Back

Poster Session A

Diversity, inclusion and racial disparities

Session: (0085–0122) Healthcare Disparities in Rheumatology Poster

0110: Does Access Reduce Excess Use? Lupus Outcomes in Two Distinct Socioeconomic Groups Seen by University Rheumatologists

Saturday, November 12, 2022

1:00 PM – 3:00 PM Eastern Time

Location: Virtual Poster Hall

- AC

Alissa Chandler, MD, BS

Washington University

St. Louis, MO, United States

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Alissa Chandler1, Rodney Tehrani1 and Varun Bhalla2, 1Loyola University Medical Center, Maywood, IL, 2Loyola University Medical cneter, Chicago, IL

Background/Purpose: SLE is a multi-organ chronic autoimmune disease, which requires chronic medication use and close follow up with a rheumatologist. Poor disease control can lead to end organ damage and increased morbidity and mortality. Poor outcomes of SLE are increased in minority ethnic groups and there is evidence of increased rates of complications in patients with a lower socioeconomic status (SES), independent of race (1). Access and proximity to quality rheumatologists is one possible way to improve outcomes. Our goal is to analyze the difference in healthcare use and outcomes in two distinct SES groups of SLE patients that are seen by the same academic rheumatologists.

Methods: This was a retrospective review of patients with SLE based on ICD 9/10 coding, seen by academic rheumatologists at its various clinic sites. Patients included were at least 18 years old and had at least three clinic visits from 2015-2020. All patients lived in zip codes based on income cutoffs. High SES group lived in zip codes with median household income >$85,000 based on US Census data. Low SES group lived in zip codes with median household income < $55,000. All zip codes were within a 30-minute drive of clinic sites. Data including demographics, comorbidities and treatment history were collected from the electronic medical record. Outcomes of emergency room visits, hospital admissions, steroid use, missed appointments, and distance traveled to clinic were compared by paired student T test. In addition, regression models were performed for certain variables.

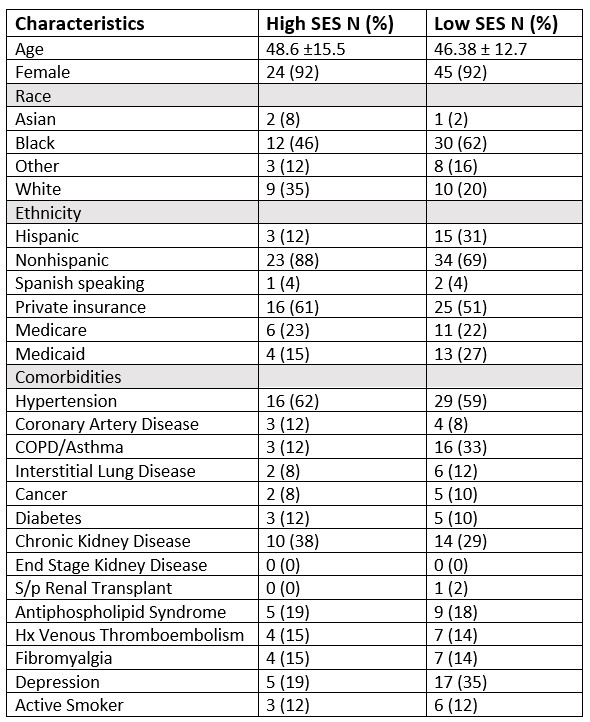

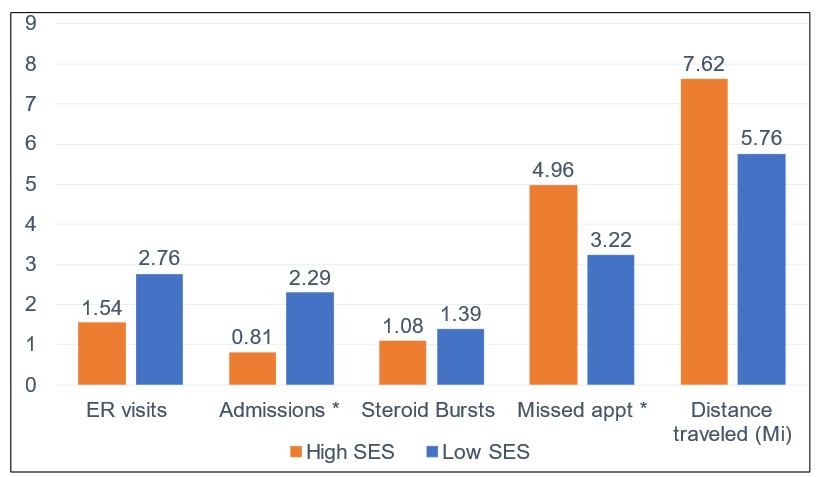

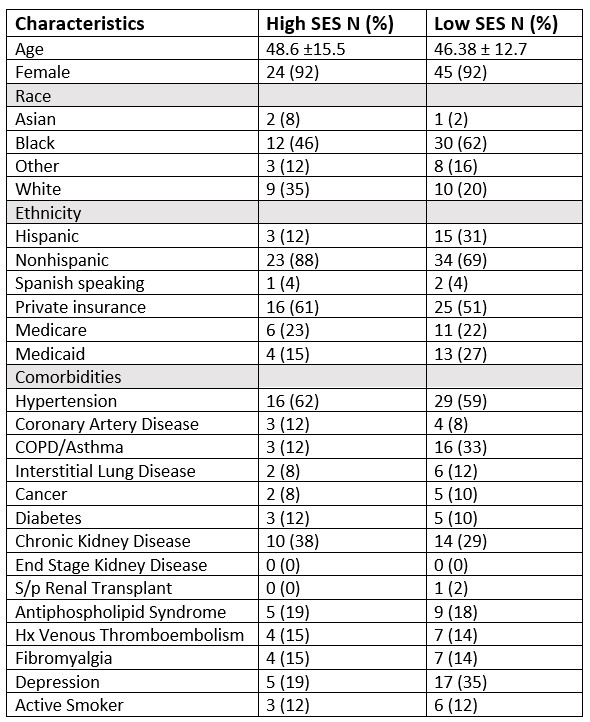

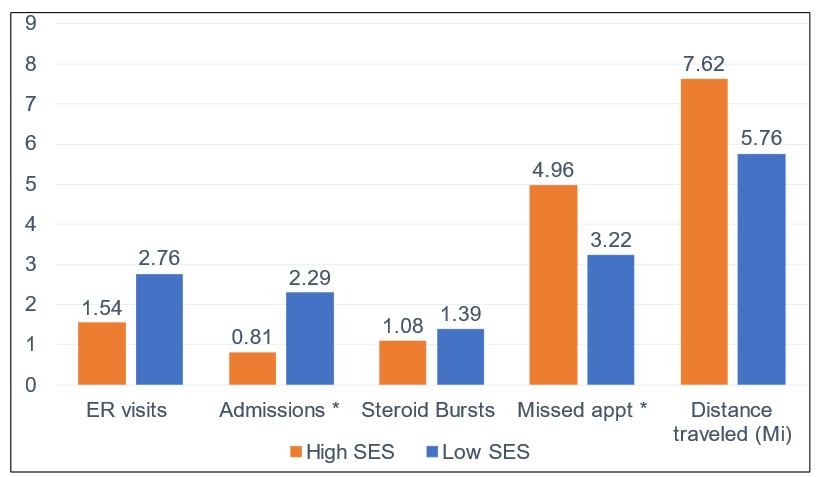

Results: Low SES group had 49 patients and high SES group had 26 patients. The range of median incomes in high SES group was $86,623 - $174,760 with a mean of $109,014. In low SES group, median income ranged from $26,900 - $56,618 with mean of $50,139. Demographics and comorbidities of each group are shown in Table 1. The only significant difference in comorbidities were rate of COPD/Asthma (p=0.045). The most common SLE organ involvement in each group were skin, joints, and hematologic. There were statistically significant higher admission rates in low SES group and more missed appts in high SES group. Statistical significance not reached for other outcomes (Fig 1). Regression models for variables of SES, Hispanic ethnicity, Medicaid use, depression and chronic steroid use were performed. There were no significant confounders identified, however Medicaid use trended towards significance. Subgroup analysis of Medicaid patients showed mean ER visits 3.76 vs 1.91 in non-Medicaid (p=0.04) and mean steroid burst 2.18 vs. 1.02 in non-Medicaid (p=0.013). There were no significant differences in HCQ use, decrease in renal function, or death during study period between each group.

Conclusion: Though there are differences in the variables analyzed, most are not statistically significant. A larger study population may help elucidate whether access and proximity to a rheumatologist can help control for higher healthcare and steroid use in a lower SES population. Medicaid status appears to be a significant variable, and could be used to identify patients that will utilize the emergency room and steroids more frequently than a non-Medicaid population.

Table 1: Demographics and comorbidities of each group.

Table 1: Demographics and comorbidities of each group.

Figure 1: Mean values of primary and secondary outcomes and comparison with T test. Mean (standard deviation) for high SES and low SES respectively: ER visits 1.54 (2.06), 2.76 (3.72), Admissions 0.81 (1.06), 2.29 (3.54), Steroid bursts 1.08 (2.04), 1.39 (1.53), Missed appt 4.96 (4.91), 3.22 (2.53), Distance 7.62 (6.02), 5.76 (5.35).

Figure 1: Mean values of primary and secondary outcomes and comparison with T test. Mean (standard deviation) for high SES and low SES respectively: ER visits 1.54 (2.06), 2.76 (3.72), Admissions 0.81 (1.06), 2.29 (3.54), Steroid bursts 1.08 (2.04), 1.39 (1.53), Missed appt 4.96 (4.91), 3.22 (2.53), Distance 7.62 (6.02), 5.76 (5.35).

Disclosures: A. Chandler, None; R. Tehrani, None; V. Bhalla, None.

Background/Purpose: SLE is a multi-organ chronic autoimmune disease, which requires chronic medication use and close follow up with a rheumatologist. Poor disease control can lead to end organ damage and increased morbidity and mortality. Poor outcomes of SLE are increased in minority ethnic groups and there is evidence of increased rates of complications in patients with a lower socioeconomic status (SES), independent of race (1). Access and proximity to quality rheumatologists is one possible way to improve outcomes. Our goal is to analyze the difference in healthcare use and outcomes in two distinct SES groups of SLE patients that are seen by the same academic rheumatologists.

Methods: This was a retrospective review of patients with SLE based on ICD 9/10 coding, seen by academic rheumatologists at its various clinic sites. Patients included were at least 18 years old and had at least three clinic visits from 2015-2020. All patients lived in zip codes based on income cutoffs. High SES group lived in zip codes with median household income >$85,000 based on US Census data. Low SES group lived in zip codes with median household income < $55,000. All zip codes were within a 30-minute drive of clinic sites. Data including demographics, comorbidities and treatment history were collected from the electronic medical record. Outcomes of emergency room visits, hospital admissions, steroid use, missed appointments, and distance traveled to clinic were compared by paired student T test. In addition, regression models were performed for certain variables.

Results: Low SES group had 49 patients and high SES group had 26 patients. The range of median incomes in high SES group was $86,623 - $174,760 with a mean of $109,014. In low SES group, median income ranged from $26,900 - $56,618 with mean of $50,139. Demographics and comorbidities of each group are shown in Table 1. The only significant difference in comorbidities were rate of COPD/Asthma (p=0.045). The most common SLE organ involvement in each group were skin, joints, and hematologic. There were statistically significant higher admission rates in low SES group and more missed appts in high SES group. Statistical significance not reached for other outcomes (Fig 1). Regression models for variables of SES, Hispanic ethnicity, Medicaid use, depression and chronic steroid use were performed. There were no significant confounders identified, however Medicaid use trended towards significance. Subgroup analysis of Medicaid patients showed mean ER visits 3.76 vs 1.91 in non-Medicaid (p=0.04) and mean steroid burst 2.18 vs. 1.02 in non-Medicaid (p=0.013). There were no significant differences in HCQ use, decrease in renal function, or death during study period between each group.

Conclusion: Though there are differences in the variables analyzed, most are not statistically significant. A larger study population may help elucidate whether access and proximity to a rheumatologist can help control for higher healthcare and steroid use in a lower SES population. Medicaid status appears to be a significant variable, and could be used to identify patients that will utilize the emergency room and steroids more frequently than a non-Medicaid population.

Table 1: Demographics and comorbidities of each group.

Table 1: Demographics and comorbidities of each group.  Figure 1: Mean values of primary and secondary outcomes and comparison with T test. Mean (standard deviation) for high SES and low SES respectively: ER visits 1.54 (2.06), 2.76 (3.72), Admissions 0.81 (1.06), 2.29 (3.54), Steroid bursts 1.08 (2.04), 1.39 (1.53), Missed appt 4.96 (4.91), 3.22 (2.53), Distance 7.62 (6.02), 5.76 (5.35).

Figure 1: Mean values of primary and secondary outcomes and comparison with T test. Mean (standard deviation) for high SES and low SES respectively: ER visits 1.54 (2.06), 2.76 (3.72), Admissions 0.81 (1.06), 2.29 (3.54), Steroid bursts 1.08 (2.04), 1.39 (1.53), Missed appt 4.96 (4.91), 3.22 (2.53), Distance 7.62 (6.02), 5.76 (5.35).Disclosures: A. Chandler, None; R. Tehrani, None; V. Bhalla, None.