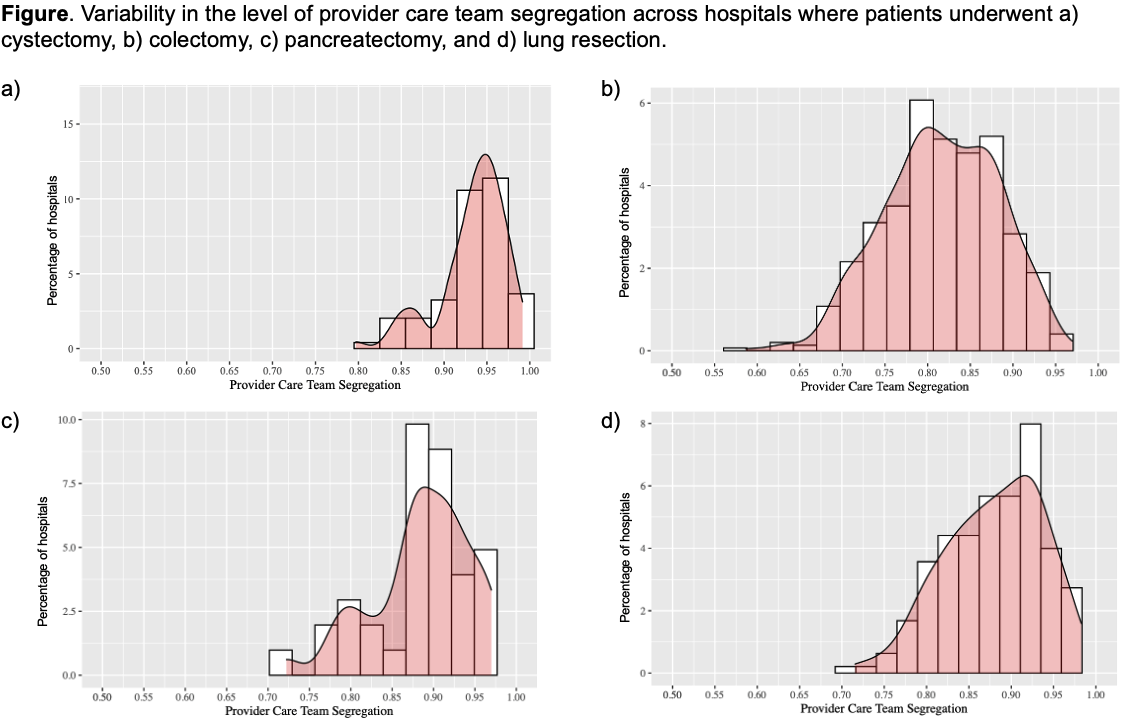

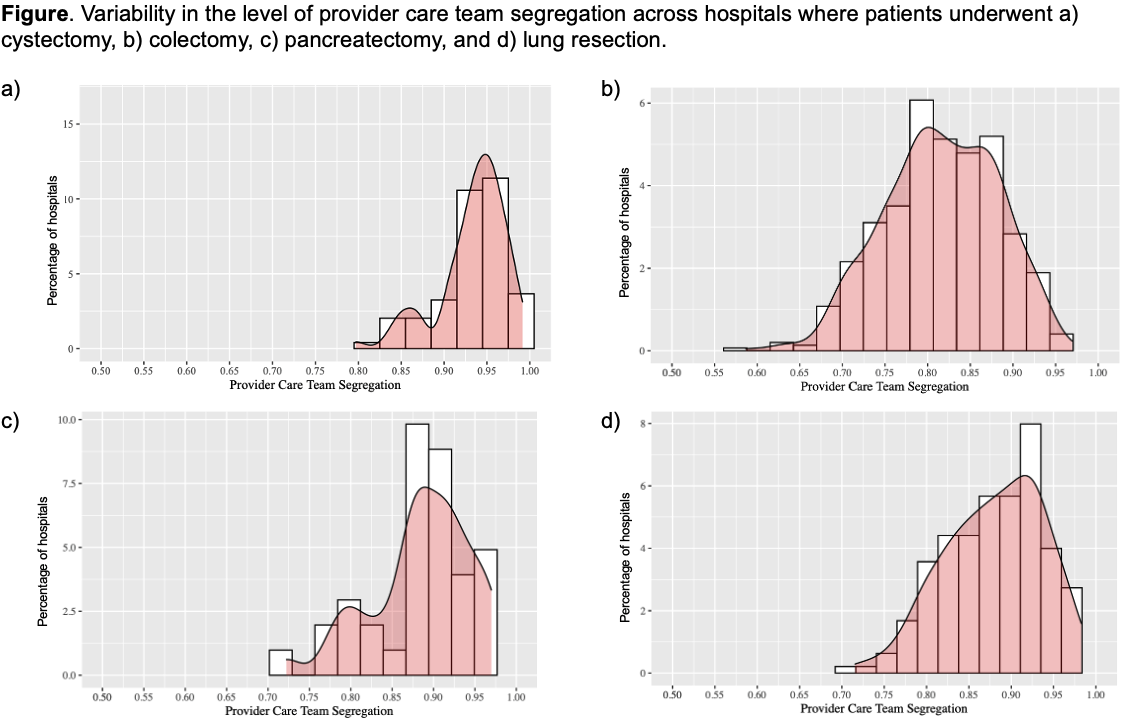

Results: The median level of hidden segregation was high for all procedures (cystectomy 0.94; colectomy 0.82; pancreatectomy 0.89; lung resection 0.89) but varied across hospitals (Figure). On multivariable regression, with the exception of cystectomy, Black patients had lower odds than white patients to be treated at a hospital with high hidden segregation (colectomy OR 0.44 [95%CI 0.36 to 0.53]; pancreatectomy OR 0.55 [95% CI 0.31 to 0.98]; lung resection OR 0.40 [95%CI 0.33 to 0.50]). Consistent across all procedures, medium and high socioeconomic status were associated with higher odds of treatment at a hospital with high hidden segregation.

Conclusions: There exist high levels of hidden segregation for Black and white patients undergoing major cancer surgery within the same hospital. This finding helps shed light on persistent racial disparities in surgical outcomes.

Source of Funding: NCI T32 CA180984 for LYL

Methods: We identified Black and white Medicare beneficiaries with cancer who underwent cystectomy, colectomy, pancreatectomy, or lung resection between 2010 and 2018. After determining all physicians involved in each patient’s surgical episode (index hospitalization to 90 days post discharge), we aggregated across episodes at a given hospital to construct the procedure-specific team of physicians. To measure hidden segregation, we calculated the hospital’s dissimilarity index. This index, ranging from 0-1, captures the extent to which physicians who treated Black patients overlapped with those who treated white patients. When it equals 1, physicians at the hospital treated only Black or only white patients. We fit multivariable regression models to determine factors associated with treatment at a high segregation hospital.

Results: The median level of hidden segregation was high for all procedures (cystectomy 0.94; colectomy 0.82; pancreatectomy 0.89; lung resection 0.89) but varied across hospitals (Figure). On multivariable regression, with the exception of cystectomy, Black patients had lower odds than white patients to be treated at a hospital with high hidden segregation (colectomy OR 0.44 [95%CI 0.36 to 0.53]; pancreatectomy OR 0.55 [95% CI 0.31 to 0.98]; lung resection OR 0.40 [95%CI 0.33 to 0.50]). Consistent across all procedures, medium and high socioeconomic status were associated with higher odds of treatment at a hospital with high hidden segregation.

Conclusions: There exist high levels of hidden segregation for Black and white patients undergoing major cancer surgery within the same hospital. This finding helps shed light on persistent racial disparities in surgical outcomes.

Source of Funding: NCI T32 CA180984 for LYL

.jpg)

.jpg)