Back

Poster Session D

Session: (1950–1979) RA – Diagnosis, Manifestations, and Outcomes Poster IV

1967: Sex Differences in Employment Outcomes in Patients with Recent Onset Rheumatoid Arthritis

Monday, November 14, 2022

1:00 PM – 3:00 PM Eastern Time

Location: Virtual Poster Hall

- CH

Carol Hitchon, MD, MSc

University of Manitoba

Winnipeg, MB, Canada

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Carol Hitchon1, Marie-France Valois2, orit schieir2, Louis Bessette3, Gilles Boire4, Susan Bartlett5, Glen Hazlewood6, Edward Keystone7, Janet Pope8, Carter Thorne9, Diane Tin10 and Vivian Bykerk11, 1University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2McGill University, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3Centre de l'Ostoporose et de Rhumatologie de Québec, Québec, QC, Canada, 4Universite de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, QC, Canada, 5McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 6University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 7Keystone Consulting Enterprises Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada, 8University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada, 9Southlake Regional Health Centre, Newmarket, ON, Canada, 10The Arthritis Program Research Group, Newmarket, ON, Canada, 11Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY

Background/Purpose: Early work cessation and reduced work and activity productivity are significant contributors to the personal and societal costs associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). We sought to describe sex differences in work status and work productivity over time in newly diagnosed RA patients and to identify factors associated with work cessation.

Methods: Data were from early RA patients (< 1 year of symptoms at baseline), followed by rheumatologists across Canada and treated with disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug therapies (DMARDs) according to Treat-2-Target guidelines. Between November 2011 to March 2020, 945 participants reported work status (employed or not-employed), reasons for stopping work (RA, retirement, other) and work productivity as assessed by the Work Productivity and Activity Index (WPAI) annually over the first five years of follow-up. WPAI scores for overall work productivity loss with subscores for absenteeism (time away from work) and presenteeism (reduced productivity at work) and reduced general activity are expressed as impairment percentages (%) with higher numbers indicating greater impairment and less productivity. We used GEE regression models to estimate associations of sociodemographic and disease related variables with stopping work due to RA or early retirement (defined as retiring prior to age 65, the average retirement age in Canada). The analysis was stratified by sex. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals are reported.

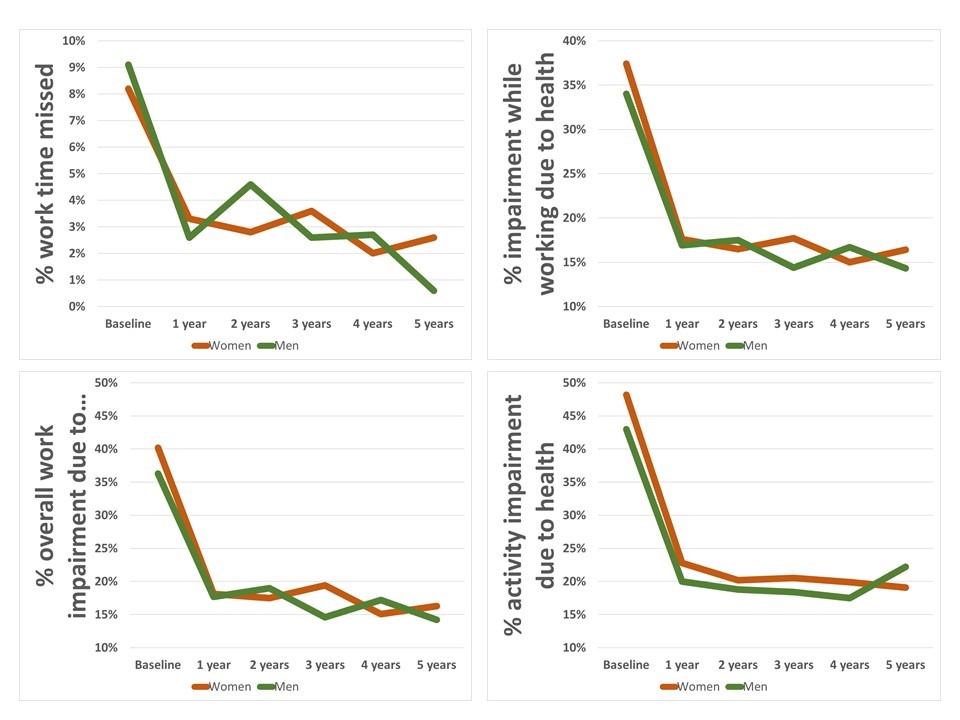

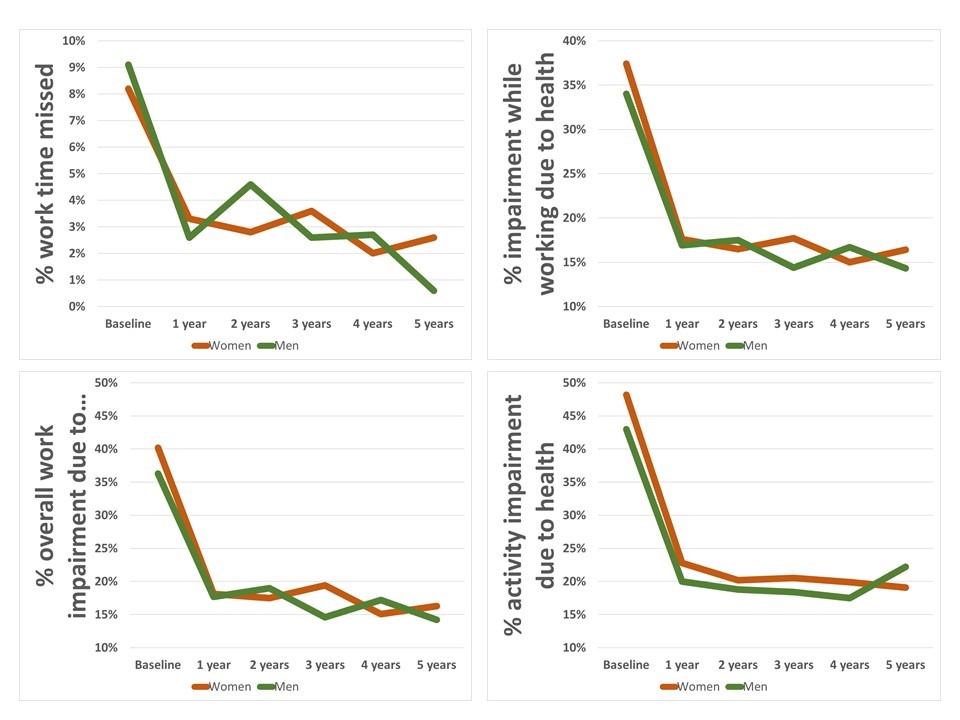

Results: At baseline 479 (51%) were employed (131/278 males; 348/667 females). Of those not working at baseline, 2% had stopped working due to RA, 62% were retired and 36% had stopped working for other reasons. At baseline, participants reported mean 39.2% (29.6) overall work impairment, mean 8.5% (19.1) absenteeism, and mean 36.5% (27.9) presenteeism. WPAI scores improved during followup and were similar for males and females (Figure). Of those employed at baseline, 14% (47 women, 20 men) stopped working due to RA or retired early during the first 5 years of follow-up. Only 12 (29%) of those who stopped working due to RA returned to work (8/17 males 47%; 4/24 females 17%). Factors associated with stopping work due to RA or retiring early were for females age (OR 1.31; 1.16, 1.45), whereas previous visit pain (OR 0.9; 0.82, 0.99), oral steroid use (OR 0.38; 0.15, 0.92) and worse mental health RAND-12 mental health t-score increase of 5 (OR 0.87; 0.77, 0.97) reduced work stoppage. For males, stopping work was associated with previous visit pain (OR 1.31; 1.01,1.70) whereas increased household size of one other (OR 0.22; 0.05, 0.95), and mental health (OR 0.79; 0.63,0.99) reduced work loss.

Conclusion: Both men and women report impairments with work and leisure activities that improve over time but plateau. A small proportion of ERA patients stop work due to RA or report retiring early with sex differences between those that stop vs continue driven mostly by age, number of people living in the household, pain and mental health. Women that stop working due to RA are less likely than men to report returning to work. Interventions to optimize continued engagement in work may improve productivity outcomes for RA patients and their employers.

WPAI scores over the first five years of follow-up stratified by sex

WPAI scores over the first five years of follow-up stratified by sex

Disclosures: C. Hitchon, Pfizer Canada, Astra-Zeneca Canada, Pfizer; M. Valois, None; o. schieir, None; L. Bessette, AbbVie/Abbott, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Genzyme, UCB, Gilead, Merck/MSD, Organon, Roche; G. Boire, AbbVie/Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Janssen, Eli Lilly, Merck/MSD, Novartis, Orimed Pharma, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Teva, Viatris, Amgen, Celgene; S. Bartlett, Pfizer, Novartis, Merck/MSD, Janssen, AbbVie/Abbott, Organon; G. Hazlewood, None; E. Keystone, AbbVie/Abbott, Amgen, Gilead, Eli Lilly, Merck/MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Celltrion, Myriad Autoimmune, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Inc, Genentech, Janssen, Sandoz, Samsung Bioepsis, AstraZeneca, Samsung Bioepsis; J. Pope, AbbVie/Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Eli Lilly, merk, Roche, Seattle Genetics, UCB, Actelion, Amgen, Bayer, Eicos Sciences, Emerald, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim; C. Thorne, AbbVie/Abbott, Amgen, Celgene, CaREBiodam, Centocor, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Medexus/Medac, Merck; D. Tin, None; V. Bykerk, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Genzyme, Brainstorm, Gilead, Regeneron, UCB, Pfizer, Sanofi, Aventis.

Background/Purpose: Early work cessation and reduced work and activity productivity are significant contributors to the personal and societal costs associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). We sought to describe sex differences in work status and work productivity over time in newly diagnosed RA patients and to identify factors associated with work cessation.

Methods: Data were from early RA patients (< 1 year of symptoms at baseline), followed by rheumatologists across Canada and treated with disease modifying anti-rheumatic drug therapies (DMARDs) according to Treat-2-Target guidelines. Between November 2011 to March 2020, 945 participants reported work status (employed or not-employed), reasons for stopping work (RA, retirement, other) and work productivity as assessed by the Work Productivity and Activity Index (WPAI) annually over the first five years of follow-up. WPAI scores for overall work productivity loss with subscores for absenteeism (time away from work) and presenteeism (reduced productivity at work) and reduced general activity are expressed as impairment percentages (%) with higher numbers indicating greater impairment and less productivity. We used GEE regression models to estimate associations of sociodemographic and disease related variables with stopping work due to RA or early retirement (defined as retiring prior to age 65, the average retirement age in Canada). The analysis was stratified by sex. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals are reported.

Results: At baseline 479 (51%) were employed (131/278 males; 348/667 females). Of those not working at baseline, 2% had stopped working due to RA, 62% were retired and 36% had stopped working for other reasons. At baseline, participants reported mean 39.2% (29.6) overall work impairment, mean 8.5% (19.1) absenteeism, and mean 36.5% (27.9) presenteeism. WPAI scores improved during followup and were similar for males and females (Figure). Of those employed at baseline, 14% (47 women, 20 men) stopped working due to RA or retired early during the first 5 years of follow-up. Only 12 (29%) of those who stopped working due to RA returned to work (8/17 males 47%; 4/24 females 17%). Factors associated with stopping work due to RA or retiring early were for females age (OR 1.31; 1.16, 1.45), whereas previous visit pain (OR 0.9; 0.82, 0.99), oral steroid use (OR 0.38; 0.15, 0.92) and worse mental health RAND-12 mental health t-score increase of 5 (OR 0.87; 0.77, 0.97) reduced work stoppage. For males, stopping work was associated with previous visit pain (OR 1.31; 1.01,1.70) whereas increased household size of one other (OR 0.22; 0.05, 0.95), and mental health (OR 0.79; 0.63,0.99) reduced work loss.

Conclusion: Both men and women report impairments with work and leisure activities that improve over time but plateau. A small proportion of ERA patients stop work due to RA or report retiring early with sex differences between those that stop vs continue driven mostly by age, number of people living in the household, pain and mental health. Women that stop working due to RA are less likely than men to report returning to work. Interventions to optimize continued engagement in work may improve productivity outcomes for RA patients and their employers.

WPAI scores over the first five years of follow-up stratified by sex

WPAI scores over the first five years of follow-up stratified by sexDisclosures: C. Hitchon, Pfizer Canada, Astra-Zeneca Canada, Pfizer; M. Valois, None; o. schieir, None; L. Bessette, AbbVie/Abbott, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi-Genzyme, UCB, Gilead, Merck/MSD, Organon, Roche; G. Boire, AbbVie/Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Janssen, Eli Lilly, Merck/MSD, Novartis, Orimed Pharma, Pfizer, Samsung Bioepis, Teva, Viatris, Amgen, Celgene; S. Bartlett, Pfizer, Novartis, Merck/MSD, Janssen, AbbVie/Abbott, Organon; G. Hazlewood, None; E. Keystone, AbbVie/Abbott, Amgen, Gilead, Eli Lilly, Merck/MSD, Pfizer, Sanofi, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Celltrion, Myriad Autoimmune, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Inc, Genentech, Janssen, Sandoz, Samsung Bioepsis, AstraZeneca, Samsung Bioepsis; J. Pope, AbbVie/Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Eli Lilly, merk, Roche, Seattle Genetics, UCB, Actelion, Amgen, Bayer, Eicos Sciences, Emerald, Gilead, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, Sandoz, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim; C. Thorne, AbbVie/Abbott, Amgen, Celgene, CaREBiodam, Centocor, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Medexus/Medac, Merck; D. Tin, None; V. Bykerk, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb(BMS), Genzyme, Brainstorm, Gilead, Regeneron, UCB, Pfizer, Sanofi, Aventis.