Back

Poster Session D

Crystal arthropathies

Session: (1787–1829) Metabolic and Crystal Arthropathies – Basic and Clinical Science Poster

1810: Frequency and Patterns of Opioid Use in the Management of Gout: A Population-Based Study

Monday, November 14, 2022

1:00 PM – 3:00 PM Eastern Time

Location: Virtual Poster Hall

- TN

Tuhina Neogi, MD, PhD

Boston University School of Medicine

Brookline, MA, United States

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Tuhina Neogi1, Martin Englund2, Aleksandra Turkiewicz2 and Ali Kiadaliri2, 1Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, 2Lund University, Lund, Sweden

Background/Purpose: Treatment guidelines for management of gout do not recommend opioids. We evaluated the frequency of opioid prescriptions in those with gout compared with the general population, and evaluated frequency of use of other recommended gout medications

Methods: We used population-based register data from the Skåne region of Sweden to identify adults aged ≥18 years as of Dec 31, 2009 residing in Skåne between 1998-2009 and without a gout diagnosis but at last one in-person healthcare contact during this time. Among this cohort, we identified people with incident gout (date of diagnosis was the index date) using ICD-10 codes between 2010- 2018, and used risk set sampling to age- and sex-match those with gout to those without gout in a 1:5 ratio. We excluded individuals who had a cancer diagnosis in the 5-year period or an opioid prescription in the 2-year period prior to the index date. We evaluated the cumulative incidence, and risk ratio (RR) of new opioid prescriptions within the first year following incident gout diagnosis (index date) among those with gout compared with those without gout, and evaluated the population attributable fraction of opioid prescriptions related to incident gout diagnosis. The regression models were adjusted for potential confounders (see Figures). Among those with gout, we evaluated the RR of recommended gout medications prescribed in the first year after incident gout diagnosis.

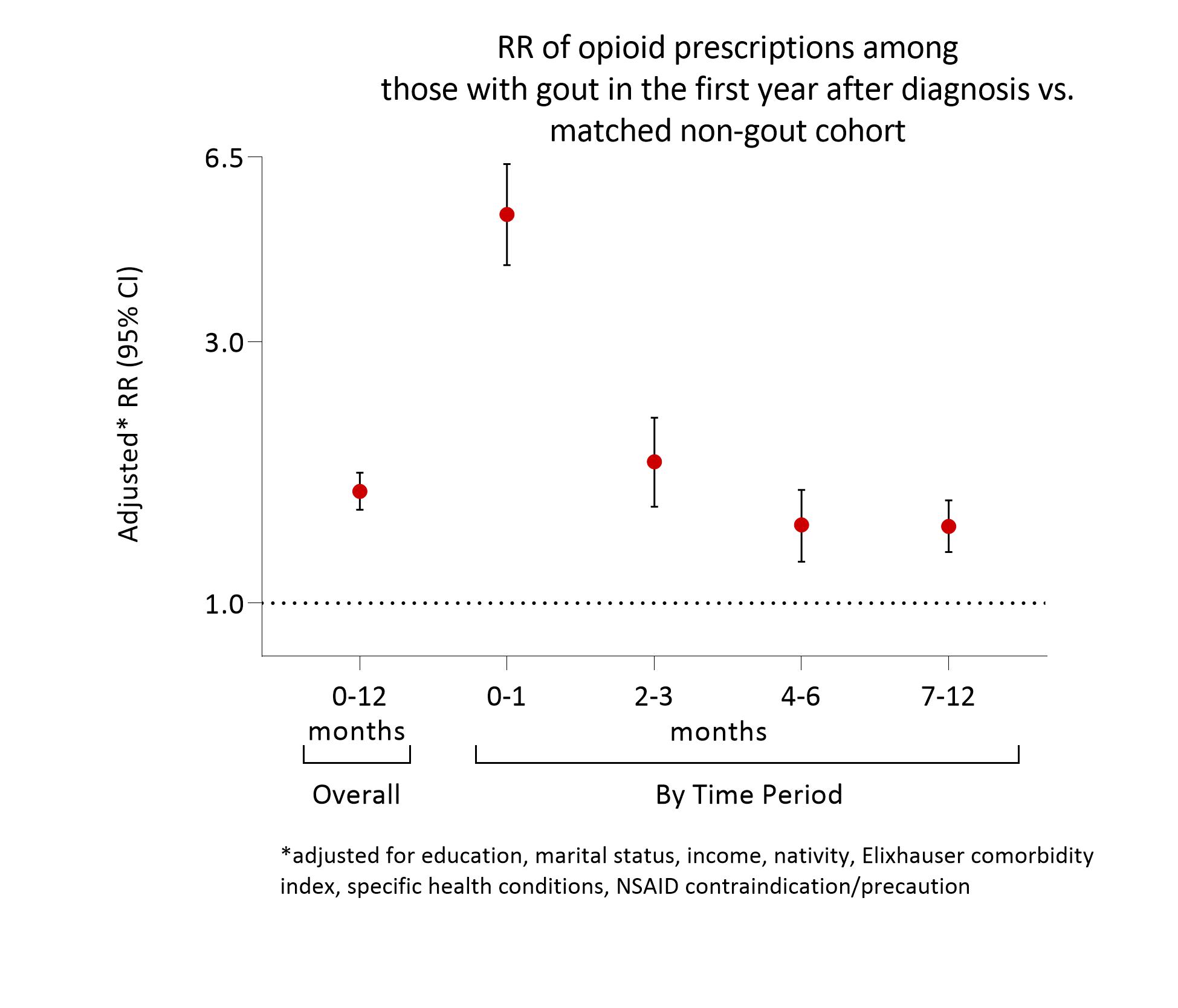

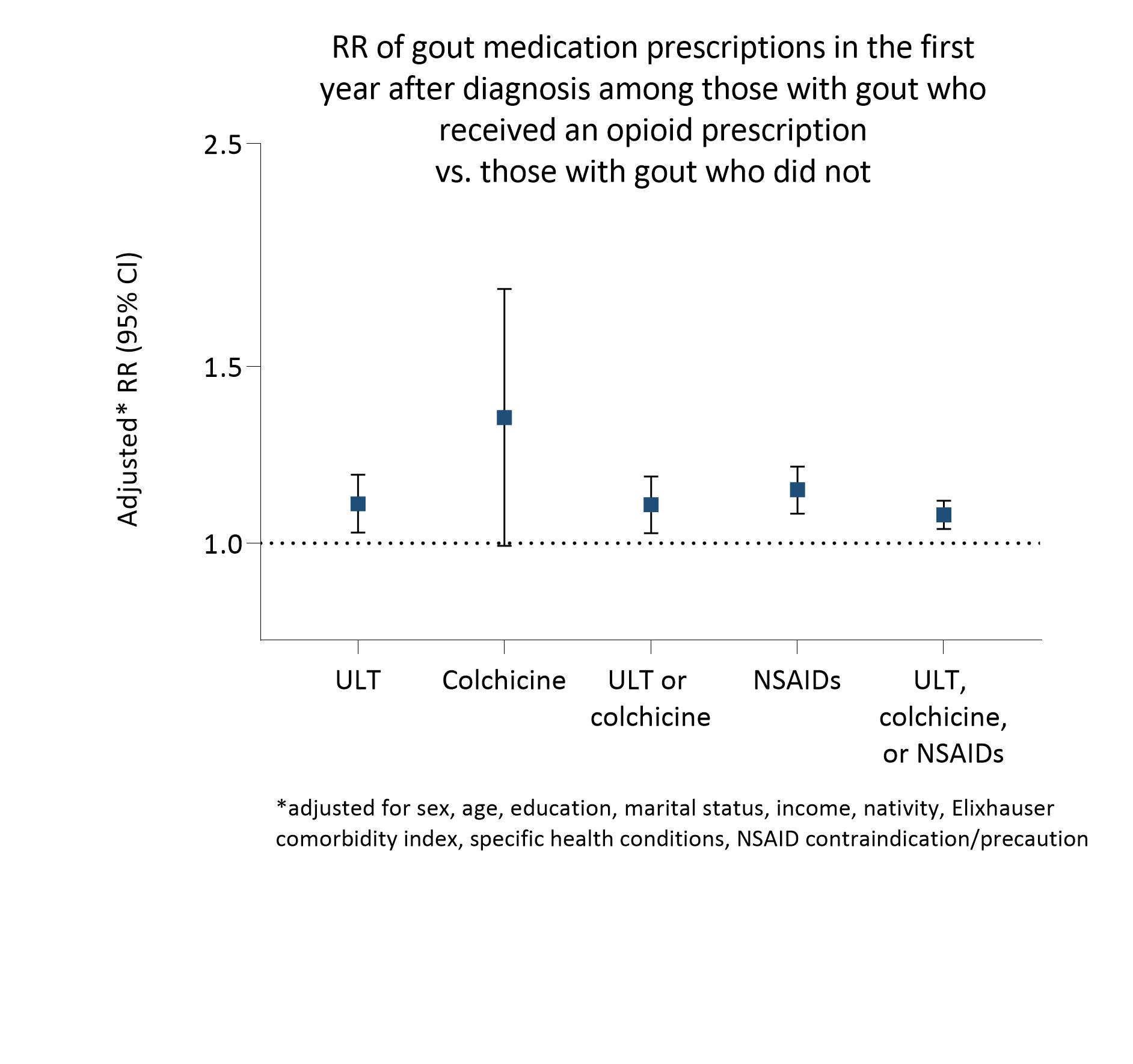

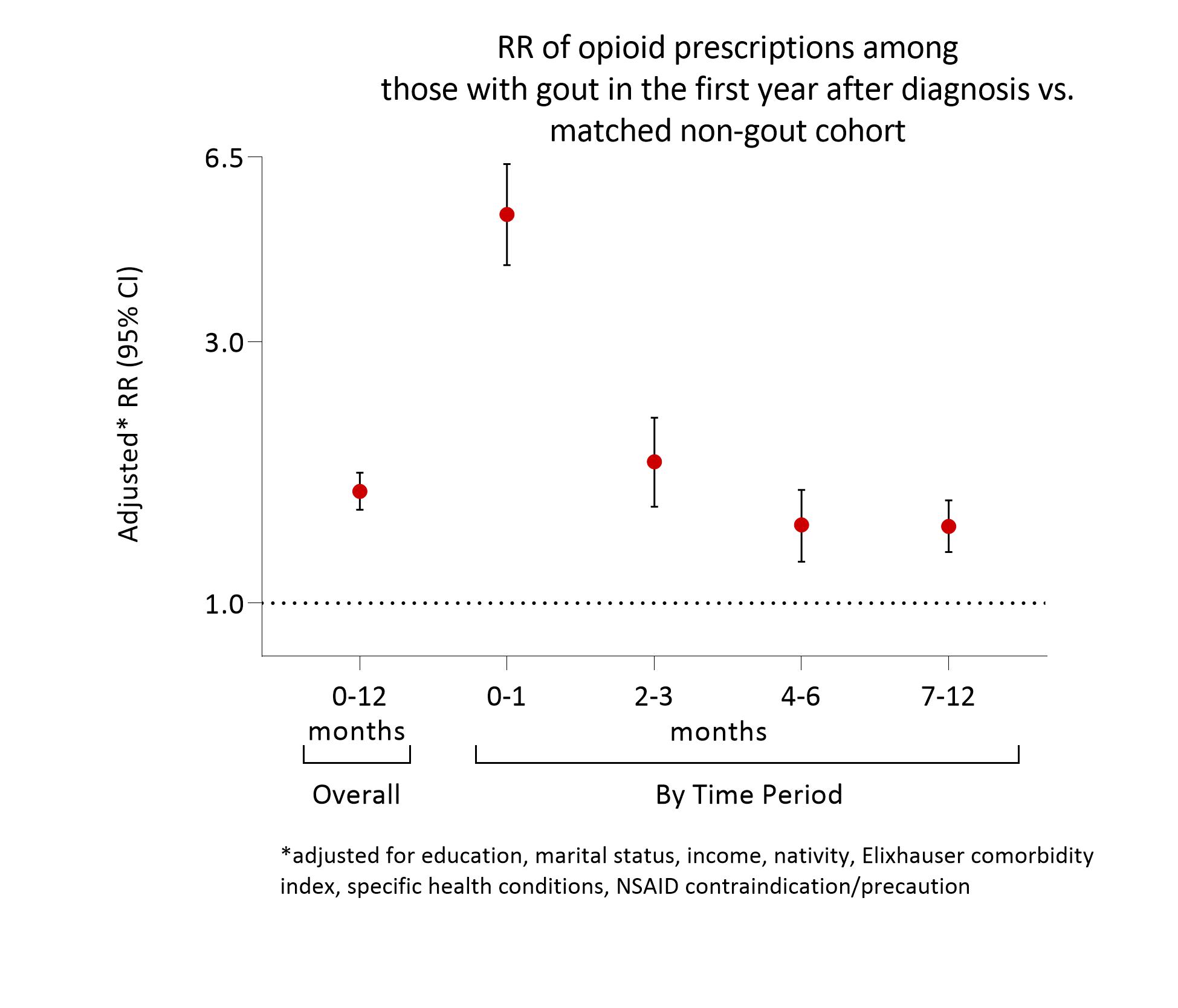

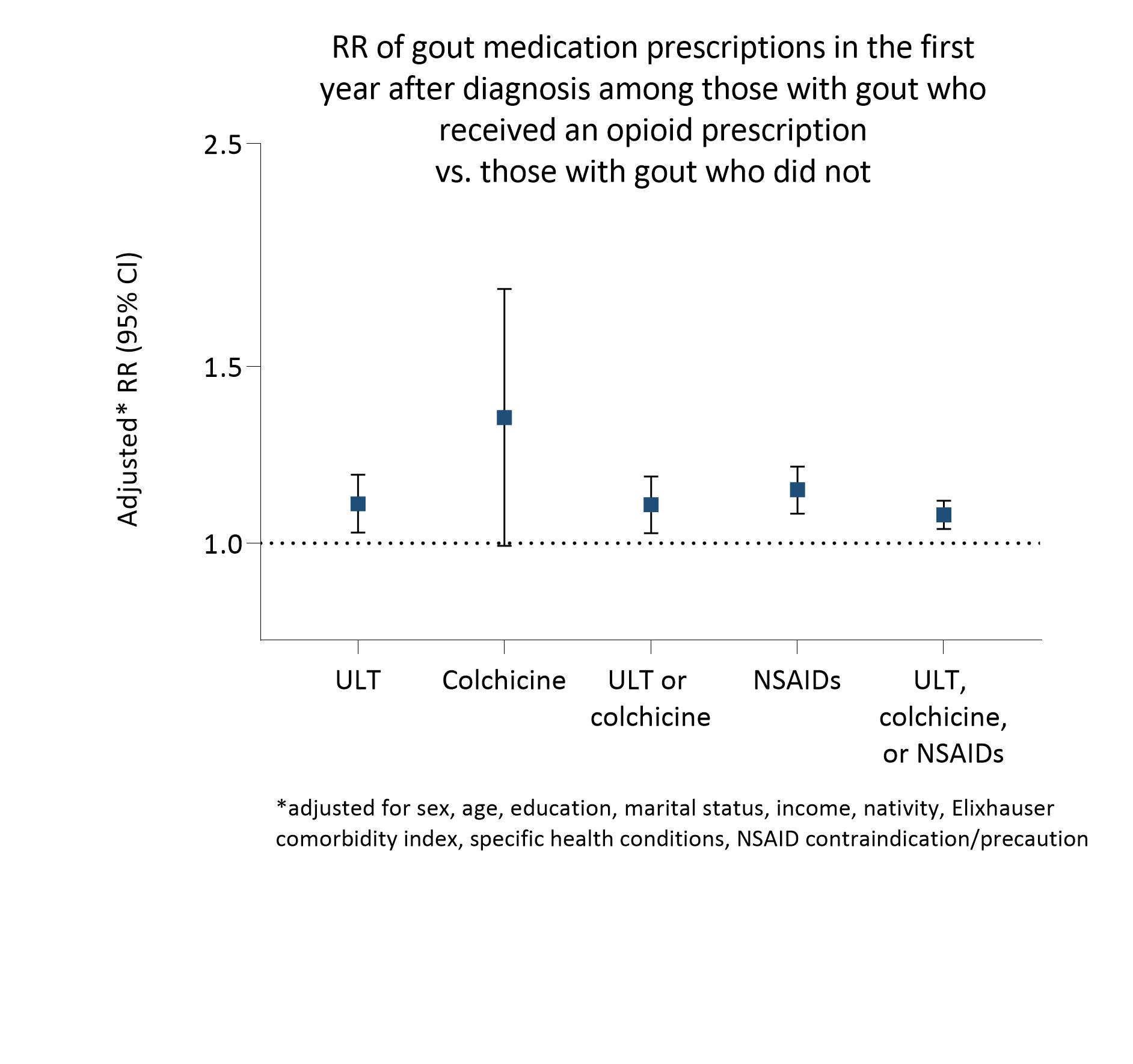

Results: We identified 8,293 with incident gout (mean age 65.4, 24.4% women), who were matched to 28,576 comparators without gout (mean age 67.1, 26.6% women). Among those with gout, 13.1% received an opioid prescription during the first year post-index date, while the corresponding frequency was 6.6% in the comparator group (cumulative incidence shown in Figure 1). Of those who received an opioid prescription, codeine combinations (42% in gout; 33% in non-gout), tramadol (18%, 16%), and morphine (12.5%, 15.5%) were the most common opioids prescribed. The highest incidence rate of opioid prescriptions occurred within the first month of incident gout diagnosis compared with the non-gout group, though remained elevated throughout the first year (Figure 2). The population-attributable fraction of opioid prescription related to gout was 15.1% (95% CI 13.1-17.2). Among those with gout, the RR of urate-lowering therapy and other gout flare prescriptions within the first year post-index date was slightly higher among those who had received an opioid prescription than those who did not receive one (Figure 3).

Conclusion: Opioid prescriptions are common within the first year after a gout diagnosis, being at least double compared with the general population without gout, and particularly high in the first month. However, use of recommended gout medications was similar or higher among those who had received an opioid prescription within the first year of gout diagnosis. This suggests that opioids may be prescribed due to lack of adequate effective flare management options.

.jpg) Figure 1: Cumulative incidence of opioid prescription in first year after gout diagnosis, compared with matched non-gout cohort

Figure 1: Cumulative incidence of opioid prescription in first year after gout diagnosis, compared with matched non-gout cohort

Risk Ratios of opioid prescription among those with gout in the first year after diagnosis compared with a matched non-gout cohort

Risk Ratios of opioid prescription among those with gout in the first year after diagnosis compared with a matched non-gout cohort

Risk Ratios of gout-related medications prescribed in the first year after diagnosis among those with gout who received an opioid prescription(s) vs. those with gout who did not

Risk Ratios of gout-related medications prescribed in the first year after diagnosis among those with gout who received an opioid prescription(s) vs. those with gout who did not

Disclosures: T. Neogi, Novartis, Pfizer/Lilly, Regeneron; M. Englund, None; A. Turkiewicz, None; A. Kiadaliri, Joint Academy®.

Background/Purpose: Treatment guidelines for management of gout do not recommend opioids. We evaluated the frequency of opioid prescriptions in those with gout compared with the general population, and evaluated frequency of use of other recommended gout medications

Methods: We used population-based register data from the Skåne region of Sweden to identify adults aged ≥18 years as of Dec 31, 2009 residing in Skåne between 1998-2009 and without a gout diagnosis but at last one in-person healthcare contact during this time. Among this cohort, we identified people with incident gout (date of diagnosis was the index date) using ICD-10 codes between 2010- 2018, and used risk set sampling to age- and sex-match those with gout to those without gout in a 1:5 ratio. We excluded individuals who had a cancer diagnosis in the 5-year period or an opioid prescription in the 2-year period prior to the index date. We evaluated the cumulative incidence, and risk ratio (RR) of new opioid prescriptions within the first year following incident gout diagnosis (index date) among those with gout compared with those without gout, and evaluated the population attributable fraction of opioid prescriptions related to incident gout diagnosis. The regression models were adjusted for potential confounders (see Figures). Among those with gout, we evaluated the RR of recommended gout medications prescribed in the first year after incident gout diagnosis.

Results: We identified 8,293 with incident gout (mean age 65.4, 24.4% women), who were matched to 28,576 comparators without gout (mean age 67.1, 26.6% women). Among those with gout, 13.1% received an opioid prescription during the first year post-index date, while the corresponding frequency was 6.6% in the comparator group (cumulative incidence shown in Figure 1). Of those who received an opioid prescription, codeine combinations (42% in gout; 33% in non-gout), tramadol (18%, 16%), and morphine (12.5%, 15.5%) were the most common opioids prescribed. The highest incidence rate of opioid prescriptions occurred within the first month of incident gout diagnosis compared with the non-gout group, though remained elevated throughout the first year (Figure 2). The population-attributable fraction of opioid prescription related to gout was 15.1% (95% CI 13.1-17.2). Among those with gout, the RR of urate-lowering therapy and other gout flare prescriptions within the first year post-index date was slightly higher among those who had received an opioid prescription than those who did not receive one (Figure 3).

Conclusion: Opioid prescriptions are common within the first year after a gout diagnosis, being at least double compared with the general population without gout, and particularly high in the first month. However, use of recommended gout medications was similar or higher among those who had received an opioid prescription within the first year of gout diagnosis. This suggests that opioids may be prescribed due to lack of adequate effective flare management options.

.jpg) Figure 1: Cumulative incidence of opioid prescription in first year after gout diagnosis, compared with matched non-gout cohort

Figure 1: Cumulative incidence of opioid prescription in first year after gout diagnosis, compared with matched non-gout cohort Risk Ratios of opioid prescription among those with gout in the first year after diagnosis compared with a matched non-gout cohort

Risk Ratios of opioid prescription among those with gout in the first year after diagnosis compared with a matched non-gout cohort Risk Ratios of gout-related medications prescribed in the first year after diagnosis among those with gout who received an opioid prescription(s) vs. those with gout who did not

Risk Ratios of gout-related medications prescribed in the first year after diagnosis among those with gout who received an opioid prescription(s) vs. those with gout who did notDisclosures: T. Neogi, Novartis, Pfizer/Lilly, Regeneron; M. Englund, None; A. Turkiewicz, None; A. Kiadaliri, Joint Academy®.