Back

Poster Session B

Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Session: (0671–0694) Antiphospholipid Syndrome Poster

0680: Association of Environmental Risk Factors with Antiphospholipid Antibodies and Thrombosis in 1199 International Patients Referred for Suspected Antiphospholipid Syndrome

Sunday, November 13, 2022

9:00 AM – 10:30 AM Eastern Time

Location: Virtual Poster Hall

Medha Barbhaiya, MD, MPH

Hospital for Special Surgery

New York, NY, United States

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Medha Barbhaiya1, Deanna Jannat-Khah, DrPH, MSPH1, Jonah Levine1, Karen Costenbader2 and Doruk Erkan1, 1Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY, 2Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA

Background/Purpose: Whether environmental risk factors induce antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) positivity and increase the risk of arterial thrombosis (AT) and venous thromboembolism (VTE) in aPL-positive patients remains to be determined. Using international data, we evaluated the association of certain environmental stimuli, including oral contraceptive (OC) use, cigarette smoking, and obesity with aPL profile, overall and stratified by thrombosis history.

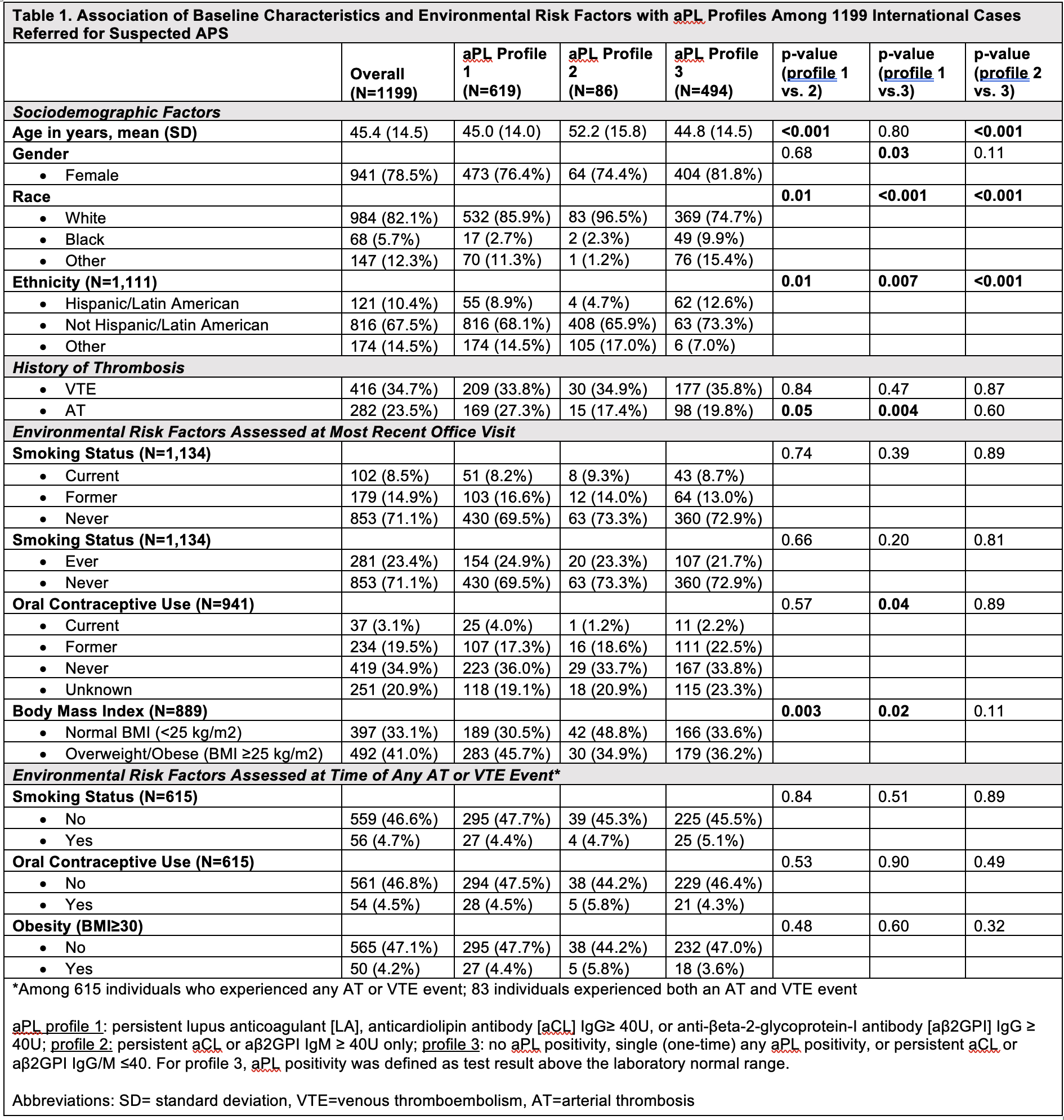

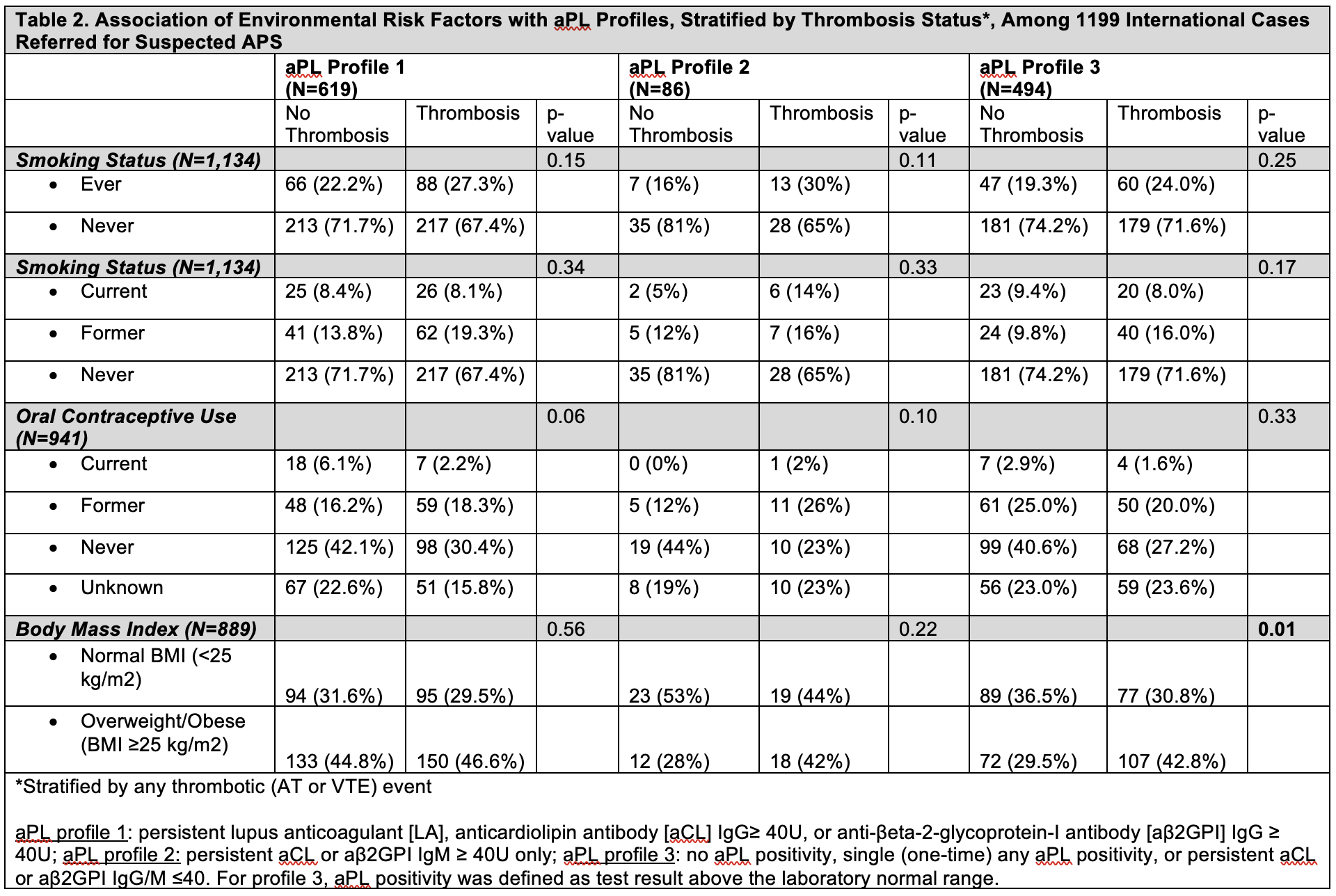

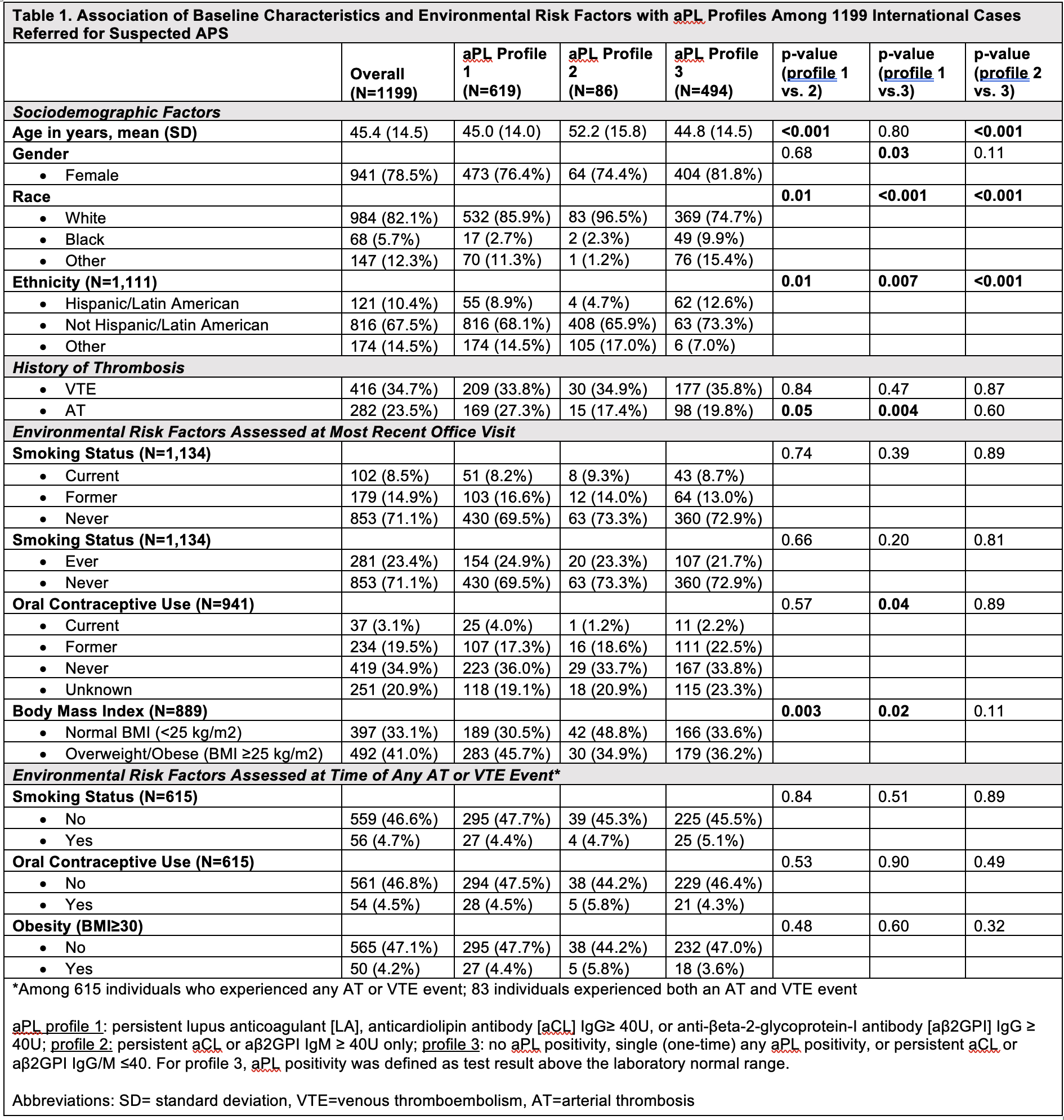

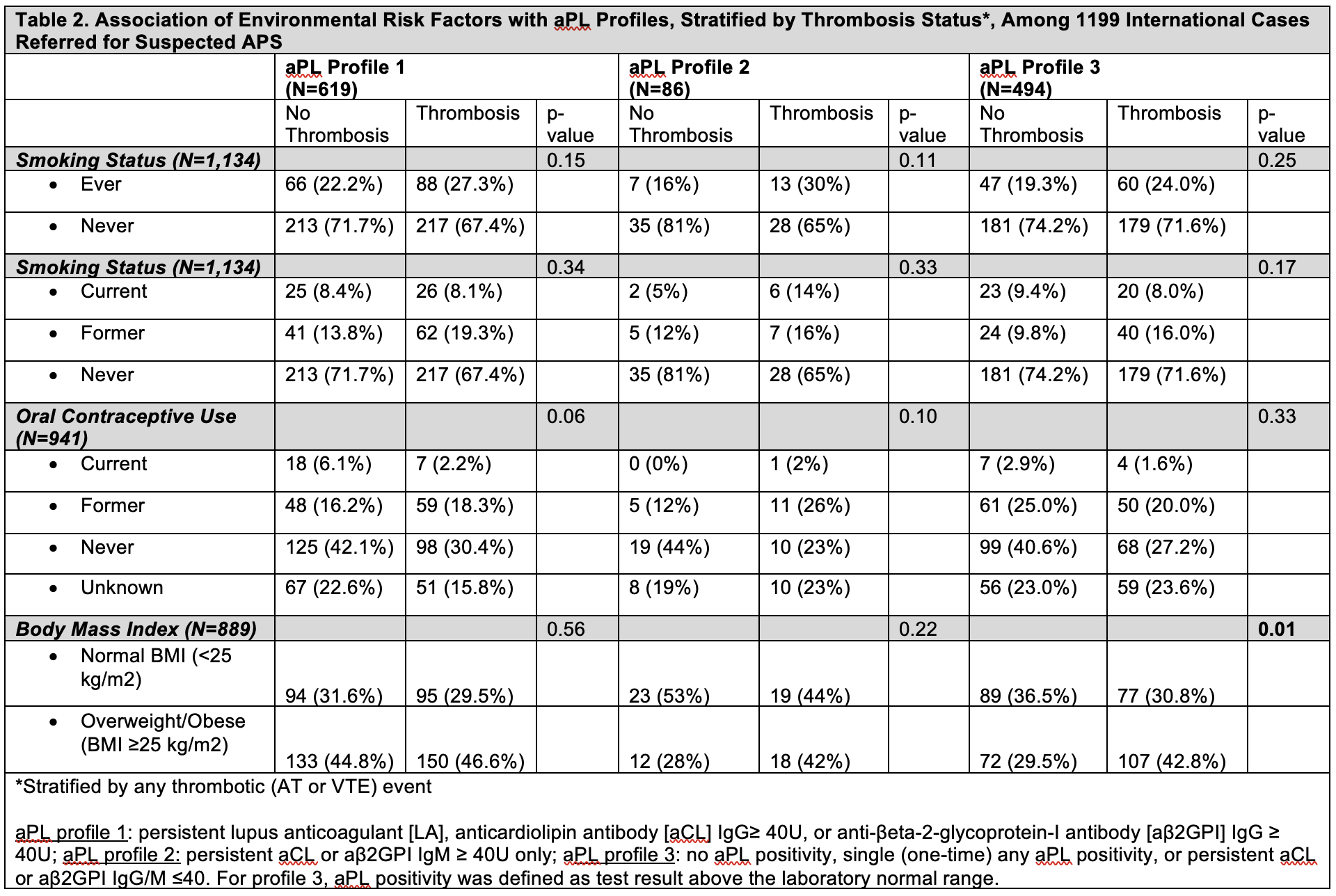

Methods: As part of the new APS classification criteria development efforts, we collected data from 1199 patients referred for “suspected APS” (aPL-positive/negative cases with/without history of thrombosis) to academic centers in North America, South America, Europe, and Asia. This included demographics, aPL profile, and medical history. Smoking history, OC use, and most recent body mass index (BMI) were collected both at the time of an AT or VTE event, and at the last office visit. We used t-tests or chi-square tests to evaluate the association of environmental factors with three mutually exclusive aPL profiles (aPL profile 1: persistent lupus anticoagulant [LA], anticardiolipin antibody [aCL] IgG≥ 40U, or anti-βeta-2-glycoprotein-I antibody [aβ2GPI] IgG ≥ 40U; profile 2: persistent aCL or aβ2GPI IgM ≥ 40U only; profile 3: no aPL positivity, single (one-time) any aPL positivity, or persistent aCL or aβ2GPI IgG/M ≤40), overall and stratified by history of thrombosis.

Results: Mean age of 1199 patients was 45.4 years (SD 14.5); 78.5% female, 82.1% White, 10.1% Hispanic/Latinx. aPL profile 1 included 619 patients (51.6%), profile 2 included 86 patients (7.2%), and profile 3 included 494 patients (41.2%). Sociodemographic factors significantly varied across all three aPL profiles; AT events were more prevalent in aPL profile 1 versus 3 (p=0.004), but VTE was not associated with aPL profile (Table 1). Among 23.4% of ‘ever’ smokers, 8.5% were current smokers. No association was demonstrated for current or ever smoking with aPL profiles. Of the 22.6% reporting ‘ever’ OC use, 3.1% were current users; OC status differed significantly in aPL profile 1 versus 3 (p=0.04), with a higher percentage of current OC users in aPL profile 1. Of the 41% in the cohort who were overweight/obese (BMI ≥25), overweight/obesity was significantly higher in aPL profile 1 versus 2 (p=0.003) and versus 3 (p=0.02). Less than 6% of patients had active smoking, OC use, and/or BMI≥25 at the time of AT/VTE event, which were not different between different aPL profiles (Table 1). When stratifying aPL profile by thrombosis history, recent overweight/obesity was significantly higher in the thrombosis (versus no thrombosis) group for aPL profile 3 (Table 2).

Conclusion: Within a cohort of international patients referred for suspected APS, OC use and recent overweight/obesity were significantly associated with a clinically significant aPL profile of persistent LAC and/or aCL/aβ2GPI IgG ≥ 40U. No association of smoking status or risk factors at the time of thrombosis were demonstrated, possibly due to low prevalence in our cohort. Multivariable analyses accounting for sociodemographics, concomitant systemic rheumatic disease, and other thrombosis risk factors will be performed to confirm these findings.

Disclosures: M. Barbhaiya, None; D. Jannat-Khah, DrPH, MSPH, Cytodyn, AstraZeneca, Walgreens; J. Levine, None; K. Costenbader, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Amgen, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, GlaxoSmithKline(GSK), Gilead, Exagen, Neutrolis, Cel-Sci, Alkermes; D. Erkan, None.

Background/Purpose: Whether environmental risk factors induce antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) positivity and increase the risk of arterial thrombosis (AT) and venous thromboembolism (VTE) in aPL-positive patients remains to be determined. Using international data, we evaluated the association of certain environmental stimuli, including oral contraceptive (OC) use, cigarette smoking, and obesity with aPL profile, overall and stratified by thrombosis history.

Methods: As part of the new APS classification criteria development efforts, we collected data from 1199 patients referred for “suspected APS” (aPL-positive/negative cases with/without history of thrombosis) to academic centers in North America, South America, Europe, and Asia. This included demographics, aPL profile, and medical history. Smoking history, OC use, and most recent body mass index (BMI) were collected both at the time of an AT or VTE event, and at the last office visit. We used t-tests or chi-square tests to evaluate the association of environmental factors with three mutually exclusive aPL profiles (aPL profile 1: persistent lupus anticoagulant [LA], anticardiolipin antibody [aCL] IgG≥ 40U, or anti-βeta-2-glycoprotein-I antibody [aβ2GPI] IgG ≥ 40U; profile 2: persistent aCL or aβ2GPI IgM ≥ 40U only; profile 3: no aPL positivity, single (one-time) any aPL positivity, or persistent aCL or aβ2GPI IgG/M ≤40), overall and stratified by history of thrombosis.

Results: Mean age of 1199 patients was 45.4 years (SD 14.5); 78.5% female, 82.1% White, 10.1% Hispanic/Latinx. aPL profile 1 included 619 patients (51.6%), profile 2 included 86 patients (7.2%), and profile 3 included 494 patients (41.2%). Sociodemographic factors significantly varied across all three aPL profiles; AT events were more prevalent in aPL profile 1 versus 3 (p=0.004), but VTE was not associated with aPL profile (Table 1). Among 23.4% of ‘ever’ smokers, 8.5% were current smokers. No association was demonstrated for current or ever smoking with aPL profiles. Of the 22.6% reporting ‘ever’ OC use, 3.1% were current users; OC status differed significantly in aPL profile 1 versus 3 (p=0.04), with a higher percentage of current OC users in aPL profile 1. Of the 41% in the cohort who were overweight/obese (BMI ≥25), overweight/obesity was significantly higher in aPL profile 1 versus 2 (p=0.003) and versus 3 (p=0.02). Less than 6% of patients had active smoking, OC use, and/or BMI≥25 at the time of AT/VTE event, which were not different between different aPL profiles (Table 1). When stratifying aPL profile by thrombosis history, recent overweight/obesity was significantly higher in the thrombosis (versus no thrombosis) group for aPL profile 3 (Table 2).

Conclusion: Within a cohort of international patients referred for suspected APS, OC use and recent overweight/obesity were significantly associated with a clinically significant aPL profile of persistent LAC and/or aCL/aβ2GPI IgG ≥ 40U. No association of smoking status or risk factors at the time of thrombosis were demonstrated, possibly due to low prevalence in our cohort. Multivariable analyses accounting for sociodemographics, concomitant systemic rheumatic disease, and other thrombosis risk factors will be performed to confirm these findings.

Disclosures: M. Barbhaiya, None; D. Jannat-Khah, DrPH, MSPH, Cytodyn, AstraZeneca, Walgreens; J. Levine, None; K. Costenbader, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Amgen, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, GlaxoSmithKline(GSK), Gilead, Exagen, Neutrolis, Cel-Sci, Alkermes; D. Erkan, None.