Back

Poster Session C

Pediatric autoimmune diseases: Kawasaki disease, juvenile dermatomyositis and juvenile localized scleroderma

Session: (1360–1386) Pediatric Rheumatology – Clinical Poster II: Connective Tissue Disease

1382: Juvenile Eosinophilic Fasciitis: A Single-Center Cohort

Sunday, November 13, 2022

1:00 PM – 3:00 PM Eastern Time

Location: Virtual Poster Hall

Leigh Stubbs, MD, MPH

Baylor College of Medicine

Houston, TX, United States

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Leigh Stubbs1, Oluwaseun Ogunbona2, Adekunle Adesina1, Sara Anvari1, Emily Beil1, Jamie Lai1, Andrea Ramirez1, Vibha Szafron1, Matthew Ditzler1 and Marietta DeGuzman1, 1Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, 2Houston Methodist Hospital, Houston, TX

Background/Purpose: Eosinophilic fasciitis (EF) is a rare fibrosing disease. Since described in 1975, less than 30 pediatric cases have been reported. EF presents with painful swelling and progressive skin induration causing peau d' orange appearance and the groove sign. Laboratory findings include elevated inflammatory markers, aldolase, eosinophils, and immunoglobulin G. EF diagnosis requires biopsy or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) indicating fasciitis. Risk factors for treatment resistance include concurrent morphea and pediatric age of onset. As triggers, presentation, treatment, and course often differ between pediatric and adult patients, it is important to further characterize juvenile EF cohorts.

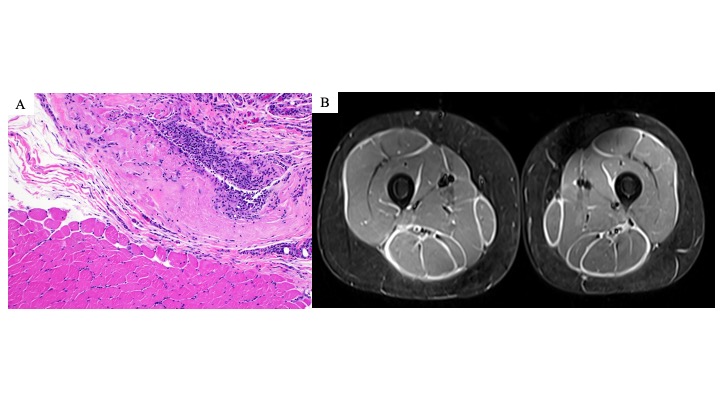

Methods: We report the demographics, clinical findings, pathology, MRIs, treatment, and outcomes for six patients with juvenile EF. A retrospective chart review was performed for all patients diagnosed with EF at our institution between November 2011- May 2022. Inclusion criteria included age at diagnosis < 18 years as well as EF confirmation by histology and MRI (Figure 1).

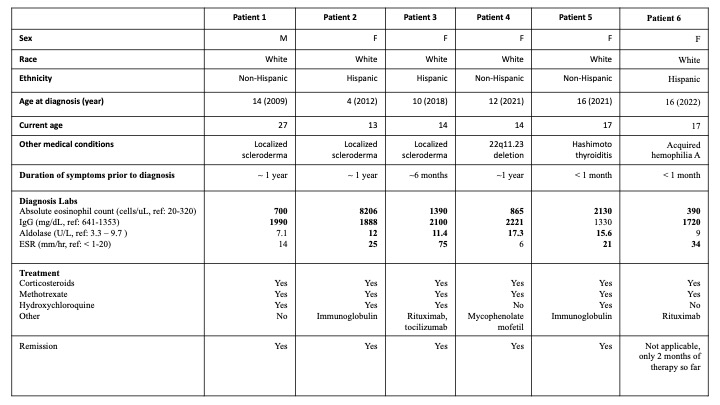

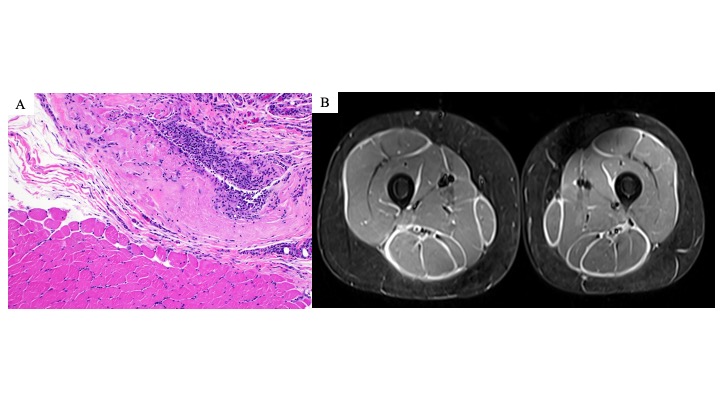

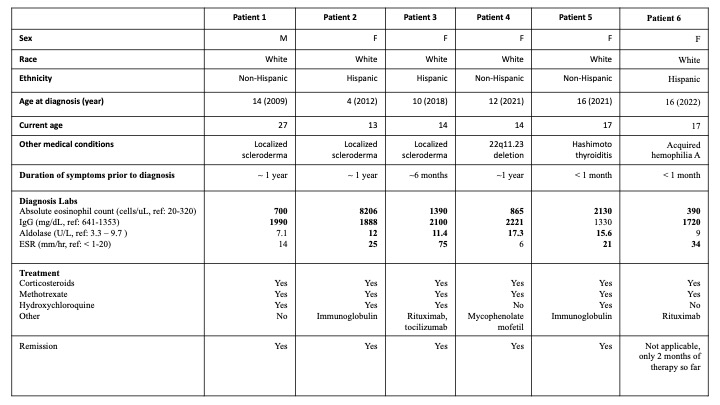

Results: For our juvenile EF cohort, the majority were female (83%) (Table 1). There were 50% Hispanic and 50% non-Hispanic patients. Age at diagnosis ranged from 4-16 years (median: 13) with associated follow-up ranging from 2 months to 12 years. Duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis ranged from 1 month to 1 year (median: 9 months). Associated medical conditions included localized scleroderma (50%), Hashimoto's thyroiditis, 22q11 deletion, and acquired hemophilia A. Most patients presented with bilateral, progressive painful swelling and severe joint limitation mostly without any positive skin findings; one patient presented with unilateral involvement. All patients presented with a positive prayer sign (Figure 2). Initial treatment included corticosteroids and methotrexate. Other medications included hydroxychloroquine, immunoglobulin, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab, and tocilizumab. Two patients had relapse of both morphea and fasciitis. Now, 83% are in remission with the remaining patient with resolved musculoskeletal symptoms and an improving factor 8 level after 2 months of treatment.

Conclusion: Juvenile EF can present with swelling and progressive induration without skin abnormalities. Unlike adult cohorts, there were no underlying malignancies or associations with significant trauma. Previous juvenile EF cohorts have described systemic involvement (hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy), which was not present within this cohort. Although non-specific, the prayer sign could be a helpful clinical finding to identify juvenile EF leading to early recognition and preventing long-term disabling outcomes.

Figure 1. Examples of eosinophilic fasciitis pathology and MRI findings. (A) Left lower leg muscle and fascia biopsy from patient 4 consistent with eosinophilic fasciitis. Hematoxylin and eosin (H &E) section (magnification, x100) showing fascia with underlying muscle. The fascia shows thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration (many macrophages and lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and rare eosinophils). (B) MRI bilateral thighs with and without contrast of patient 4 demonstrating extensive, symmetric fasciitis on STIR axial image.

Figure 1. Examples of eosinophilic fasciitis pathology and MRI findings. (A) Left lower leg muscle and fascia biopsy from patient 4 consistent with eosinophilic fasciitis. Hematoxylin and eosin (H &E) section (magnification, x100) showing fascia with underlying muscle. The fascia shows thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration (many macrophages and lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and rare eosinophils). (B) MRI bilateral thighs with and without contrast of patient 4 demonstrating extensive, symmetric fasciitis on STIR axial image.

Table 1. Juvenile eosinophilic fasciitis cohort patient characteristics. Bolded laboratory values are elevated above reference ranges.

Table 1. Juvenile eosinophilic fasciitis cohort patient characteristics. Bolded laboratory values are elevated above reference ranges.

Figure 2. Positive prayer sign at initial presentation in juvenile eosinophilic fasciitis. Here are examples of patients 3, 4, 5, and 6 demonstrating a positive prayer sign at the initial diagnosis. The prayer sign is due to skin induration and fascial fibrosis leading to joint contractures and tendon retraction.

Figure 2. Positive prayer sign at initial presentation in juvenile eosinophilic fasciitis. Here are examples of patients 3, 4, 5, and 6 demonstrating a positive prayer sign at the initial diagnosis. The prayer sign is due to skin induration and fascial fibrosis leading to joint contractures and tendon retraction.

Disclosures: L. Stubbs, None; O. Ogunbona, None; A. Adesina, None; S. Anvari, None; E. Beil, None; J. Lai, None; A. Ramirez, None; V. Szafron, None; M. Ditzler, None; M. DeGuzman, None.

Background/Purpose: Eosinophilic fasciitis (EF) is a rare fibrosing disease. Since described in 1975, less than 30 pediatric cases have been reported. EF presents with painful swelling and progressive skin induration causing peau d' orange appearance and the groove sign. Laboratory findings include elevated inflammatory markers, aldolase, eosinophils, and immunoglobulin G. EF diagnosis requires biopsy or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) indicating fasciitis. Risk factors for treatment resistance include concurrent morphea and pediatric age of onset. As triggers, presentation, treatment, and course often differ between pediatric and adult patients, it is important to further characterize juvenile EF cohorts.

Methods: We report the demographics, clinical findings, pathology, MRIs, treatment, and outcomes for six patients with juvenile EF. A retrospective chart review was performed for all patients diagnosed with EF at our institution between November 2011- May 2022. Inclusion criteria included age at diagnosis < 18 years as well as EF confirmation by histology and MRI (Figure 1).

Results: For our juvenile EF cohort, the majority were female (83%) (Table 1). There were 50% Hispanic and 50% non-Hispanic patients. Age at diagnosis ranged from 4-16 years (median: 13) with associated follow-up ranging from 2 months to 12 years. Duration of symptoms prior to diagnosis ranged from 1 month to 1 year (median: 9 months). Associated medical conditions included localized scleroderma (50%), Hashimoto's thyroiditis, 22q11 deletion, and acquired hemophilia A. Most patients presented with bilateral, progressive painful swelling and severe joint limitation mostly without any positive skin findings; one patient presented with unilateral involvement. All patients presented with a positive prayer sign (Figure 2). Initial treatment included corticosteroids and methotrexate. Other medications included hydroxychloroquine, immunoglobulin, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab, and tocilizumab. Two patients had relapse of both morphea and fasciitis. Now, 83% are in remission with the remaining patient with resolved musculoskeletal symptoms and an improving factor 8 level after 2 months of treatment.

Conclusion: Juvenile EF can present with swelling and progressive induration without skin abnormalities. Unlike adult cohorts, there were no underlying malignancies or associations with significant trauma. Previous juvenile EF cohorts have described systemic involvement (hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy), which was not present within this cohort. Although non-specific, the prayer sign could be a helpful clinical finding to identify juvenile EF leading to early recognition and preventing long-term disabling outcomes.

Figure 1. Examples of eosinophilic fasciitis pathology and MRI findings. (A) Left lower leg muscle and fascia biopsy from patient 4 consistent with eosinophilic fasciitis. Hematoxylin and eosin (H &E) section (magnification, x100) showing fascia with underlying muscle. The fascia shows thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration (many macrophages and lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and rare eosinophils). (B) MRI bilateral thighs with and without contrast of patient 4 demonstrating extensive, symmetric fasciitis on STIR axial image.

Figure 1. Examples of eosinophilic fasciitis pathology and MRI findings. (A) Left lower leg muscle and fascia biopsy from patient 4 consistent with eosinophilic fasciitis. Hematoxylin and eosin (H &E) section (magnification, x100) showing fascia with underlying muscle. The fascia shows thickening and inflammatory cell infiltration (many macrophages and lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and rare eosinophils). (B) MRI bilateral thighs with and without contrast of patient 4 demonstrating extensive, symmetric fasciitis on STIR axial image.  Table 1. Juvenile eosinophilic fasciitis cohort patient characteristics. Bolded laboratory values are elevated above reference ranges.

Table 1. Juvenile eosinophilic fasciitis cohort patient characteristics. Bolded laboratory values are elevated above reference ranges.  Figure 2. Positive prayer sign at initial presentation in juvenile eosinophilic fasciitis. Here are examples of patients 3, 4, 5, and 6 demonstrating a positive prayer sign at the initial diagnosis. The prayer sign is due to skin induration and fascial fibrosis leading to joint contractures and tendon retraction.

Figure 2. Positive prayer sign at initial presentation in juvenile eosinophilic fasciitis. Here are examples of patients 3, 4, 5, and 6 demonstrating a positive prayer sign at the initial diagnosis. The prayer sign is due to skin induration and fascial fibrosis leading to joint contractures and tendon retraction.Disclosures: L. Stubbs, None; O. Ogunbona, None; A. Adesina, None; S. Anvari, None; E. Beil, None; J. Lai, None; A. Ramirez, None; V. Szafron, None; M. Ditzler, None; M. DeGuzman, None.