Back

Poster Session C

Epidemiology, health policy and outcomes

Session: (1267–1303) Measures and Measurement of Healthcare Quality Poster

1277: Improving Patient Appropriate Osteoporosis Screening with Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry Scans in an Academic Internal Medicine Practice

Sunday, November 13, 2022

1:00 PM – 3:00 PM Eastern Time

Location: Virtual Poster Hall

- NP

Nithin Pusapati, MD

Rush University Medical Center

Chicago, IL, United States

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Nithin Pusapati1, Rebecca Fitzpatrick1, Manya Gupta1 and Sonali Khandelwal2, 1Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, 2Rush University, Chicago, IL

Background/Purpose: Nearly 53.6 million people in America have osteoporosis with increasing incidence each year (Brauer, JAMA 2009). Almost 25% of people with a hip fracture die within 1 year of the fracture (Wright, Journal Bone Mineral Research 2014). Currently, screening for osteoporosis is recommended for women over the age of 65 or over 50 with noted risk factors. Bisphosphonate therapy has been shown to reduce both fracture risk and mortality in people with osteoporosis. (Brauer, JAMA 2009). Primary care settings are often the first line opportunity to provide appropriate screening measures to adult patients. Our project aims to both identify and improve the frequency of osteoporosis screening by providers in an Internal Medicine practice, as well as to increase comfort with treatment.

Methods: An initial survey was sent to a large urban academic practice of Internal Medicine residents and attendings to determine current practice and attitudes toward osteoporosis screening and management. After the initial survey, a lecture on osteoporosis screening indications, diagnosis, and general management was delivered to physicians in the same practice. A repeat survey was sent to assess the effectiveness of the educational material. Qualitative statistics were used to analyze the data. A p-value of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

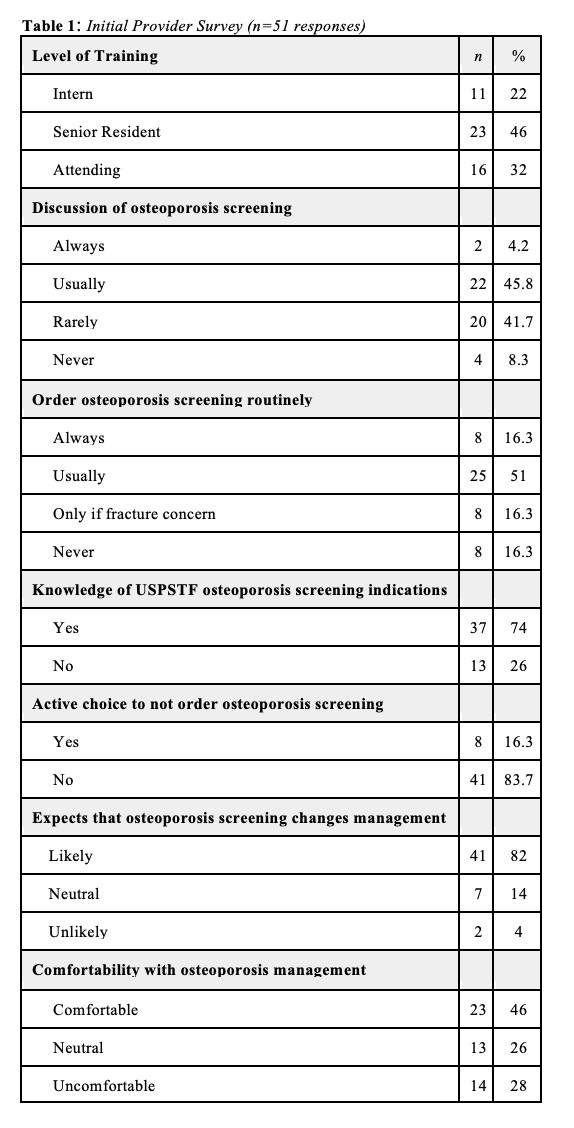

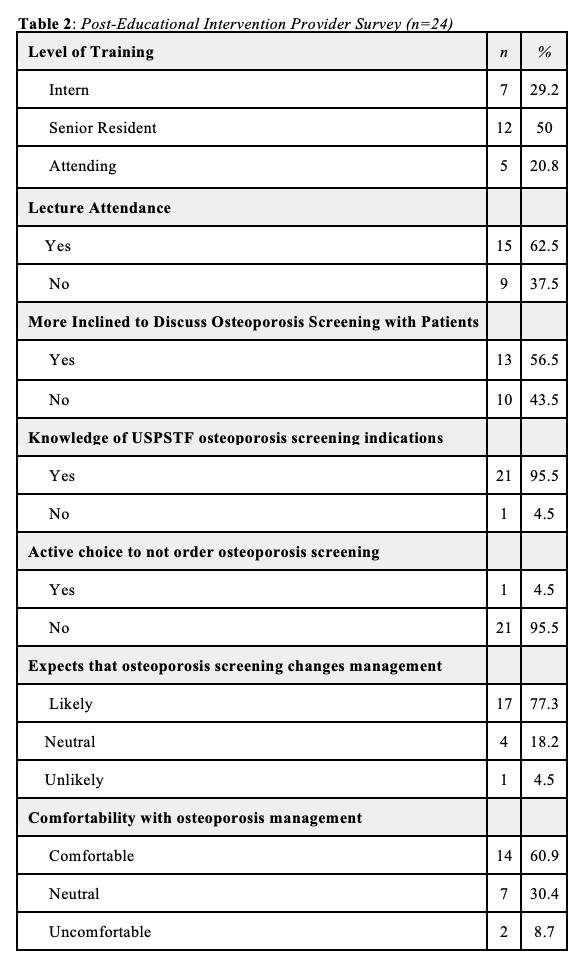

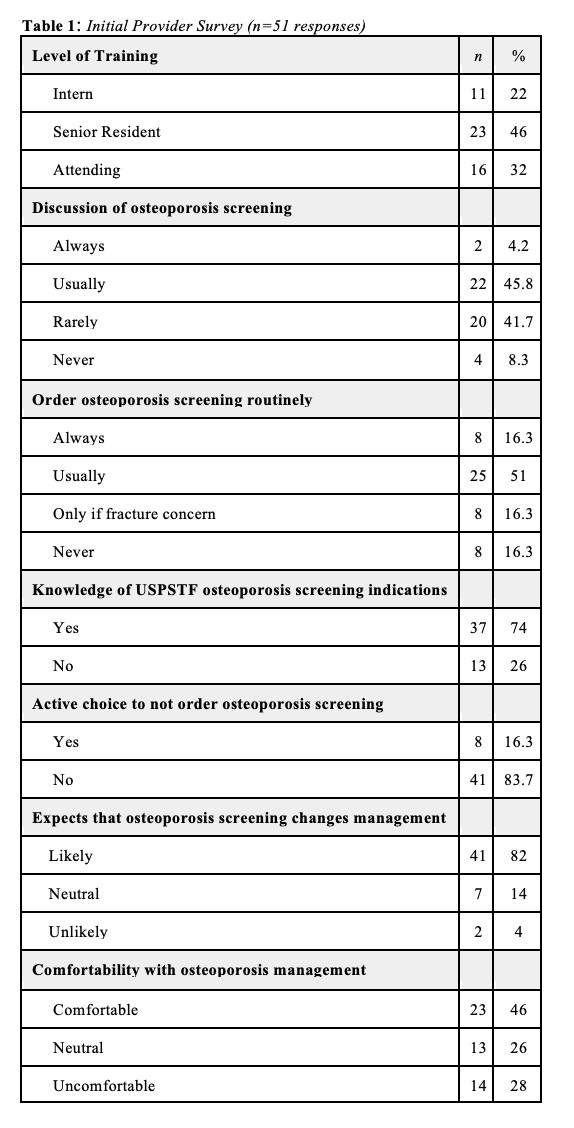

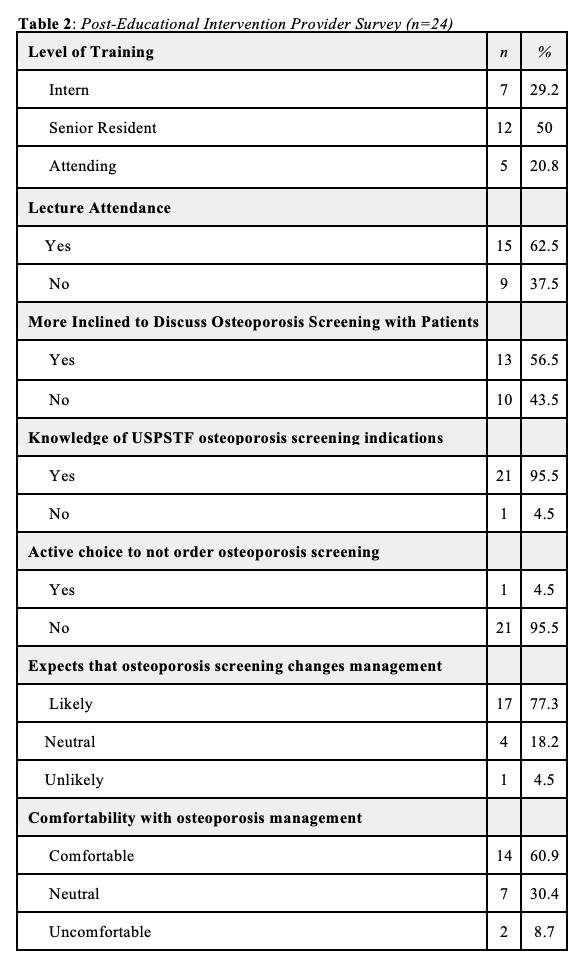

Results: A total of 51 providers completed the initial survey. Their demographics and responses to osteoporosis screening and management are in Table 1. Roughly half of providers "rarely/never" discussed osteoporosis screening with patients. Nearly 67% of providers stated that they "usually/always" order osteoporosis screening; 74% of providers knew the indications for osteoporosis screening. A majority (82%) of providers, thought that screening would change their management. Forty-six percent of providers were comfortable with osteoporosis management. After the educational material/intervention, another survey was sent and 24 providers responded, with results noted in Table 2. After the education, 56% of providers were likely to discuss osteoporosis screening (p=0.7). 96% stated they knew the indications for screening (p=0.03). There was also a large increase of providers who felt comfortable with osteoporosis management (60.9%) post-lecture (p=0.2).

Conclusion: In an academic Internal Medicine practice of physicians, a dedicated lecture on osteoporosis improved both knowledge about osteoporosis screening indications, diagnosis and management, and provider willingness to discuss osteoporosis screening with their patients. This project demonstrated that, at minimum, a traditional lecture format reliably improved provider knowledge of screening guidelines and should be incorporated into medical educational curricula. A more structured, targeted Rheumatology focused educational series may be even more impactful. As such, further research is necessary to determine if these interventions translate to improved bone health outcomes and if additional educational interventions can continue to increase Internists' comfort with the management of bone loss.

Table 1 notes the results of the survey sent to Internal Medicine residents and attendings regarding their practice of osteoporosis screening and management prior to the educational intervention.

Table 1 notes the results of the survey sent to Internal Medicine residents and attendings regarding their practice of osteoporosis screening and management prior to the educational intervention.

Table 2 notes the results of the survey sent to Internal Medicine residents and attendings regarding their practice of osteoporosis screening and management after the educational intervention.

Table 2 notes the results of the survey sent to Internal Medicine residents and attendings regarding their practice of osteoporosis screening and management after the educational intervention.

Disclosures: N. Pusapati, None; R. Fitzpatrick, None; M. Gupta, None; S. Khandelwal, None.

Background/Purpose: Nearly 53.6 million people in America have osteoporosis with increasing incidence each year (Brauer, JAMA 2009). Almost 25% of people with a hip fracture die within 1 year of the fracture (Wright, Journal Bone Mineral Research 2014). Currently, screening for osteoporosis is recommended for women over the age of 65 or over 50 with noted risk factors. Bisphosphonate therapy has been shown to reduce both fracture risk and mortality in people with osteoporosis. (Brauer, JAMA 2009). Primary care settings are often the first line opportunity to provide appropriate screening measures to adult patients. Our project aims to both identify and improve the frequency of osteoporosis screening by providers in an Internal Medicine practice, as well as to increase comfort with treatment.

Methods: An initial survey was sent to a large urban academic practice of Internal Medicine residents and attendings to determine current practice and attitudes toward osteoporosis screening and management. After the initial survey, a lecture on osteoporosis screening indications, diagnosis, and general management was delivered to physicians in the same practice. A repeat survey was sent to assess the effectiveness of the educational material. Qualitative statistics were used to analyze the data. A p-value of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results: A total of 51 providers completed the initial survey. Their demographics and responses to osteoporosis screening and management are in Table 1. Roughly half of providers "rarely/never" discussed osteoporosis screening with patients. Nearly 67% of providers stated that they "usually/always" order osteoporosis screening; 74% of providers knew the indications for osteoporosis screening. A majority (82%) of providers, thought that screening would change their management. Forty-six percent of providers were comfortable with osteoporosis management. After the educational material/intervention, another survey was sent and 24 providers responded, with results noted in Table 2. After the education, 56% of providers were likely to discuss osteoporosis screening (p=0.7). 96% stated they knew the indications for screening (p=0.03). There was also a large increase of providers who felt comfortable with osteoporosis management (60.9%) post-lecture (p=0.2).

Conclusion: In an academic Internal Medicine practice of physicians, a dedicated lecture on osteoporosis improved both knowledge about osteoporosis screening indications, diagnosis and management, and provider willingness to discuss osteoporosis screening with their patients. This project demonstrated that, at minimum, a traditional lecture format reliably improved provider knowledge of screening guidelines and should be incorporated into medical educational curricula. A more structured, targeted Rheumatology focused educational series may be even more impactful. As such, further research is necessary to determine if these interventions translate to improved bone health outcomes and if additional educational interventions can continue to increase Internists' comfort with the management of bone loss.

Table 1 notes the results of the survey sent to Internal Medicine residents and attendings regarding their practice of osteoporosis screening and management prior to the educational intervention.

Table 1 notes the results of the survey sent to Internal Medicine residents and attendings regarding their practice of osteoporosis screening and management prior to the educational intervention.  Table 2 notes the results of the survey sent to Internal Medicine residents and attendings regarding their practice of osteoporosis screening and management after the educational intervention.

Table 2 notes the results of the survey sent to Internal Medicine residents and attendings regarding their practice of osteoporosis screening and management after the educational intervention. Disclosures: N. Pusapati, None; R. Fitzpatrick, None; M. Gupta, None; S. Khandelwal, None.