Back

Poster Session D

Epidemiology, health policy and outcomes

Session: (1750–1786) Epidemiology and Public Health Poster III

1755: Improving Quality of Life Through Connection: A Scoping Review of Peer Coaching Interventions in the Field of Rheumatology

Monday, November 14, 2022

1:00 PM – 3:00 PM Eastern Time

Location: Virtual Poster Hall

- MC

Megan Creasman, MD

NYP-Weill Cornell

New York, NY, United States

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Megan Creasman1, Mackenzie Brown2, Yuliana Domínguez Páez3, Michelle Demetres4, Monika Safford4 and Iris Navarro-Millan4, 1NYP-Weill Cornell, New York, NY, 2Weill Cornell Medicine, Brooklyn, NY, 3Weill Cornell Medicine, Bronx, NY, 4Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, NY

Background/Purpose: Peer coaches are lay individuals providing health education and behavior change interventions, and often have the same condition as the person that they are coaching. Peer coaching is a promising tool for patients with rheumatic musculoskeletal diseases (RMD) to improve self-care strategies and health outcomes. This scoping review aims to describe and compare the characteristics of existing interventions utilizing peer coaching for adults with RMD.

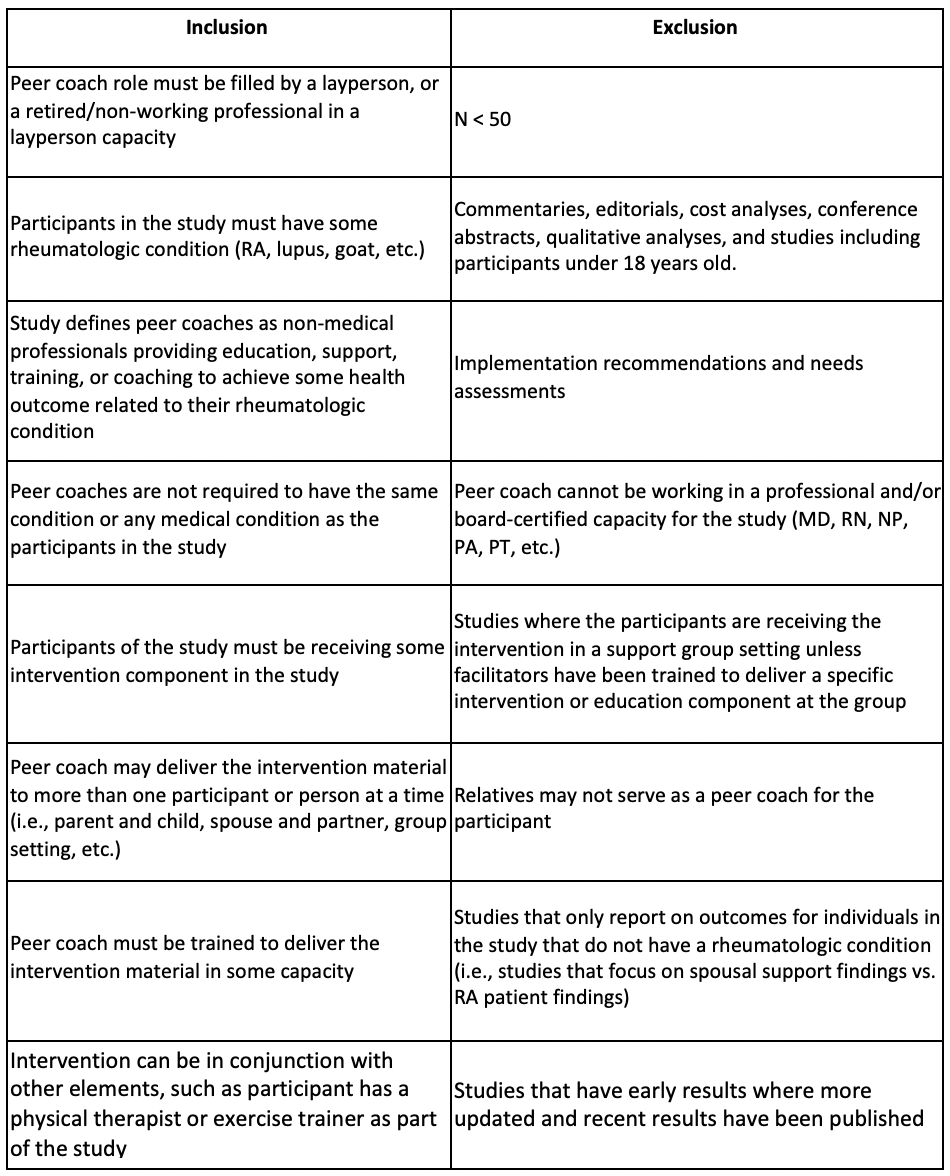

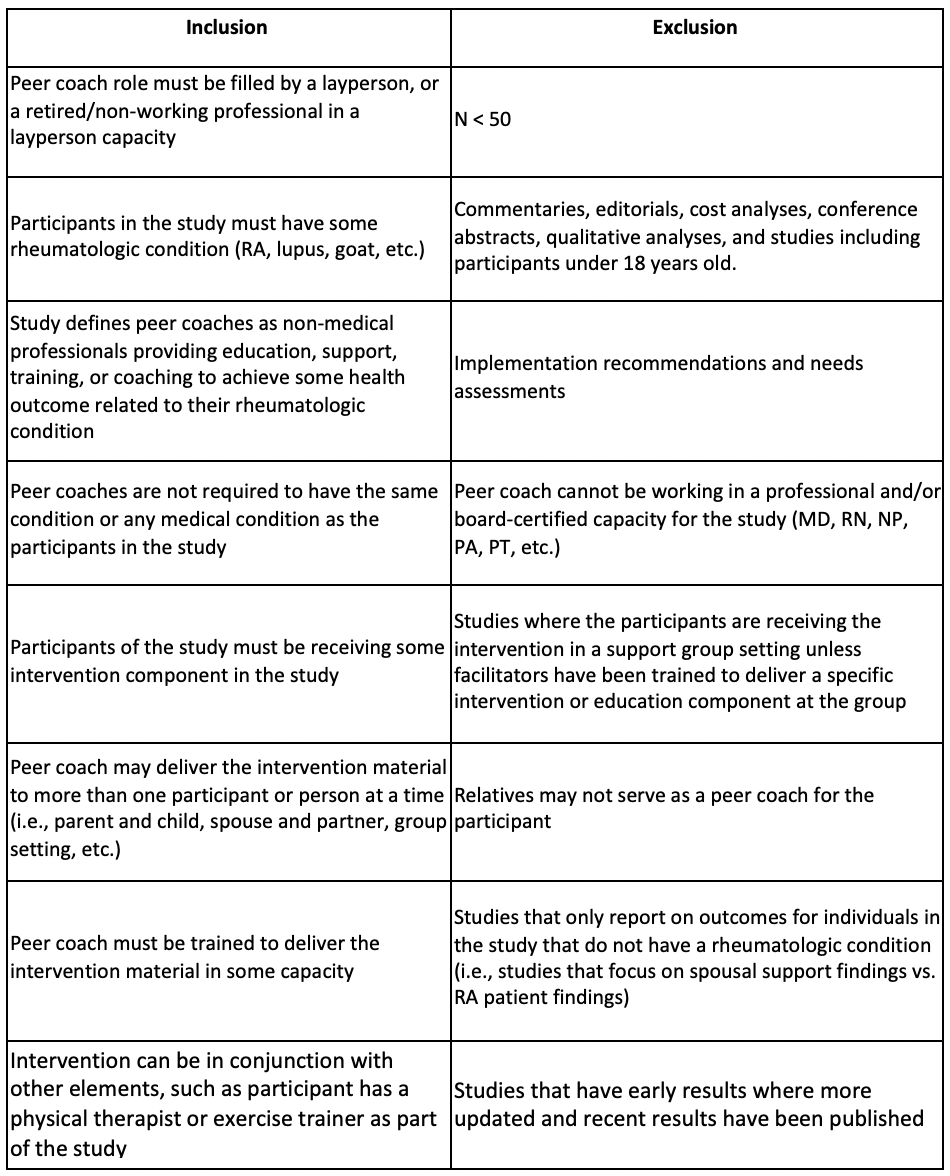

Methods: A literature search was conducted in Ovid MEDLINE and EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and The Cochrane Library in September 2021. Studies retrieved were then screened for eligibility against predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 1).

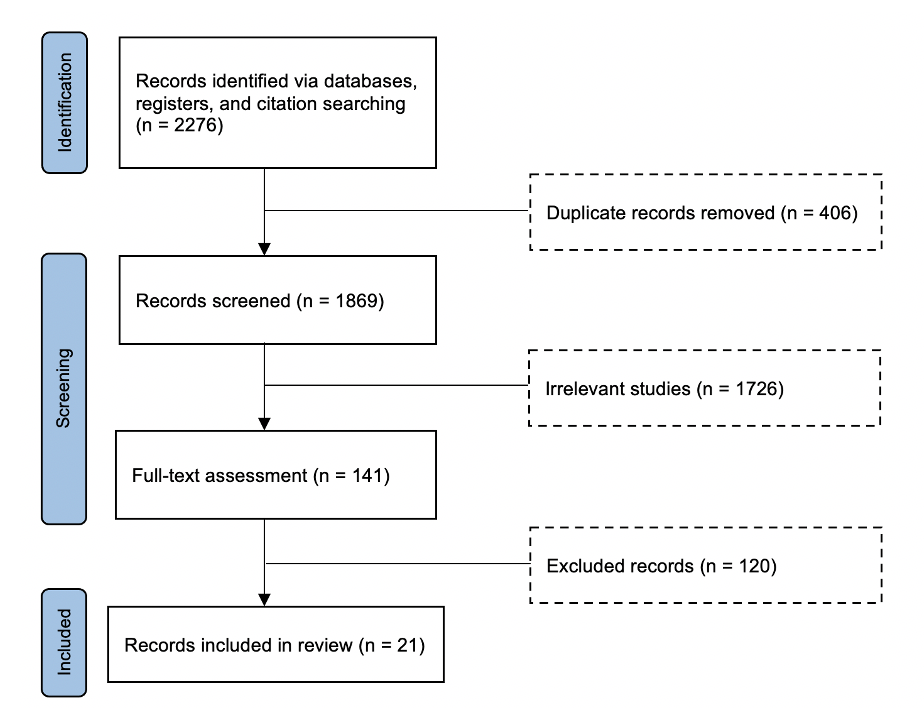

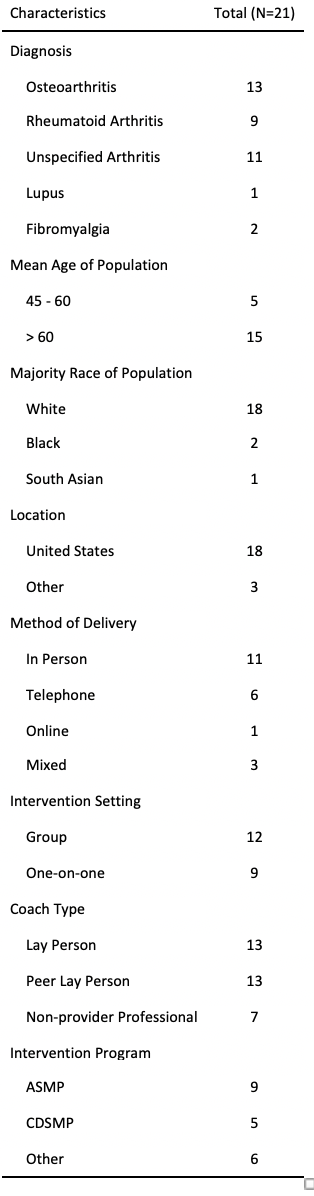

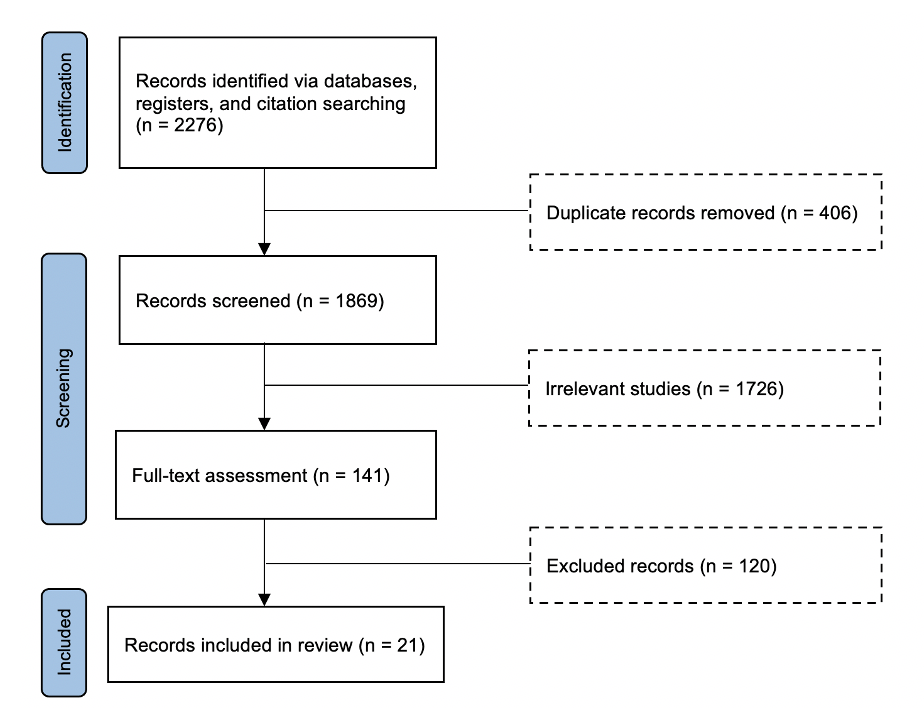

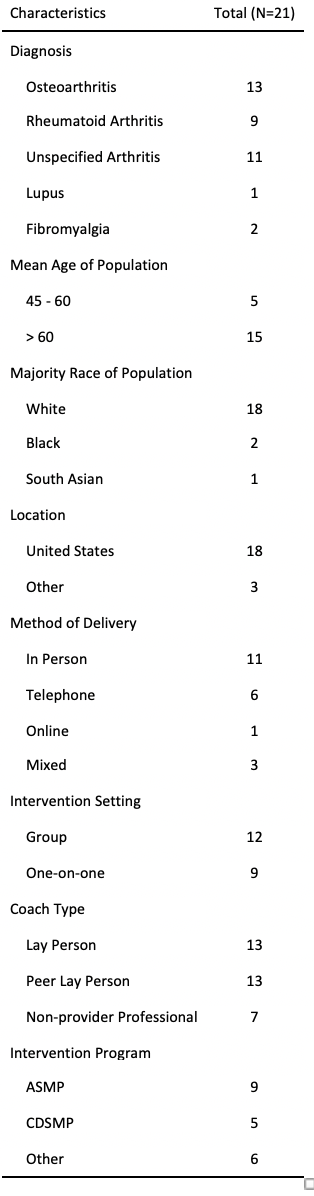

Results: Out of 2,276 articles, 21 were included (Figure 1). Only osteoarthritis (OA) (n=6), only rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (n=2), and both OA and RA (n=7) were the most common RMD studied (Table 2). Studies had a majority White, non-Hispanic or Latino (n=16), female (n=15) population over the age of 60 (n=15), with at least some college education (n=14). Less than 15% of studies (n=3) actively recruited underrepresented groups. Nine of the 21 studies tested the efficacy of the Arthritis Self-Management Program, while 5 tested the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program. The intervention program topics focused on aspects of disease self-management for people with RMD (n=17), rather than healthcare navigation (n=2), information/education (n=2), or medication adherence (n=1). The majority of interventions were delivered in-person (n=11) in a group setting (n=12). Three studies used only lay people diagnosed with the condition of interest to deliver the intervention (peer lay person) (n=3), compared to those that only used laypersons (n=3) or professionals working in a non-provider role (non-provider professional) (n=6). The remaining (n=9) deployed a combination of these coach types. Thirteen studies had predetermined primary outcomes, 2 of which used objective data (ACR criteria improvement and daily step count). Only 8 studies report statistically significant results in the intervention arm versus a comparator, 5 of which defined primary outcomes. These 5 all had more than 100 participants. Only 6 studies had sample sizes over 500 people, 4 of which reported significant findings. The 4 studies that reported significant findings used peer laypersons to deliver some or all of the intervention. Finally, all studies indicated their coaches were trained, but no studies provided replicable training methods.

Conclusion: The majority of these interventions did not show efficacy, which may have been driven in part by small sample sizes and study design challenges, such as lack of theoretical framework, primary outcomes, and active comparators. In addition, the efficacy of even well-designed peer coaching interventions can be limited by poor implementation methodology. The future of peer coaching interventions in the field of rheumatology will depend on having well-designed investigations informed by the principles of behavioral modification and implementation science. Recruitment of diverse populations, as well as of peer leaders with RMD will also be essential.

Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Studies Included in this Review

Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Studies Included in this Review

Figure 1. Flow Diagram for Studies Included in this Review

Figure 1. Flow Diagram for Studies Included in this Review

Table 2. Characteristics of Studies Included in This Review

Table 2. Characteristics of Studies Included in This Review

Disclosures: M. Creasman, None; M. Brown, None; Y. Domínguez Páez, None; M. Demetres, None; M. Safford, None; I. Navarro-Millan, Sweden Orphan Biovitrum (SOBI).

Background/Purpose: Peer coaches are lay individuals providing health education and behavior change interventions, and often have the same condition as the person that they are coaching. Peer coaching is a promising tool for patients with rheumatic musculoskeletal diseases (RMD) to improve self-care strategies and health outcomes. This scoping review aims to describe and compare the characteristics of existing interventions utilizing peer coaching for adults with RMD.

Methods: A literature search was conducted in Ovid MEDLINE and EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and The Cochrane Library in September 2021. Studies retrieved were then screened for eligibility against predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria (Table 1).

Results: Out of 2,276 articles, 21 were included (Figure 1). Only osteoarthritis (OA) (n=6), only rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (n=2), and both OA and RA (n=7) were the most common RMD studied (Table 2). Studies had a majority White, non-Hispanic or Latino (n=16), female (n=15) population over the age of 60 (n=15), with at least some college education (n=14). Less than 15% of studies (n=3) actively recruited underrepresented groups. Nine of the 21 studies tested the efficacy of the Arthritis Self-Management Program, while 5 tested the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program. The intervention program topics focused on aspects of disease self-management for people with RMD (n=17), rather than healthcare navigation (n=2), information/education (n=2), or medication adherence (n=1). The majority of interventions were delivered in-person (n=11) in a group setting (n=12). Three studies used only lay people diagnosed with the condition of interest to deliver the intervention (peer lay person) (n=3), compared to those that only used laypersons (n=3) or professionals working in a non-provider role (non-provider professional) (n=6). The remaining (n=9) deployed a combination of these coach types. Thirteen studies had predetermined primary outcomes, 2 of which used objective data (ACR criteria improvement and daily step count). Only 8 studies report statistically significant results in the intervention arm versus a comparator, 5 of which defined primary outcomes. These 5 all had more than 100 participants. Only 6 studies had sample sizes over 500 people, 4 of which reported significant findings. The 4 studies that reported significant findings used peer laypersons to deliver some or all of the intervention. Finally, all studies indicated their coaches were trained, but no studies provided replicable training methods.

Conclusion: The majority of these interventions did not show efficacy, which may have been driven in part by small sample sizes and study design challenges, such as lack of theoretical framework, primary outcomes, and active comparators. In addition, the efficacy of even well-designed peer coaching interventions can be limited by poor implementation methodology. The future of peer coaching interventions in the field of rheumatology will depend on having well-designed investigations informed by the principles of behavioral modification and implementation science. Recruitment of diverse populations, as well as of peer leaders with RMD will also be essential.

Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Studies Included in this Review

Table 1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Studies Included in this Review Figure 1. Flow Diagram for Studies Included in this Review

Figure 1. Flow Diagram for Studies Included in this Review Table 2. Characteristics of Studies Included in This Review

Table 2. Characteristics of Studies Included in This ReviewDisclosures: M. Creasman, None; M. Brown, None; Y. Domínguez Páez, None; M. Demetres, None; M. Safford, None; I. Navarro-Millan, Sweden Orphan Biovitrum (SOBI).