Back

Poster Session A

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) including psoriatic arthritis (PsA)

Session: (0372–0402) Spondyloarthritis Including PsA – Diagnosis, Manifestations, and Outcomes Poster I

0391: Dynamics of Nail Psoriasis with Guselkumab Treatment and Withdrawal in Association with Skin Response and Patient-reported Outcomes Based on a post Hoc Analysis of Clinical Trial Data

Saturday, November 12, 2022

1:00 PM – 3:00 PM Eastern Time

Location: Virtual Poster Hall

William Tillett, MD, PhD

Royal National Hospital for rheumatic diseases

Bath, United Kingdom

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

William Tillett1, Alexander Egeberg2, Enikö Sonkoly3, Patricia Gorecki4, Anna Tjärnlund5, Jozefien Buyze6, Sven Wegner7 and Dennis McGonagle8, 1Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases, Bath, United Kingdom, 2Department of Dermatology, Bispebjerg Hospital, Copenhagen, Denmark, 3Dermatology and Venereology Division, Karolinska Institutet; Center for Molecular Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, 4Janssen-Cilag Ltd, High Wycombe, United Kingdom, 5Janssen-Cilag AB, Solna, Sweden, 6Janssen Pharmaceutica NV, Beerse, Belgium, 7Janssen-Cilag GmbH, Neuss, Germany, 8Leeds Institute of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Medicine, University of Leeds; National Institute for Health Research, Leeds Biomedical Research Centre, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds, United Kingdom

Background/Purpose: Nail psoriasis can be difficult to treat, affects ~50% of patients with psoriasis and can involve the nail matrix (pitting, leukonychia) and/or nail bed (onycholysis, splinter haemorrhages). Evidence suggests nail psoriasis may be associated with risk of developing psoriatic arthritis, in particular distal interphalangeal joint erosion.1–3 Data to Week (Wk) 24 from VOYAGE 1 and 2, two Phase 3 clinical trials, indicate that the anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody guselkumab (GUS) is more effective than placebo and as effective as adalimumab in treating nail psoriasis.4 Furthermore, GUS is also associated with maintained Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) following treatment withdrawal in VOYAGE 2; however, nail response is not as well understood in this context.5

This VOYAGE 2 post hoc analysis evaluated nail response and its association with skin response and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in two groups, one experiencing GUS withdrawal and the other receiving continuous GUS.

Methods: Patients had moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and nail psoriasis, were initially randomised to GUS, and achieved PASI 90 at Wk 28. Patients were then re-randomised to placebo (GUS withdrawal) or GUS every 8 wks (GUS continuation). Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI; grading the most affected nail), fingernail Physician's Global Assessment (f-PGA), PASI and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) are reported as observed at Wk 0, 16, 24 and 48.

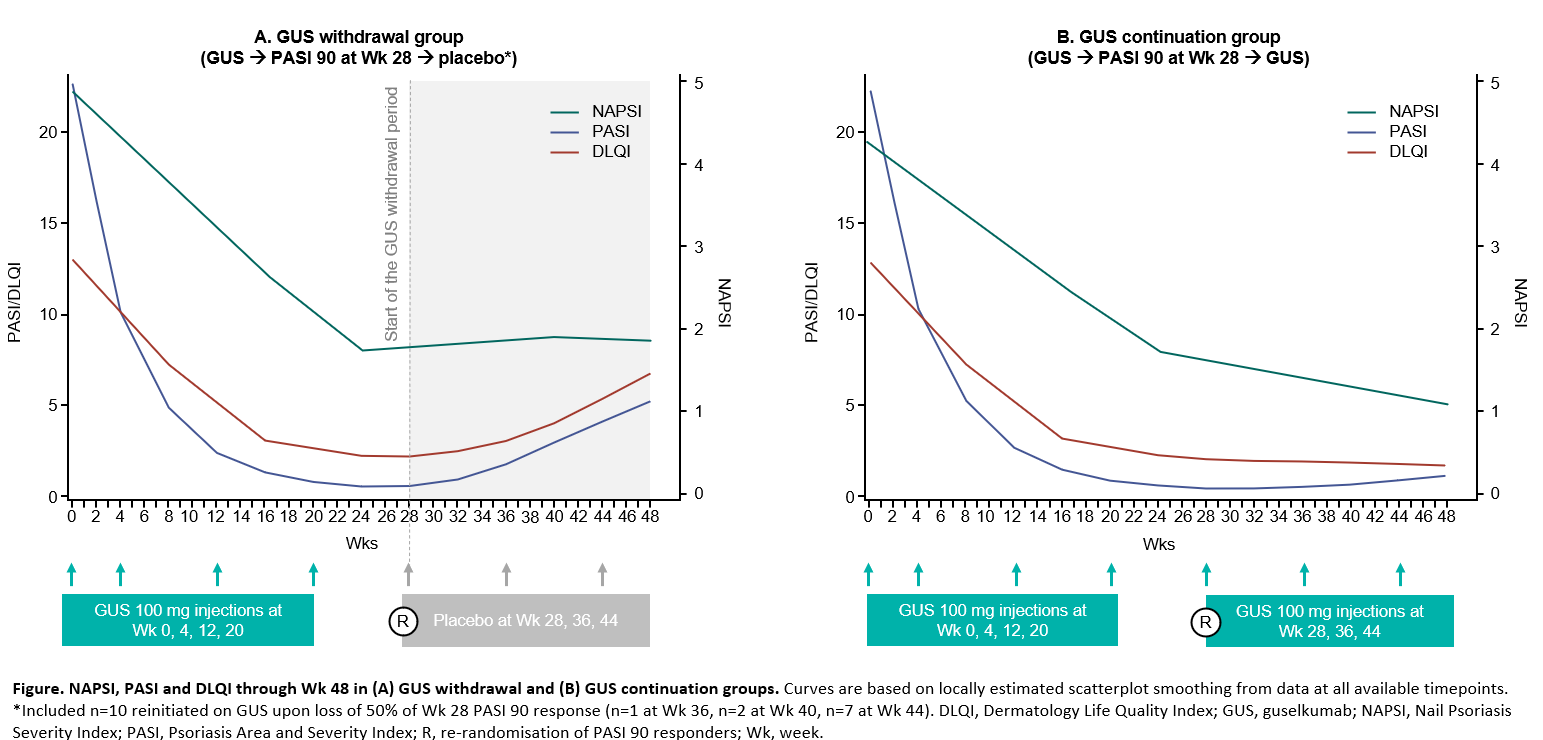

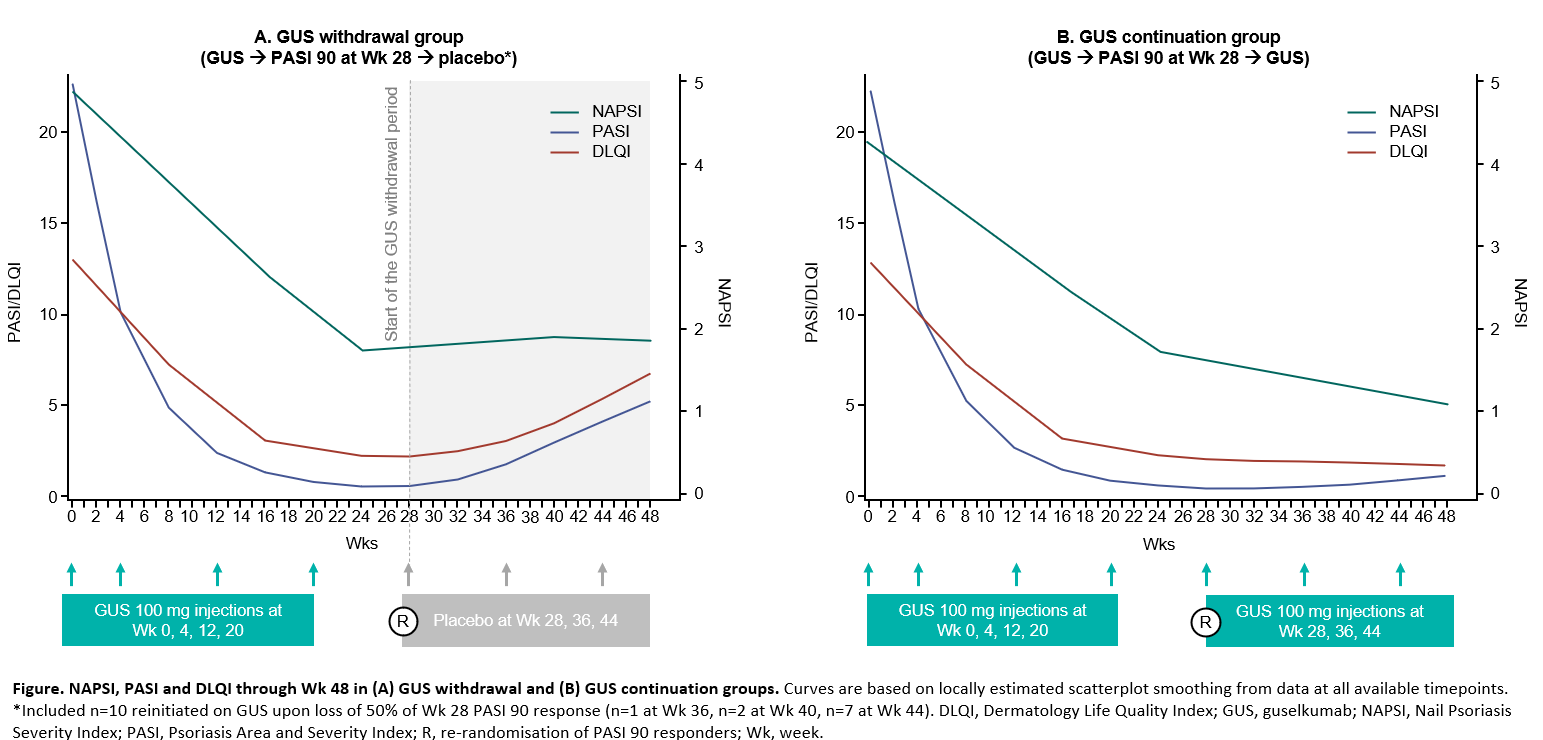

Results: Among 209 patients, NAPSI, f‑PGA, PASI and DLQI showed similar trends in both groups until Wk 24. All endpoints improved from baseline; and at Wk 24, patients in the GUS withdrawal and GUS continuation groups achieved a mean NAPSI of 1.7 and 1.8 (nail matrix 1.0 and 1.0; nail bed 0.7 and 0.8); f-PGA 0.9 and 0.9; PASI 0.6 and 0.6; and DLQI 2.2 and 2.3, respectively (Table). Nail changes continued to follow skin trends through Wk 48 (Figure); with GUS withdrawal, worsening of PASI and DLQI was proportionally greater than that of NAPSI and f-PGA; with GUS continuation, PASI and DLQI remained fairly stable, and NAPSI and f-PGA continued to improve. Nails were numerically slower to respond to GUS initiation and withdrawal than skin, with a more pronounced delay for nail matrix vs nail bed. In patients who sustained a PASI 90 response at Wk 48, despite GUS withdrawal, a high level of nail response was also maintained.

Conclusion: GUS treatment through Wk 48 improved nail psoriasis, skin psoriasis and PROs. When GUS was withdrawn, loss of response was slower in nails vs skin. These findings support that nail outcomes follow skin outcome trends with GUS treatment and that nail outcomes should contribute to evaluation of treatment efficacy and disease progression.2,3,6

References 1. Robert B. Dermatology 2010; 221 Suppl 1: 1–5; 2. Antony A et al. J Rheumatol 2019; 46: 1097–102. 3. Wilson F et al. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61: 233–39; 4. Foley P et al. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154: 676–83; 5. Conrad C et al. AAD 2021. P26573. 6. Conrad C et al. Dermatol Ther 2022; 12: 233–41.

.jpg) Data are mean (standard deviation). *n=10 reinitiated GUS upon loss of 50% of Wk 28 PASI 90

Data are mean (standard deviation). *n=10 reinitiated GUS upon loss of 50% of Wk 28 PASI 90

(n=1 at Wk 36, n=2 at Wk 40, n=7 at Wk 44); †n=107; R, re-randomisation of PASI 90 responders.

Figure. NAPSI, PASI and DLQI through Wk 48 in (A) GUS withdrawal and (B) GUS continuation groups. Curves are based on locally estimated scatterplot smoothing from data at all available time points. *Included n=10 reinitiated on GUS upon loss of 50% of Wk 28 PASI 90 response (n=1 at Wk 36, n=2 at Wk 40, n=7 at Wk 44). DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; GUS, guselkumab; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; R, re-randomisation of PASI 90 responders; Wk, week.

Figure. NAPSI, PASI and DLQI through Wk 48 in (A) GUS withdrawal and (B) GUS continuation groups. Curves are based on locally estimated scatterplot smoothing from data at all available time points. *Included n=10 reinitiated on GUS upon loss of 50% of Wk 28 PASI 90 response (n=1 at Wk 36, n=2 at Wk 40, n=7 at Wk 44). DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; GUS, guselkumab; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; R, re-randomisation of PASI 90 responders; Wk, week.

Disclosures: W. Tillett, AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB; A. Egeberg, AbbVie/Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), the Danish National Psoriasis Foundation, Eli Lilly, Janssen, the Kongelig Hofbuntmager Aage Bang Foundation, Novartis, Pfizer, the Simon Spies Foundation, Almirall, Dermavant, Galapagos NV, Galderma, LEO Pharma, Mylan, Samsung Bioepis, Sun Pharmaceuticals, UCB, UNION Therapeutics, Zuellig Pharma; E. Sonkoly, AbbVie/Abbott, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi, UCB, Pfizer; P. Gorecki, Janssen; A. Tjärnlund, Janssen; J. Buyze, Janssen; S. Wegner, Janssen; D. McGonagle, AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, UCB, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Amgen, Gilead, Pfizer.

Background/Purpose: Nail psoriasis can be difficult to treat, affects ~50% of patients with psoriasis and can involve the nail matrix (pitting, leukonychia) and/or nail bed (onycholysis, splinter haemorrhages). Evidence suggests nail psoriasis may be associated with risk of developing psoriatic arthritis, in particular distal interphalangeal joint erosion.1–3 Data to Week (Wk) 24 from VOYAGE 1 and 2, two Phase 3 clinical trials, indicate that the anti-interleukin-23 monoclonal antibody guselkumab (GUS) is more effective than placebo and as effective as adalimumab in treating nail psoriasis.4 Furthermore, GUS is also associated with maintained Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) following treatment withdrawal in VOYAGE 2; however, nail response is not as well understood in this context.5

This VOYAGE 2 post hoc analysis evaluated nail response and its association with skin response and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in two groups, one experiencing GUS withdrawal and the other receiving continuous GUS.

Methods: Patients had moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and nail psoriasis, were initially randomised to GUS, and achieved PASI 90 at Wk 28. Patients were then re-randomised to placebo (GUS withdrawal) or GUS every 8 wks (GUS continuation). Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI; grading the most affected nail), fingernail Physician's Global Assessment (f-PGA), PASI and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) are reported as observed at Wk 0, 16, 24 and 48.

Results: Among 209 patients, NAPSI, f‑PGA, PASI and DLQI showed similar trends in both groups until Wk 24. All endpoints improved from baseline; and at Wk 24, patients in the GUS withdrawal and GUS continuation groups achieved a mean NAPSI of 1.7 and 1.8 (nail matrix 1.0 and 1.0; nail bed 0.7 and 0.8); f-PGA 0.9 and 0.9; PASI 0.6 and 0.6; and DLQI 2.2 and 2.3, respectively (Table). Nail changes continued to follow skin trends through Wk 48 (Figure); with GUS withdrawal, worsening of PASI and DLQI was proportionally greater than that of NAPSI and f-PGA; with GUS continuation, PASI and DLQI remained fairly stable, and NAPSI and f-PGA continued to improve. Nails were numerically slower to respond to GUS initiation and withdrawal than skin, with a more pronounced delay for nail matrix vs nail bed. In patients who sustained a PASI 90 response at Wk 48, despite GUS withdrawal, a high level of nail response was also maintained.

Conclusion: GUS treatment through Wk 48 improved nail psoriasis, skin psoriasis and PROs. When GUS was withdrawn, loss of response was slower in nails vs skin. These findings support that nail outcomes follow skin outcome trends with GUS treatment and that nail outcomes should contribute to evaluation of treatment efficacy and disease progression.2,3,6

References 1. Robert B. Dermatology 2010; 221 Suppl 1: 1–5; 2. Antony A et al. J Rheumatol 2019; 46: 1097–102. 3. Wilson F et al. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61: 233–39; 4. Foley P et al. JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154: 676–83; 5. Conrad C et al. AAD 2021. P26573. 6. Conrad C et al. Dermatol Ther 2022; 12: 233–41.

.jpg) Data are mean (standard deviation). *n=10 reinitiated GUS upon loss of 50% of Wk 28 PASI 90

Data are mean (standard deviation). *n=10 reinitiated GUS upon loss of 50% of Wk 28 PASI 90 (n=1 at Wk 36, n=2 at Wk 40, n=7 at Wk 44); †n=107; R, re-randomisation of PASI 90 responders.

Figure. NAPSI, PASI and DLQI through Wk 48 in (A) GUS withdrawal and (B) GUS continuation groups. Curves are based on locally estimated scatterplot smoothing from data at all available time points. *Included n=10 reinitiated on GUS upon loss of 50% of Wk 28 PASI 90 response (n=1 at Wk 36, n=2 at Wk 40, n=7 at Wk 44). DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; GUS, guselkumab; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; R, re-randomisation of PASI 90 responders; Wk, week.

Figure. NAPSI, PASI and DLQI through Wk 48 in (A) GUS withdrawal and (B) GUS continuation groups. Curves are based on locally estimated scatterplot smoothing from data at all available time points. *Included n=10 reinitiated on GUS upon loss of 50% of Wk 28 PASI 90 response (n=1 at Wk 36, n=2 at Wk 40, n=7 at Wk 44). DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; GUS, guselkumab; NAPSI, Nail Psoriasis Severity Index; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; R, re-randomisation of PASI 90 responders; Wk, week.Disclosures: W. Tillett, AbbVie, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB; A. Egeberg, AbbVie/Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), the Danish National Psoriasis Foundation, Eli Lilly, Janssen, the Kongelig Hofbuntmager Aage Bang Foundation, Novartis, Pfizer, the Simon Spies Foundation, Almirall, Dermavant, Galapagos NV, Galderma, LEO Pharma, Mylan, Samsung Bioepis, Sun Pharmaceuticals, UCB, UNION Therapeutics, Zuellig Pharma; E. Sonkoly, AbbVie/Abbott, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi, UCB, Pfizer; P. Gorecki, Janssen; A. Tjärnlund, Janssen; J. Buyze, Janssen; S. Wegner, Janssen; D. McGonagle, AbbVie, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, UCB, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Amgen, Gilead, Pfizer.