Back

Abstract Session

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) including psoriatic arthritis (PsA)

Session: Abstracts: Spondyloarthritis Including PsA – Treatment I: Axial Spondyloarthritis (0542–0547)

0543: An Exploratory Analysis of the Potential Disconnect Between Objective Inflammatory Response and Clinical Response Following Certolizumab Pegol Treatment in Patients with Active Axial Spondyloarthritis

Saturday, November 12, 2022

4:45 PM – 4:55 PM Eastern Time

Location: Room 204

- MR

Martin Rudwaleit, MD

University of Bielefeld

Bielefeld, Germany

Presenting Author(s)

Martin Rudwaleit1, Filip Van den bosch2, Helena Marzo-Ortega3, Victoria Navarro-Compán4, Rachel Tham5, Thomas Kumke6, Lars Bauer6, Mindy Kim7 and Lianne Gensler8, 1University of Bielefeld, Klinikum Bielefeld, Bielefeld; Germany Klinikum Bielefeld and Charité Berlin, Germany, and Gent University, Gent, Belgium, 2Department of Internal Medicine and Paediatrics, Ghent University and VIB Centre for Inflammation Research, Ghent, Belgium, 3Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust and University of Leeds, Leeds, United Kingdom, 4Department of Rheumatology, La Paz University Hospital, IdiPaz, Madrid, Spain, 5UCB Pharma, Slough, UK, Overland Park, KS, 6UCB Pharma, Monheim am Rhein, Germany, 7UCB Pharma, Smyrna, GA, 8Department of Medicine, Division of Rheumatology, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA

Background/Purpose: In clinical trials of axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), composite measures such as Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) response criteria, Assessment of Spondyloarthritis international Society (ASAS) response criteria, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) disease activity states and ASDAS response criteria are used. However, these validated measures are largely based on patient (pt)-reported symptoms, which are likely to be confounded by other factors. In pts with active axSpA, certolizumab pegol (CZP) has demonstrated sustained clinical efficacy in clinical outcomes over 204 weeks.1 However, we hypothesize that reduction of sacroiliac joint (SIJ) and spinal inflammation following treatment with CZP, as measured by MRI and CRP levels,2 may not necessarily translate into clinical response. This post hoc analysis aims to evaluate the relationship between objective signs of inflammation (OSI), as measured by MRI/CRP, and clinical outcomes following 12 weeks of CZP treatment in pts with active axSpA.

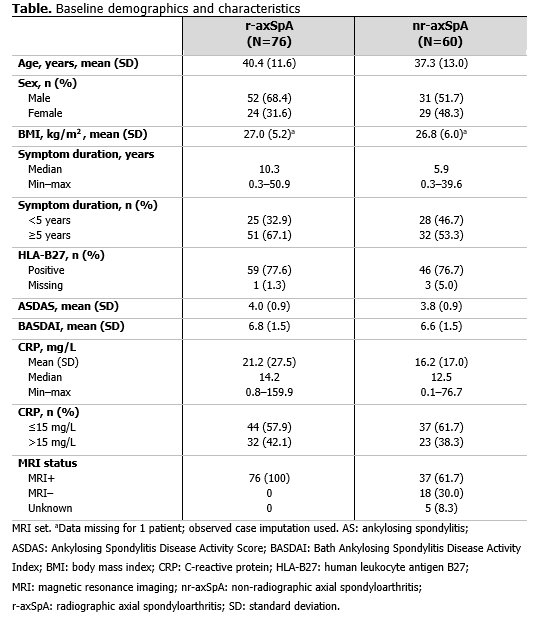

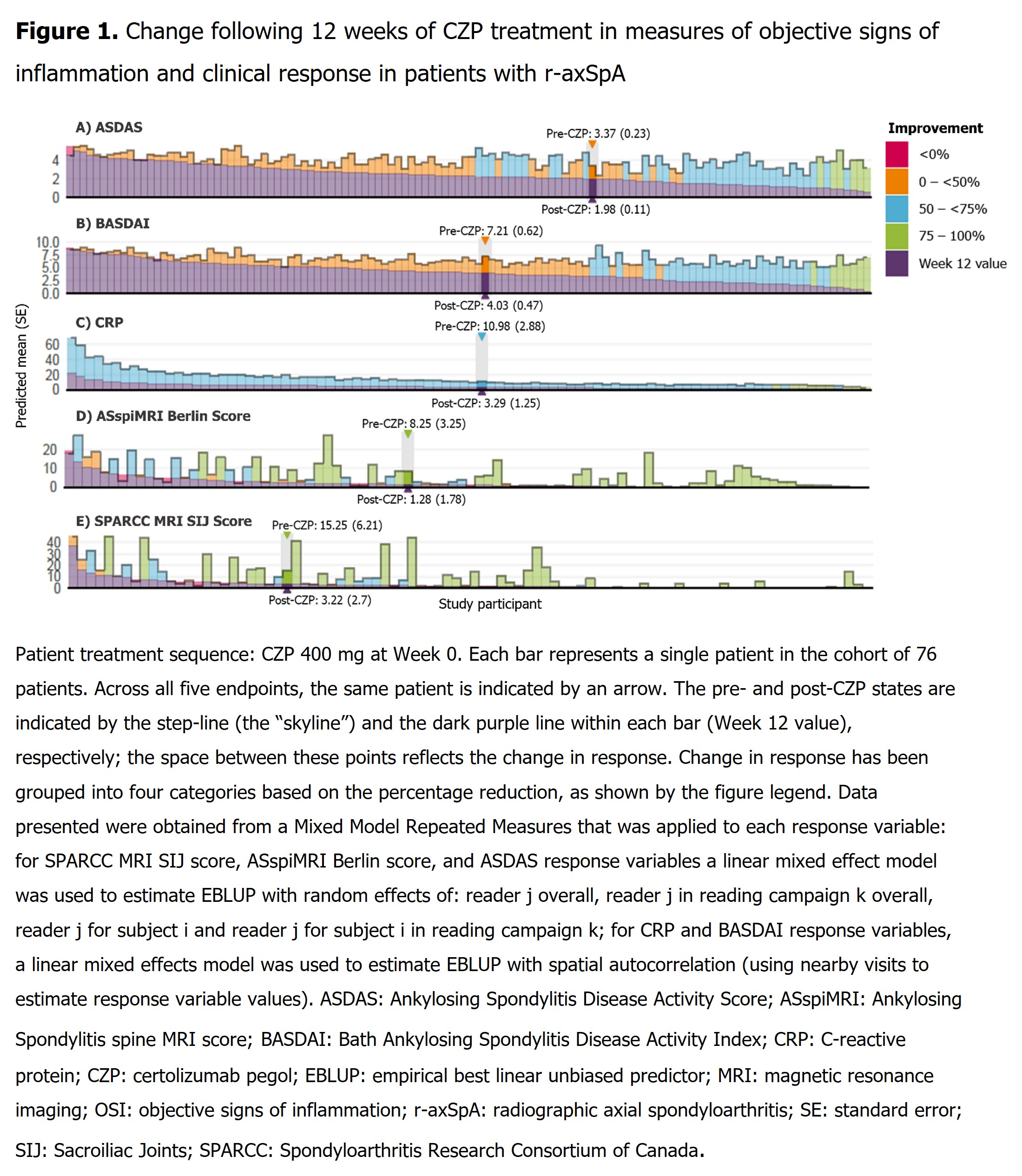

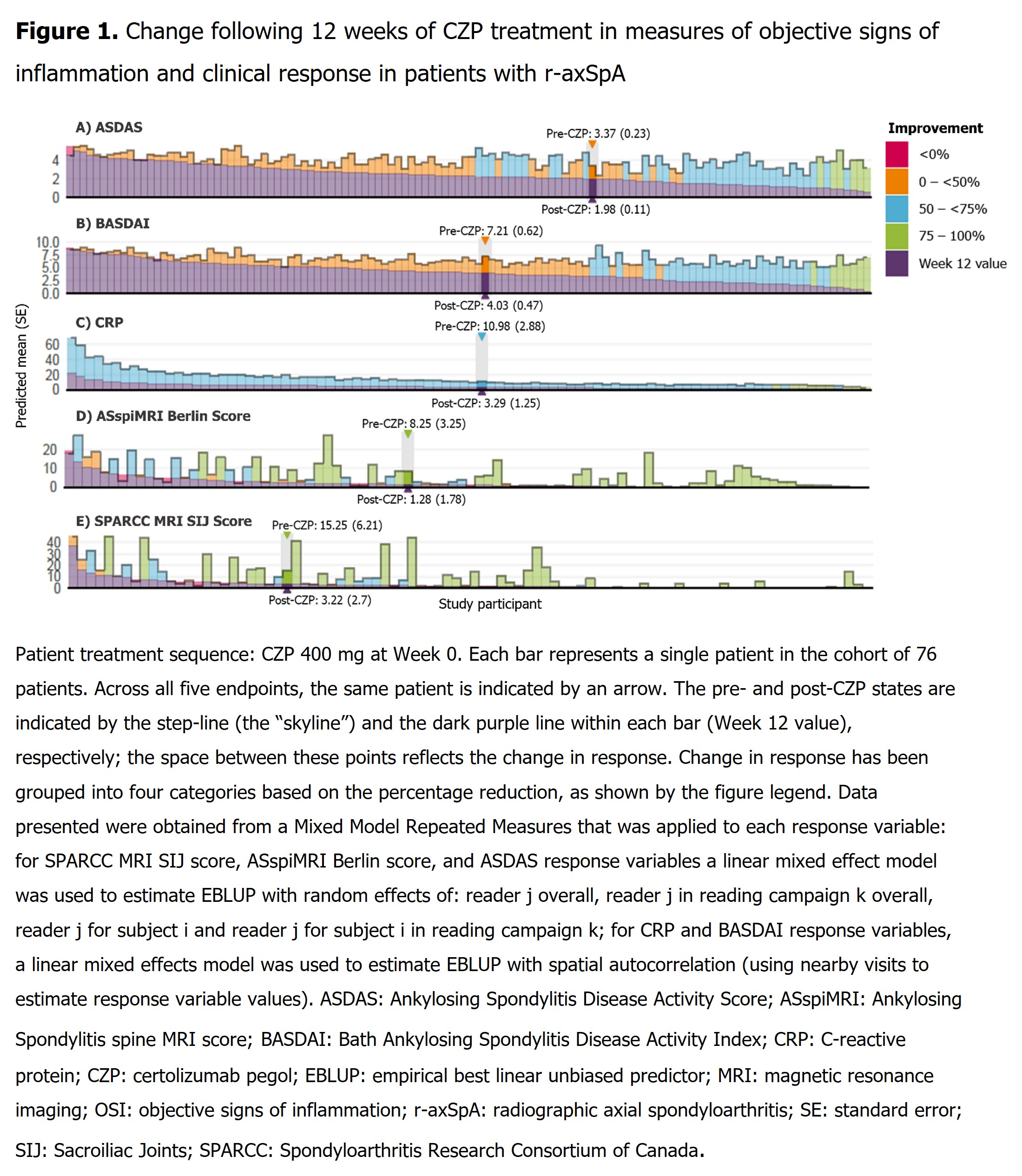

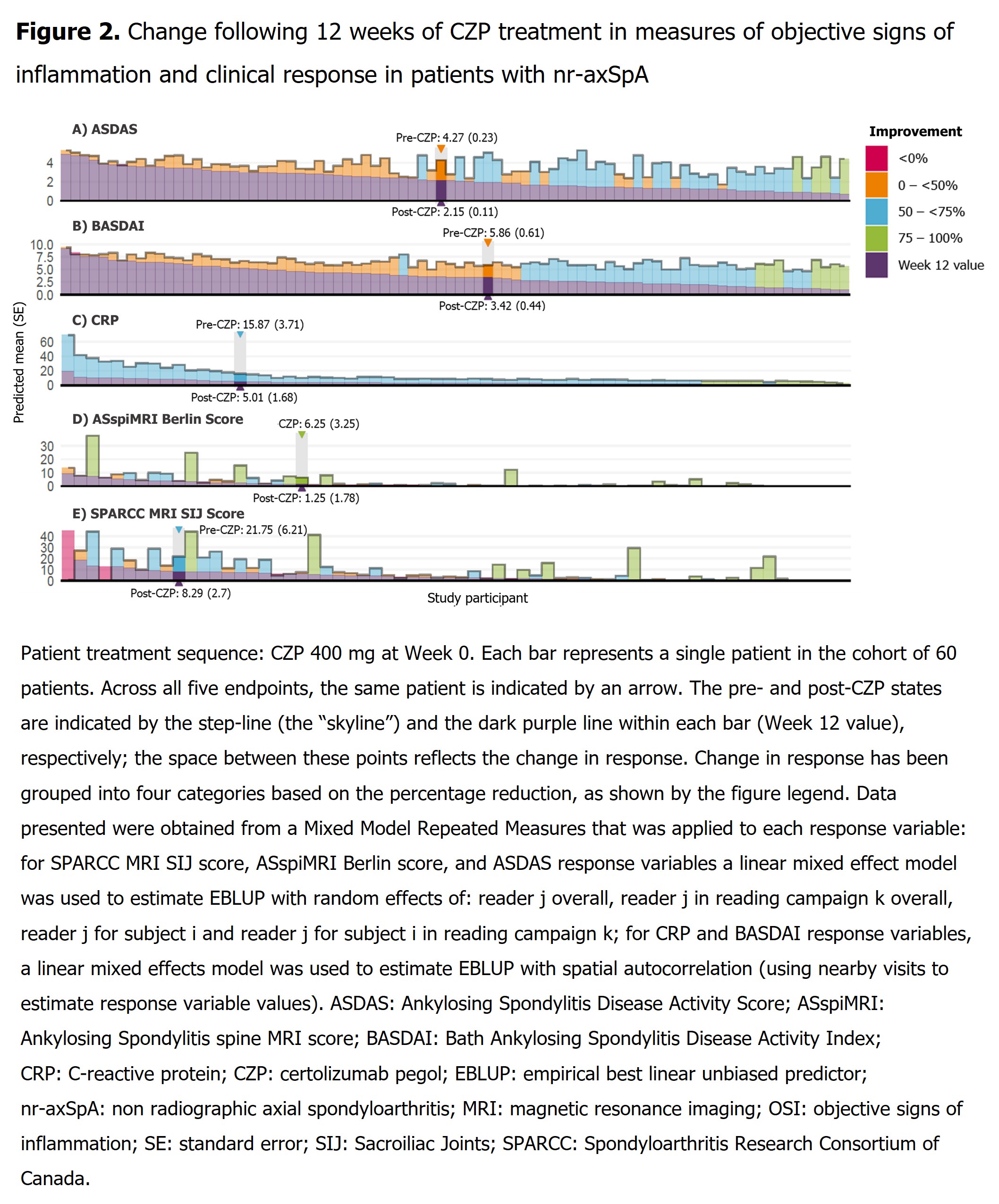

Methods: Data were analyzed from the phase 3 RAPID-axSpA study (NCT01087762).1 To improve precision of pt-level estimates, data from two independent readers were pooled in a Mixed Model for Repeated Measures for each response variable; Manhattan plots are presented for ASDAS, BASDAI, CRP, Ankylosing Spondylitis spine MRI (ASspiMRI) Berlin Score and MRI Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) SIJ score. Outcomes are reported for pts (initially randomized to either CZP, or to placebo [PBO] before switching to CZP) prior to CZP treatment (pre-CZP treatment) and following 12 weeks (wks) of treatment (post-CZP treatment).

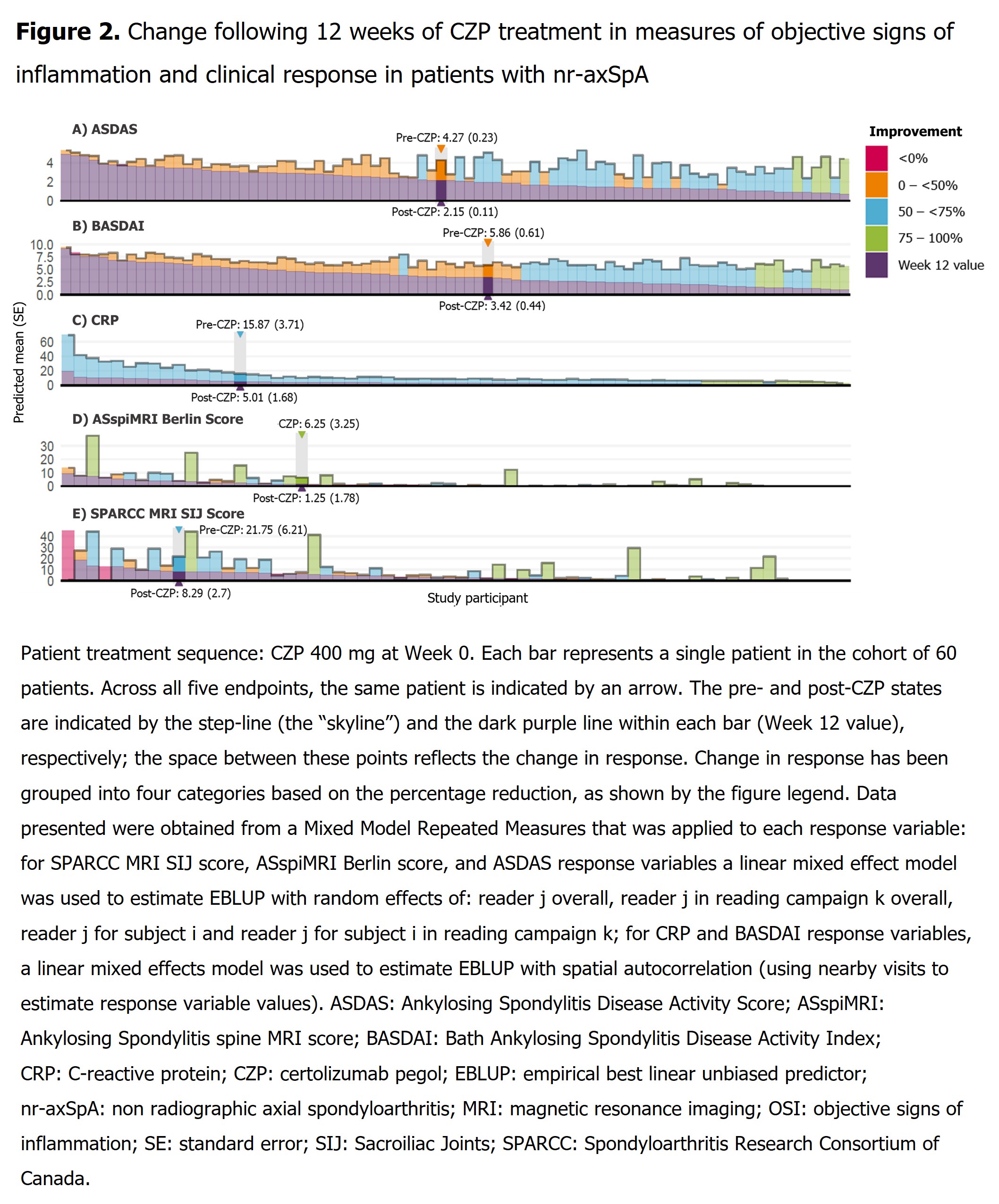

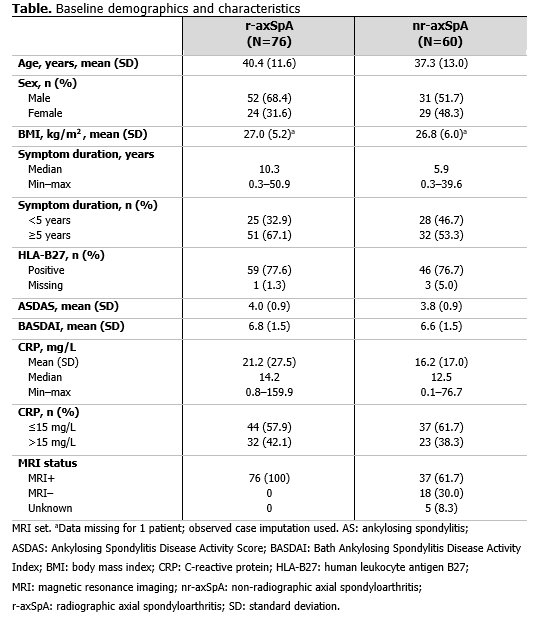

Results: 136 pts (radiographic axial spondyloarthritis [r-axSpA]: 76; non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis [nr-axSpA]: 60) had a pre-CZP and ≥1 post-CZP MRI. Pre-CZP demographics for the r-axSpA and nr-axSpA populations are presented in Table. Following CZP treatment, CRP, ASspiMRI Berlin score, and MRI SPARCC SIJ score were reduced by >50%, in the majority of pts (CRP: 136/136 [100.0%]; Berlin: 73/136 [53.7%]; SPARCC: 71/136 [52.2%]), and often by >75% (CRP: 18/136 [13.2%]; BERLIN: 53/136 [39.0%]; SPARCC: 50/136 [36.8%]) irrespective of pre-CZP value. However, only a minority of both r-axSpA (Figure 1) and nr-axSpA pts (Figure 2), showed a >50% reduction in clinical responses (BASDAI: 64/136 [47.1%]; ASDAS: 66/136 [48.5%]). These results were also observed at the individual pt level; >50% improvements in MRI/CRP inflammatory measures did not translate into similar improvements in clinical responses for the majority of pts.

Conclusion: This post hoc analysis reveals a potential disconnect between OSI, as measured by MRI and CRP, and clinical outcomes responses. In the majority of pts, CZP treatment resulted in a reduction of objective measures of inflammation, irrespective of improvements in clinical symptoms and measures of disease activity. The use of clinical response measures as clinical trial endpoints may therefore underestimate anti-inflammatory treatment effects.

References: 1. van der Heijde. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;77:699–705; 2. Braun J. RMD Open 2017;3:e000430.

Disclosures: M. Rudwaleit, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma; F. Van den bosch, AbbVie, Lilly, Galapagos, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Celgene; H. Marzo-Ortega, None; V. Navarro-Compán, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck/MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma; R. Tham, UCB Pharma, Veramed; T. Kumke, UCB Pharma; L. Bauer, UCB Pharma; M. Kim, UCB Pharma; L. Gensler, Novartis, Pfizer Inc, UCB Pharma, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Gilead, Moonlake.

Background/Purpose: In clinical trials of axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA), composite measures such as Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) response criteria, Assessment of Spondyloarthritis international Society (ASAS) response criteria, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) disease activity states and ASDAS response criteria are used. However, these validated measures are largely based on patient (pt)-reported symptoms, which are likely to be confounded by other factors. In pts with active axSpA, certolizumab pegol (CZP) has demonstrated sustained clinical efficacy in clinical outcomes over 204 weeks.1 However, we hypothesize that reduction of sacroiliac joint (SIJ) and spinal inflammation following treatment with CZP, as measured by MRI and CRP levels,2 may not necessarily translate into clinical response. This post hoc analysis aims to evaluate the relationship between objective signs of inflammation (OSI), as measured by MRI/CRP, and clinical outcomes following 12 weeks of CZP treatment in pts with active axSpA.

Methods: Data were analyzed from the phase 3 RAPID-axSpA study (NCT01087762).1 To improve precision of pt-level estimates, data from two independent readers were pooled in a Mixed Model for Repeated Measures for each response variable; Manhattan plots are presented for ASDAS, BASDAI, CRP, Ankylosing Spondylitis spine MRI (ASspiMRI) Berlin Score and MRI Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium of Canada (SPARCC) SIJ score. Outcomes are reported for pts (initially randomized to either CZP, or to placebo [PBO] before switching to CZP) prior to CZP treatment (pre-CZP treatment) and following 12 weeks (wks) of treatment (post-CZP treatment).

Results: 136 pts (radiographic axial spondyloarthritis [r-axSpA]: 76; non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis [nr-axSpA]: 60) had a pre-CZP and ≥1 post-CZP MRI. Pre-CZP demographics for the r-axSpA and nr-axSpA populations are presented in Table. Following CZP treatment, CRP, ASspiMRI Berlin score, and MRI SPARCC SIJ score were reduced by >50%, in the majority of pts (CRP: 136/136 [100.0%]; Berlin: 73/136 [53.7%]; SPARCC: 71/136 [52.2%]), and often by >75% (CRP: 18/136 [13.2%]; BERLIN: 53/136 [39.0%]; SPARCC: 50/136 [36.8%]) irrespective of pre-CZP value. However, only a minority of both r-axSpA (Figure 1) and nr-axSpA pts (Figure 2), showed a >50% reduction in clinical responses (BASDAI: 64/136 [47.1%]; ASDAS: 66/136 [48.5%]). These results were also observed at the individual pt level; >50% improvements in MRI/CRP inflammatory measures did not translate into similar improvements in clinical responses for the majority of pts.

Conclusion: This post hoc analysis reveals a potential disconnect between OSI, as measured by MRI and CRP, and clinical outcomes responses. In the majority of pts, CZP treatment resulted in a reduction of objective measures of inflammation, irrespective of improvements in clinical symptoms and measures of disease activity. The use of clinical response measures as clinical trial endpoints may therefore underestimate anti-inflammatory treatment effects.

References: 1. van der Heijde. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;77:699–705; 2. Braun J. RMD Open 2017;3:e000430.

Disclosures: M. Rudwaleit, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), Boehringer-Ingelheim, Chugai, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma; F. Van den bosch, AbbVie, Lilly, Galapagos, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Celgene; H. Marzo-Ortega, None; V. Navarro-Compán, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck/MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB Pharma; R. Tham, UCB Pharma, Veramed; T. Kumke, UCB Pharma; L. Bauer, UCB Pharma; M. Kim, UCB Pharma; L. Gensler, Novartis, Pfizer Inc, UCB Pharma, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Gilead, Moonlake.