Back

Poster, Podium & Video Sessions

Podium

PD29: Trauma/Reconstruction/Diversion: External Genitalia Reconstruction and Urotrauma (including transgender surgery) II

PD29-04: Comparison of Stricture Characteristics and Urethroplasty Success Rates Caused by External versus Internal Urethral Trauma

Saturday, May 14, 2022

1:30 PM – 1:40 PM

Location: Room 244

Faizan Khawaja*, Kevin Flynn, Iowa City, IA, Shawn Grove, Minneapolis, MN, Nejd Alsikafi, Gurnee, IL, Joshua Broghammer, Kansas City, KS, Jill Buckley, San Diego, CA, Sean Elliott, Minneapolis, MN, Jeremy Myers, Salt Lake City, UT, Andrew Peterson, Durham , NC, Keith Rourke, Edmonton , Canada, Thomas Smith III, Houston, TX, Alex Vanni, Burlington, MA, Lee Zhao, New York City, NY, Bradley Erickson, Iowa City, IA

- FK

Podium Presenter(s)

Introduction: Trauma is a commonly listed etiology for anterior urethral stricture disease (aUSD). Trauma can be the result of external (e.g. straddle injury) or internal trauma (e.g. TURP injury). Herein we compare the differences in stricture and urethroplasty characteristics between the two, hypothesizing that the differences in stricture development mechanism will portend different surgical outcomes.

Methods: The Trauma and Urologic Reconstruction Network of Surgeons (TURNS) prospective database was used to develop a cohort of external urethral trauma (E1) and internal urethral trauma (E3a) aUSD. Stricture and repair variables were compared between cohorts using descriptive statistics. Longitudinal outcomes were compared using Kaplan Meier time to event analysis.

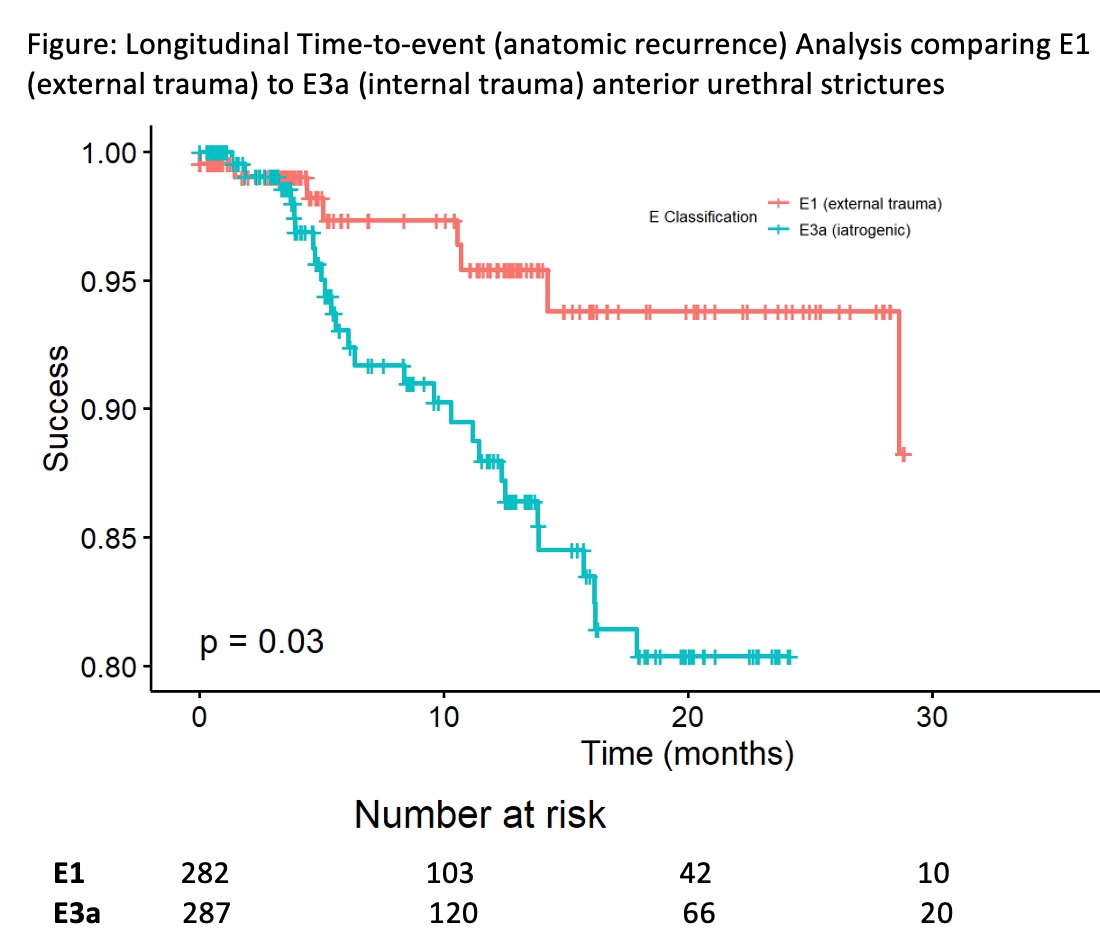

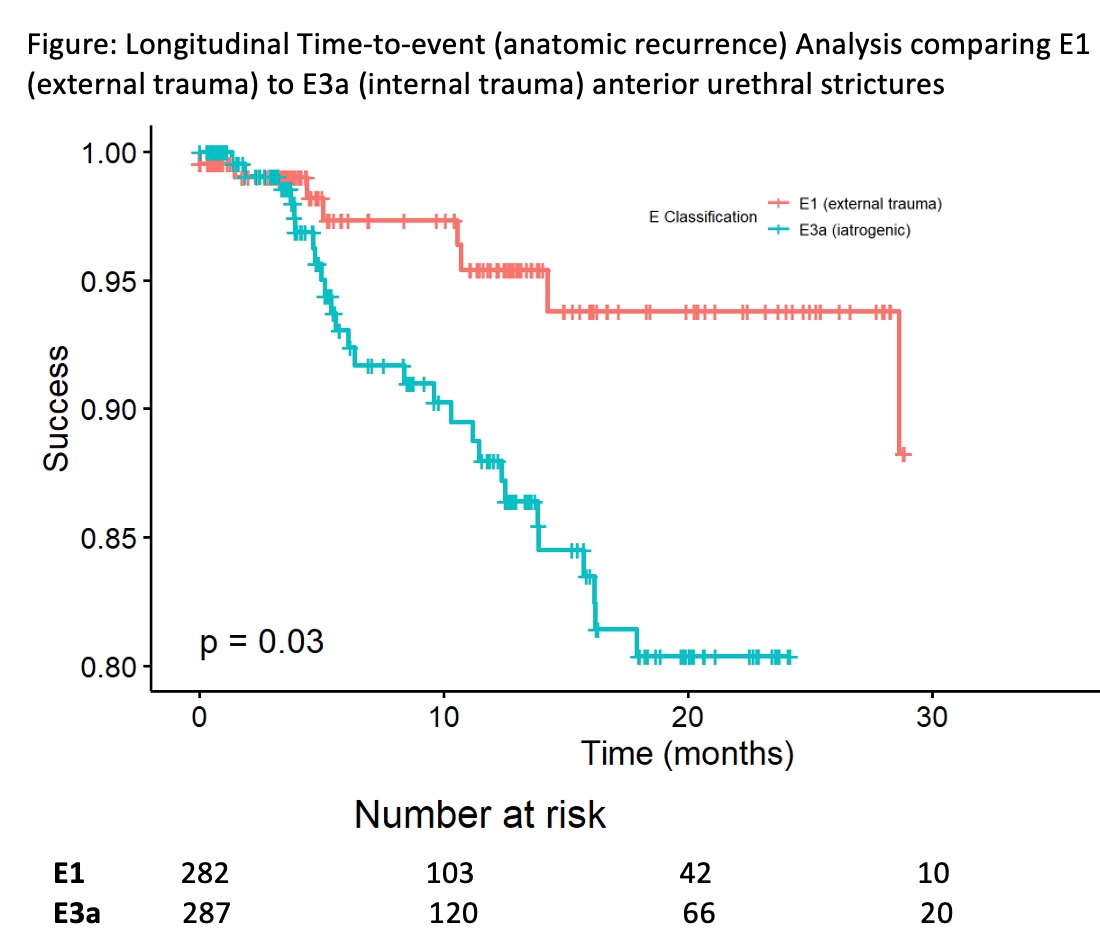

Results: Of the 2137 aUSD in the TURNS database, 282 (13.2%) were E1 and 287 (13.4%) were E3a. Mean stricture lengths between E1 (3.1 ± 2.6) and E3a (3.9 ± 3.1) differed significantly (p <0.001). The vast majority of E1 strictures were located in the bulbar urethra (89%; Proximal bulb (S1a), 73%; Distal bulb (S1b), 16%) versus only 52% of S3a strictures (37% S1a; 16% S1b) (p < 0.001). The overall urethroplasty success rate for E1 strictures was 84% varying significantly by location (S1a 89% v. Penoscrotal (S2a) 60%; p < 0.001), the majority being amenable to excisional repairs (51%). This differed significantly from E3a (p < 0.001) urethroplasty success (overall 77%; S1a 78% v. S2a 71%; p < 0.001), the majority requiring substitutional repairs (75%). The Figure reveals significant early separation of urethroplasty success over time (p = 0.03) with a median time to failure for E3a strictures being < 6 months.

Conclusions: Traumatic strictures are common, constituting over 25% of all aUSD in the TURNS urethroplasty database. However, the mechanism of injury, whether from external trauma (which generally results in a well-defined area of disease) versus internal trauma (which is often the result of ischemia with disease extent that is less certain/defined) leads to different stricture locations and lengths, thereby significantly affecting surgical outcomes. The ischemic nature of strictures from internal trauma, and early failure rates, should alert surgeons to the possibility of disease extending beyond the visible stricture, and of an unreliable local blood supply when supporting grafts.

Source of Funding: NIDDK 1R21DK115945-01

Methods: The Trauma and Urologic Reconstruction Network of Surgeons (TURNS) prospective database was used to develop a cohort of external urethral trauma (E1) and internal urethral trauma (E3a) aUSD. Stricture and repair variables were compared between cohorts using descriptive statistics. Longitudinal outcomes were compared using Kaplan Meier time to event analysis.

Results: Of the 2137 aUSD in the TURNS database, 282 (13.2%) were E1 and 287 (13.4%) were E3a. Mean stricture lengths between E1 (3.1 ± 2.6) and E3a (3.9 ± 3.1) differed significantly (p <0.001). The vast majority of E1 strictures were located in the bulbar urethra (89%; Proximal bulb (S1a), 73%; Distal bulb (S1b), 16%) versus only 52% of S3a strictures (37% S1a; 16% S1b) (p < 0.001). The overall urethroplasty success rate for E1 strictures was 84% varying significantly by location (S1a 89% v. Penoscrotal (S2a) 60%; p < 0.001), the majority being amenable to excisional repairs (51%). This differed significantly from E3a (p < 0.001) urethroplasty success (overall 77%; S1a 78% v. S2a 71%; p < 0.001), the majority requiring substitutional repairs (75%). The Figure reveals significant early separation of urethroplasty success over time (p = 0.03) with a median time to failure for E3a strictures being < 6 months.

Conclusions: Traumatic strictures are common, constituting over 25% of all aUSD in the TURNS urethroplasty database. However, the mechanism of injury, whether from external trauma (which generally results in a well-defined area of disease) versus internal trauma (which is often the result of ischemia with disease extent that is less certain/defined) leads to different stricture locations and lengths, thereby significantly affecting surgical outcomes. The ischemic nature of strictures from internal trauma, and early failure rates, should alert surgeons to the possibility of disease extending beyond the visible stricture, and of an unreliable local blood supply when supporting grafts.

Source of Funding: NIDDK 1R21DK115945-01

.jpg)

.jpg)