Back

Poster Session B

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

Session: (0629–0670) SLE – Etiology and Pathogenesis Poster

0631: Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Community Vulnerability: Associations with Lupus-Related Autoantibodies and Disease

Sunday, November 13, 2022

9:00 AM – 10:30 AM Eastern Time

Location: Virtual Poster Hall

- EV

Emily Vara, DO

Medical University of South Carolina

Charleston, SC, United States

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Emily Vara, Dulaney Wilson, John Pearce, Jim Oates and Diane Kamen, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC

Background/Purpose: Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a class of persistent organic pollutants found in nonstick products, water repellant fabrics, fire-retardant foams, and food packaging. Highly stable, the compounds persist in soil and water, bioaccumulate, and are found in the blood and tissues of animals and humans. Several PFAS, including perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), have been associated with negative health effects through hormone disruption and immunologic dysfunction.

This ongoing study explores the associations between PFAS biomarkers, autoimmunity, and neighborhood-level social determinants of health among African Americans participating in a population-based cohort study.

Methods: Data was utilized from a longitudinal study of Gullah African American patients with SLE and non-SLE controls. Demographics, medical history, Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) (incorporating socioeconomic status, household composition, race/ethnicity/language, and housing/transportation), antinuclear antibody (ANA) status and titer, serum PFOA concentration (ng/mL), and serum PFOS concentration (ng/ml) from in-person visits from 2003-2019 were included. Spatial overlays were applied to assign census tract identifiers and obtain SVI data for the participants. Statistical analysis using univariate and multivariate linear regression was performed.

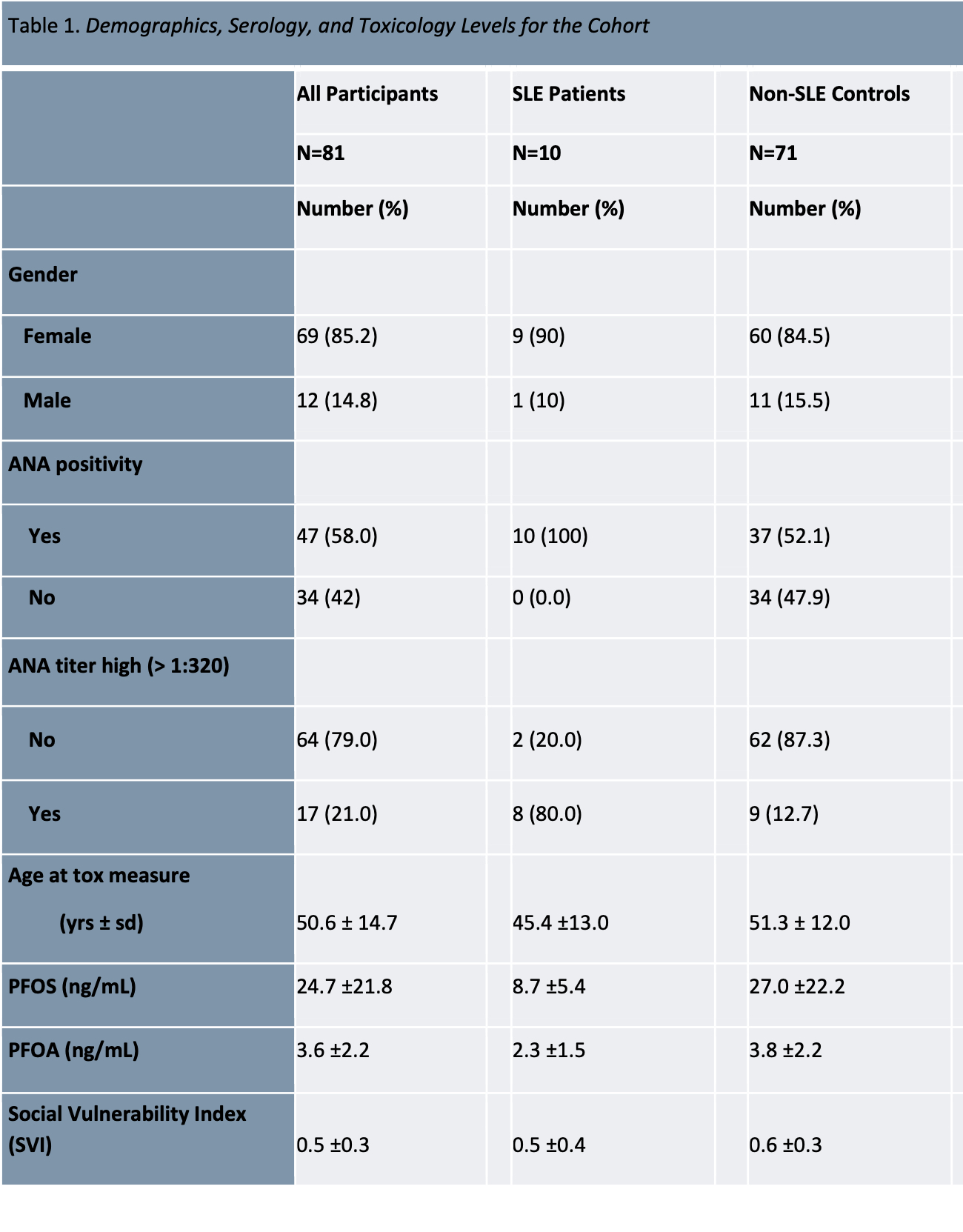

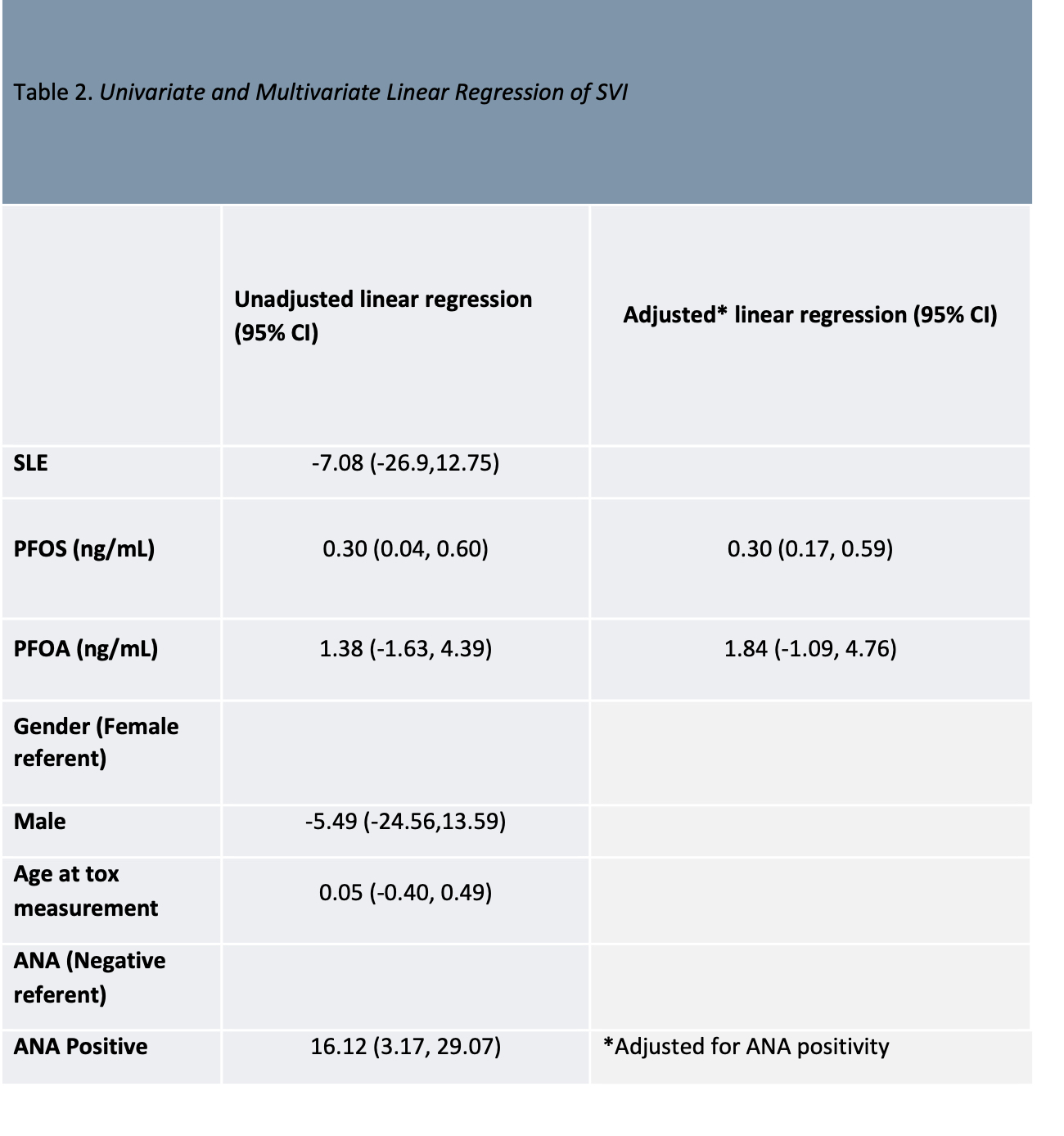

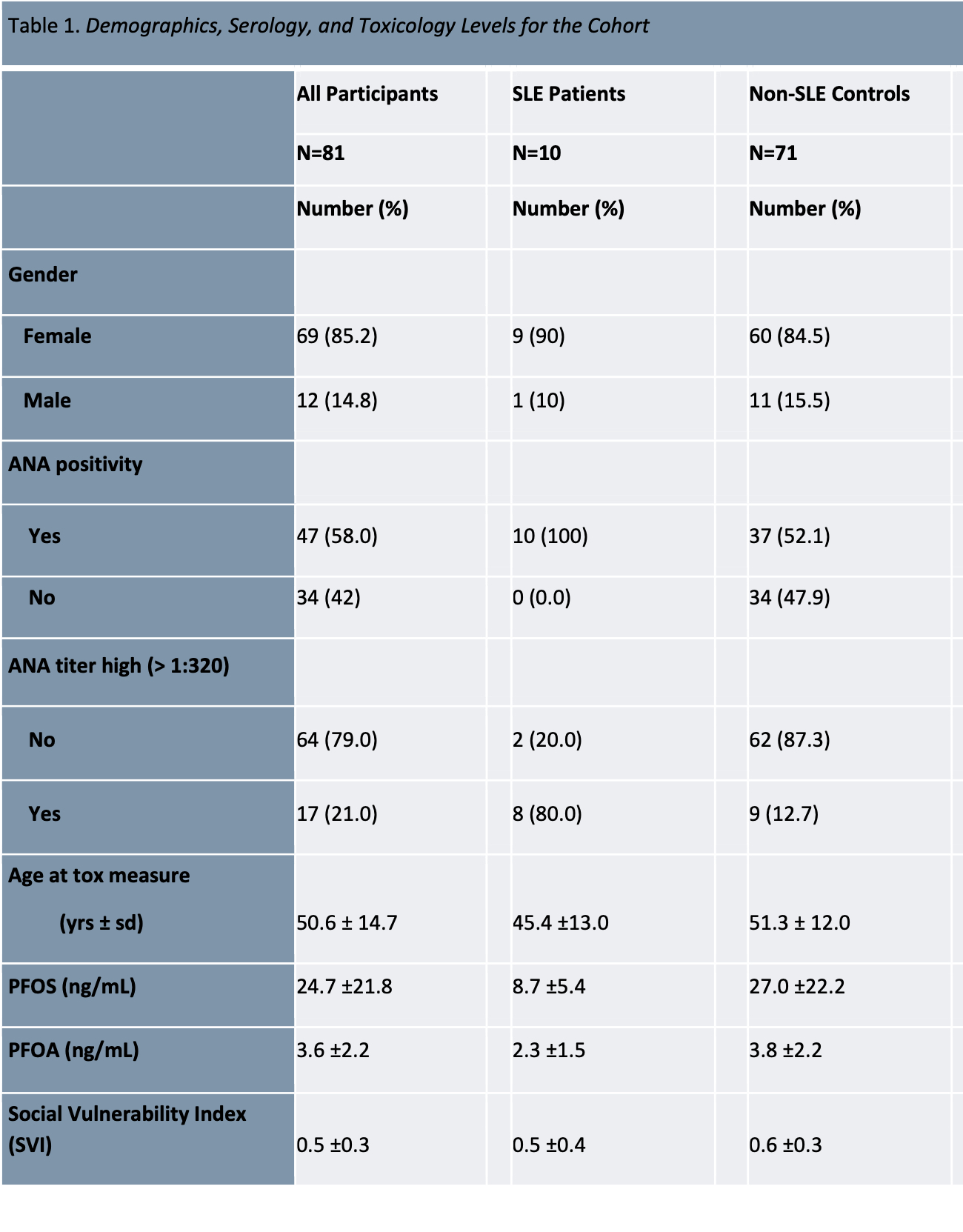

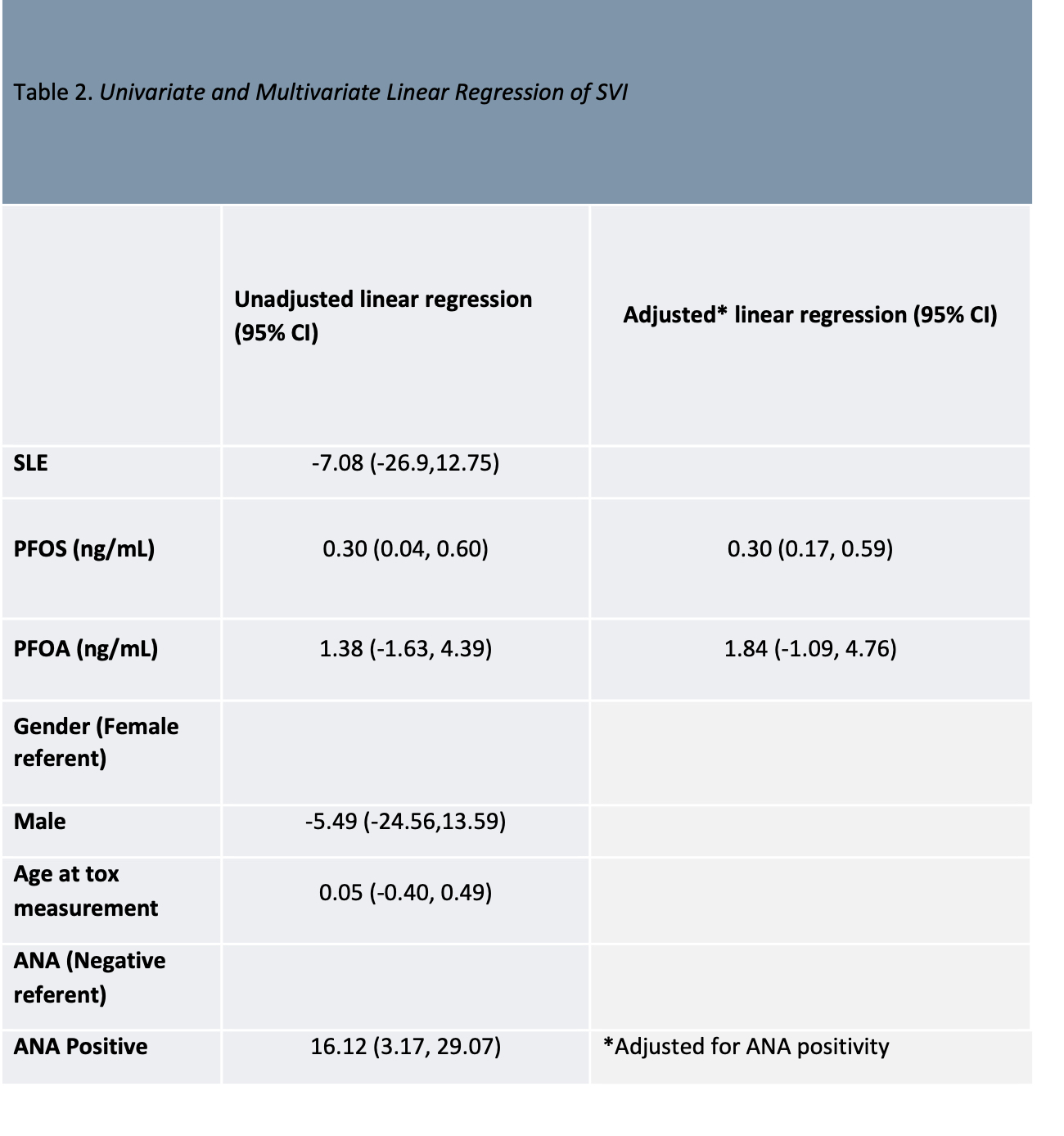

Results: A total of 81 participants, including 10 patients with SLE and 71 non-SLE controls were evaluated. All were non-Hispanic black, 85% female and 15% male (Table 1). In the linear regression modeling, participants with PFOS exposure had a small increase (worsening) in SVI for every one unit increase in the serum PFOS concentration (median PFOS concentration 24.7 ng/mL) (0.30; 95% CI=0.04,0.60). SVI was not significantly associated with PFOA exposure (median PFOA concentration 3.6 ng/mL), (1.38; 95% CI=-1.63,4.39). Participants with a positive ANA had a statistically significant increase in mean SVI (16.1; 95% CI 3.17, 29.07) compared to those with a negative ANA. There was no significant difference in SVI between patients with SLE and controls (-7.1; 95% CI= -26.9,12.75), by age (0.05; 95% CI=-0.4, 0.49) or gender (-5.49; 95% CI=-25.6, 13.6). Adjusting for positive ANA, the association between PFOS exposure and SVI remained significant, albeit small, (0.3; 95% CI=0.17, 0.59) and there remained no significant association between SVI and PFOA (1.84; 95% CI= -1.09, 4.76) (Table 2).

Conclusion: In our study of African Americans with and without SLE, PFOS, but not PFOA, exposure was associated with higher social vulnerability measured by the SVI after adjustment for ANA positivity. SLE diagnosis was not associated with higher social vulnerability, possibly due to the small number of participants with SLE. These findings support continued studies of PFAS and other environmental contaminants which are associated with disparities in exposure, putting vulnerable communities at risk for adverse health impacts such as SLE.

Table 1. Demographics, serology, and toxiciology levels of participants.

Table 1. Demographics, serology, and toxiciology levels of participants.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis.

.jpg) Figure 1. Box and whisker plots showing (a) PFOS by gender and ANA positivity for controls, (b) PFOA by gender and ANA positivity for controls, and (c) SVI by gender and ANA positivity for controls.

Figure 1. Box and whisker plots showing (a) PFOS by gender and ANA positivity for controls, (b) PFOA by gender and ANA positivity for controls, and (c) SVI by gender and ANA positivity for controls.

Disclosures: E. Vara, None; D. Wilson, None; J. Pearce, None; J. Oates, None; D. Kamen, None.

Background/Purpose: Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a class of persistent organic pollutants found in nonstick products, water repellant fabrics, fire-retardant foams, and food packaging. Highly stable, the compounds persist in soil and water, bioaccumulate, and are found in the blood and tissues of animals and humans. Several PFAS, including perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), have been associated with negative health effects through hormone disruption and immunologic dysfunction.

This ongoing study explores the associations between PFAS biomarkers, autoimmunity, and neighborhood-level social determinants of health among African Americans participating in a population-based cohort study.

Methods: Data was utilized from a longitudinal study of Gullah African American patients with SLE and non-SLE controls. Demographics, medical history, Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) (incorporating socioeconomic status, household composition, race/ethnicity/language, and housing/transportation), antinuclear antibody (ANA) status and titer, serum PFOA concentration (ng/mL), and serum PFOS concentration (ng/ml) from in-person visits from 2003-2019 were included. Spatial overlays were applied to assign census tract identifiers and obtain SVI data for the participants. Statistical analysis using univariate and multivariate linear regression was performed.

Results: A total of 81 participants, including 10 patients with SLE and 71 non-SLE controls were evaluated. All were non-Hispanic black, 85% female and 15% male (Table 1). In the linear regression modeling, participants with PFOS exposure had a small increase (worsening) in SVI for every one unit increase in the serum PFOS concentration (median PFOS concentration 24.7 ng/mL) (0.30; 95% CI=0.04,0.60). SVI was not significantly associated with PFOA exposure (median PFOA concentration 3.6 ng/mL), (1.38; 95% CI=-1.63,4.39). Participants with a positive ANA had a statistically significant increase in mean SVI (16.1; 95% CI 3.17, 29.07) compared to those with a negative ANA. There was no significant difference in SVI between patients with SLE and controls (-7.1; 95% CI= -26.9,12.75), by age (0.05; 95% CI=-0.4, 0.49) or gender (-5.49; 95% CI=-25.6, 13.6). Adjusting for positive ANA, the association between PFOS exposure and SVI remained significant, albeit small, (0.3; 95% CI=0.17, 0.59) and there remained no significant association between SVI and PFOA (1.84; 95% CI= -1.09, 4.76) (Table 2).

Conclusion: In our study of African Americans with and without SLE, PFOS, but not PFOA, exposure was associated with higher social vulnerability measured by the SVI after adjustment for ANA positivity. SLE diagnosis was not associated with higher social vulnerability, possibly due to the small number of participants with SLE. These findings support continued studies of PFAS and other environmental contaminants which are associated with disparities in exposure, putting vulnerable communities at risk for adverse health impacts such as SLE.

Table 1. Demographics, serology, and toxiciology levels of participants.

Table 1. Demographics, serology, and toxiciology levels of participants. Table 2. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis.

Table 2. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analysis..jpg) Figure 1. Box and whisker plots showing (a) PFOS by gender and ANA positivity for controls, (b) PFOA by gender and ANA positivity for controls, and (c) SVI by gender and ANA positivity for controls.

Figure 1. Box and whisker plots showing (a) PFOS by gender and ANA positivity for controls, (b) PFOA by gender and ANA positivity for controls, and (c) SVI by gender and ANA positivity for controls.Disclosures: E. Vara, None; D. Wilson, None; J. Pearce, None; J. Oates, None; D. Kamen, None.