Back

Poster Session B

Epidemiology, health policy and outcomes

Session: (0695–0723) Epidemiology and Public Health Poster I

0716: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms in Systemic Autoimmune Rheumatic Disease Patients During the Early COVID-19 Pandemic

Sunday, November 13, 2022

9:00 AM – 10:30 AM Eastern Time

Location: Virtual Poster Hall

- JE

Jack Ellrodt, BA

Williams College

Brookline, MA, United States

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Jack Ellrodt1, Emily G Oakes1, Laura Kubzansky2, Karestan Koenen2, Hongshu Guan1 and Karen Costenbader1, 1Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA, 2Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA

Background/Purpose: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a complex psychiatric disorder that can result from experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event, such as an accident, assault, or death. We aimed to assess the prevalence of PTSD symptoms at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic among individuals with or without systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease (SARD) diagnoses, given the increased stress those with SARDs may have experienced given their immunosuppression.

Methods: In May 2020, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, we invited 6,681 patients of a large multihospital system who had opted in to research opportunities (including 378 with ≥ 2 ICD 9/10 prior PTSD codes) to complete the Brief Trauma Questionnaire and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5). The Brief Trauma Questionnaire and the PCL-5 are previously validated questionnaires that can identify individuals with probable PTSD. Diagnoses for prior PSTD, SARD, anxiety, depression, and adjustment disorders were identified using ICD-9/10 billing code algorithms. Survey responses were analyzed using univariable t-tests to identify differences between SARDs and non-SARDs subjects. We used multivariable logistic regression to identify potential predictors of PCL-5 positivity, an indication for PTSD, at the time of survey distribution.

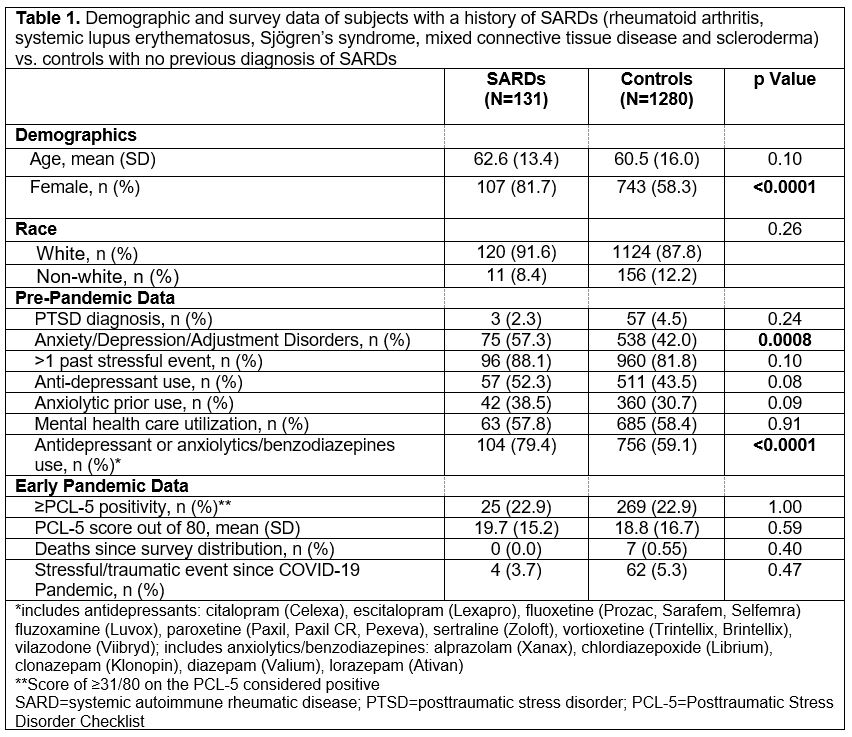

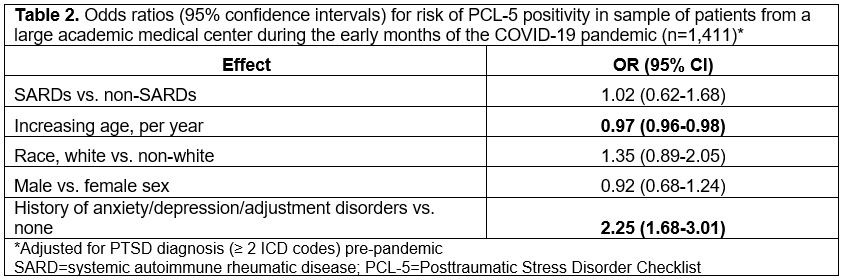

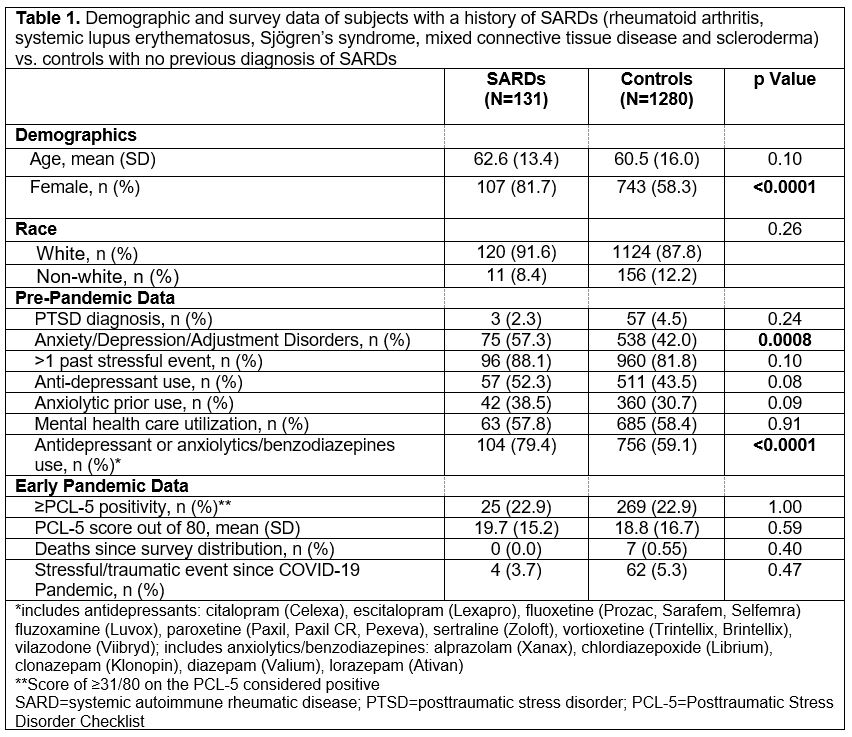

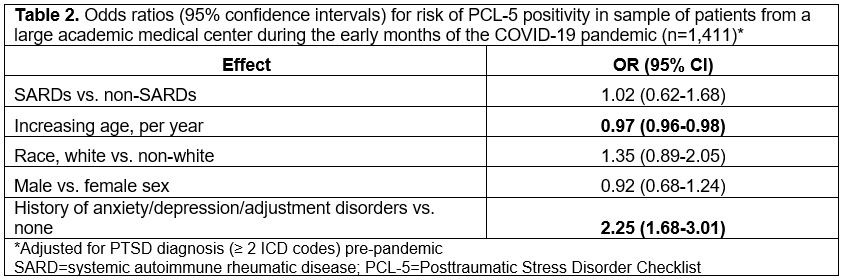

Results: We received 1,411 complete and unique responses (21% response rate) between 5/2020 and 9/2021, with most responses received in late May to early June 2020. Of these respondents, 60 had a history of PTSD prior to the pandemic and 131 had a prior history of a SARD (Table 1). In the univariable analysis, the SARDs population was significantly more female (p< 0.0001) and had a higher baseline prevalence of anxiety, depression, and adjustment disorders (p=0.0008) than respondents without SARDs. In the early pandemic, there were no significant differences in PCL-5 scores (p=0.59), PCL-5 positivity (p=1.00), or traumatic events (p=0.47) between those with and without a SARDs diagnosis. Upon adjusting for pre-pandemic PTSD diagnoses, we found younger age (OR=0.97, 95% CI [0.96, 0.98] per increasing year) and history of anxiety, depression, or adjustment disorder (OR=2.25, 95% CI [1.68, 3.01]) to be the most significant predictors of PCL-5 positivity during the early pandemic (Table 2).

Conclusion: While SARDs was not a significant predictor of new onset PTSD symptoms, we found that younger individuals and those with a history of baseline anxiety, depression, or adjustment disorders, which were more common pre-pandemic among those with SARDs, were more likely to screen positive on the PCL-5 during early COVID-19 pandemic. The lack of increased PTSD symptoms in SARDs vs. non-SARDs populations suggests that during the early months of the pandemic, SARDs patients may not have been at higher risk for new PTSD symptoms.

Disclosures: J. Ellrodt, None; E. Oakes, None; L. Kubzansky, None; K. Koenen, None; H. Guan, None; K. Costenbader, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Amgen, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, GlaxoSmithKline(GSK), Gilead, Exagen, Neutrolis, Cel-Sci, Alkermes.

Background/Purpose: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a complex psychiatric disorder that can result from experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event, such as an accident, assault, or death. We aimed to assess the prevalence of PTSD symptoms at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic among individuals with or without systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease (SARD) diagnoses, given the increased stress those with SARDs may have experienced given their immunosuppression.

Methods: In May 2020, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, we invited 6,681 patients of a large multihospital system who had opted in to research opportunities (including 378 with ≥ 2 ICD 9/10 prior PTSD codes) to complete the Brief Trauma Questionnaire and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL-5). The Brief Trauma Questionnaire and the PCL-5 are previously validated questionnaires that can identify individuals with probable PTSD. Diagnoses for prior PSTD, SARD, anxiety, depression, and adjustment disorders were identified using ICD-9/10 billing code algorithms. Survey responses were analyzed using univariable t-tests to identify differences between SARDs and non-SARDs subjects. We used multivariable logistic regression to identify potential predictors of PCL-5 positivity, an indication for PTSD, at the time of survey distribution.

Results: We received 1,411 complete and unique responses (21% response rate) between 5/2020 and 9/2021, with most responses received in late May to early June 2020. Of these respondents, 60 had a history of PTSD prior to the pandemic and 131 had a prior history of a SARD (Table 1). In the univariable analysis, the SARDs population was significantly more female (p< 0.0001) and had a higher baseline prevalence of anxiety, depression, and adjustment disorders (p=0.0008) than respondents without SARDs. In the early pandemic, there were no significant differences in PCL-5 scores (p=0.59), PCL-5 positivity (p=1.00), or traumatic events (p=0.47) between those with and without a SARDs diagnosis. Upon adjusting for pre-pandemic PTSD diagnoses, we found younger age (OR=0.97, 95% CI [0.96, 0.98] per increasing year) and history of anxiety, depression, or adjustment disorder (OR=2.25, 95% CI [1.68, 3.01]) to be the most significant predictors of PCL-5 positivity during the early pandemic (Table 2).

Conclusion: While SARDs was not a significant predictor of new onset PTSD symptoms, we found that younger individuals and those with a history of baseline anxiety, depression, or adjustment disorders, which were more common pre-pandemic among those with SARDs, were more likely to screen positive on the PCL-5 during early COVID-19 pandemic. The lack of increased PTSD symptoms in SARDs vs. non-SARDs populations suggests that during the early months of the pandemic, SARDs patients may not have been at higher risk for new PTSD symptoms.

Disclosures: J. Ellrodt, None; E. Oakes, None; L. Kubzansky, None; K. Koenen, None; H. Guan, None; K. Costenbader, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Amgen, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, GlaxoSmithKline(GSK), Gilead, Exagen, Neutrolis, Cel-Sci, Alkermes.