Back

Poster Session A

Vasculitis

Session: (0458–0497) Vasculitis – Non-ANCA-Associated and Related Disorders Poster I: Giant Cell Arteritis

0473: Comprehensive Assessment of Cranial and Orbital Vasculature on MRI in Patients with Giant Cell Arteritis

Saturday, November 12, 2022

1:00 PM – 3:00 PM Eastern Time

Location: Virtual Poster Hall

- RR

Rennie Rhee, MD, MS

University of Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, PA, United States

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Rennie Rhee, Shubhasree Banerjee, Vatsal Bhatt, Madhura Tamhankar, Naomi Amudala, Sherry Chou, Morgan Burke, Laurie Loevner, Peter Merkel and Jae Song, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Background/Purpose: Vessel wall MRI depicts changes consistent with arterial wall inflammation. Unlike temporal artery biopsy, MRI visualizes several full-length cranial arteries in a single scan mitigating sampling error. MRI also evaluates orbital arteries posterior to the ocular globe, an area not visualized by ophthalmologic exam. While previous studies demonstrated good diagnostic performance of MRI in evaluating temporal arteries in giant cell arteritis (GCA), little is known about changes to other cranial and orbital arteries. This study compared MRI enhancement of multiple cranial and orbital arteries in patients with GCA versus controls.

Methods: Patients with suspected new or relapsing cranial GCA who underwent vessel wall brain and/or orbital MRI at presentation were included in the study. A clinical diagnosis of active ocular GCA or non-ocular GCA was determined by a rheumatologist and/or ophthalmologist and confirmed retrospectively. All MR images were scored by a single radiologist blinded to clinical data. Semi-quantitative integer scores of MRI enhancement were determined: cranial arteries were each scored 0, 1, 2, or 3 (score 2-3 defined as abnormal) and orbital structures were each scored 0, 1, or 2 (score 1-2 defined as abnormal). Fisher’s exact test was used for group comparisons and Spearman’s rank for correlations between MRI scores and ESR/CRP levels.

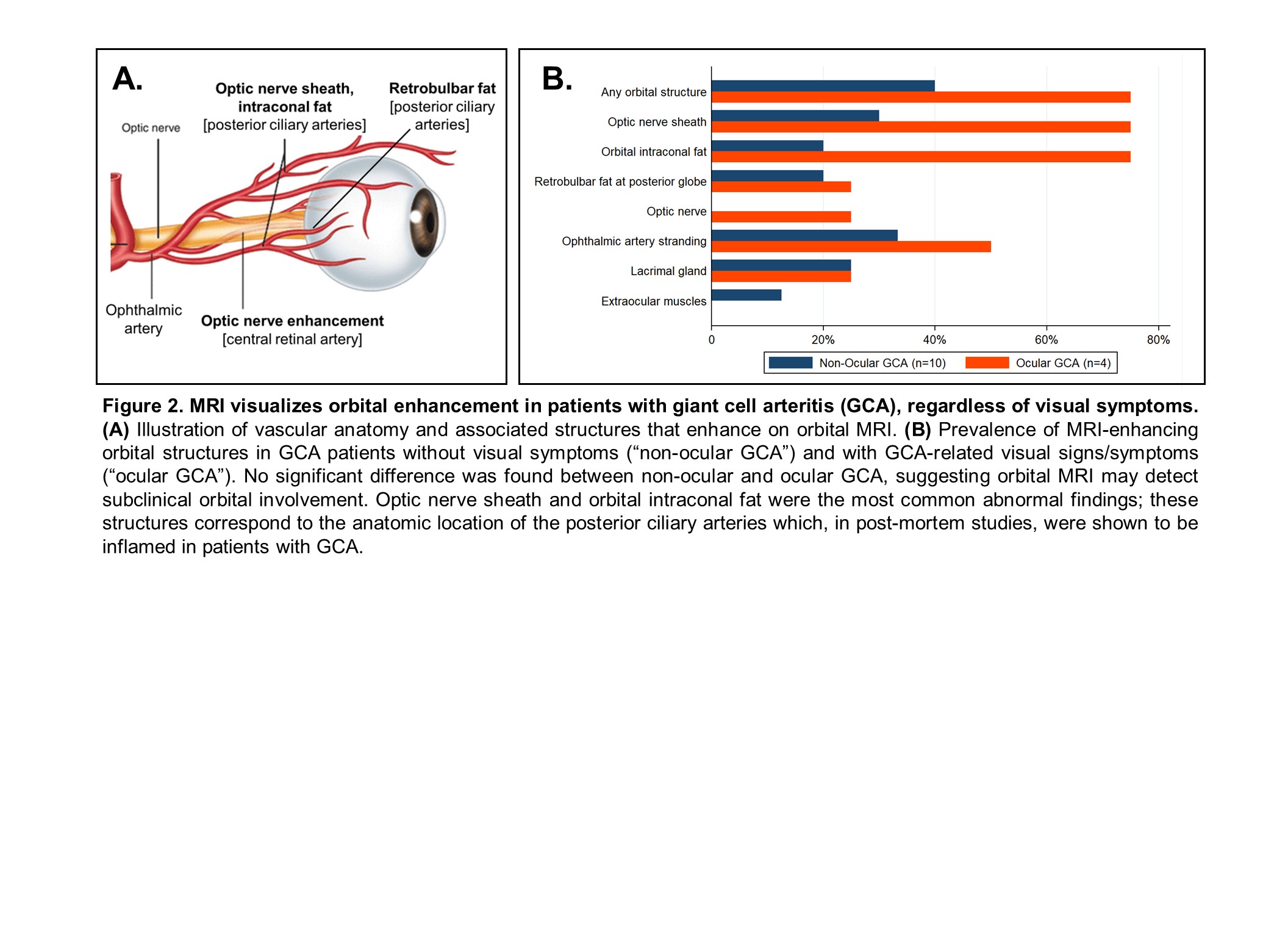

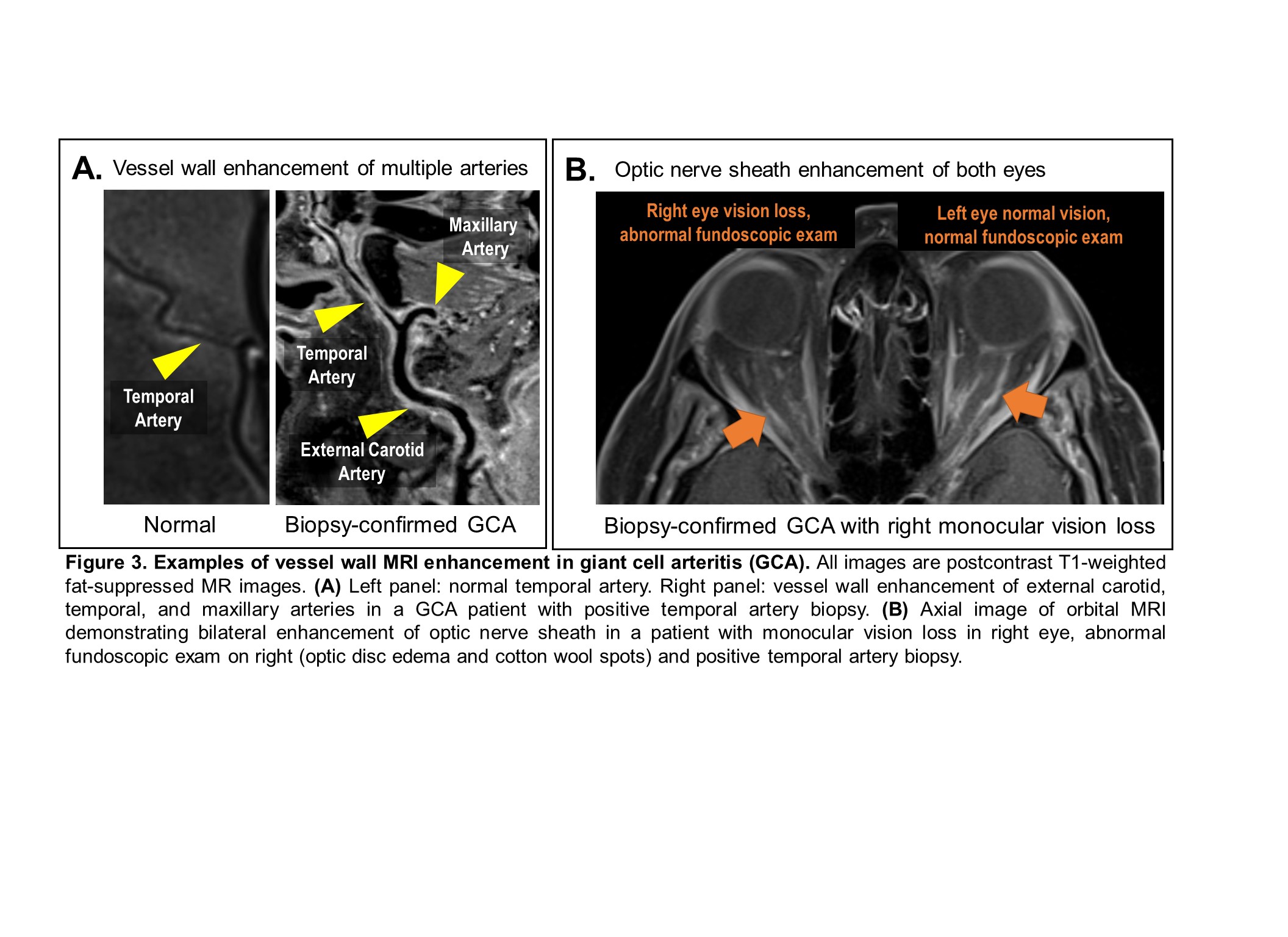

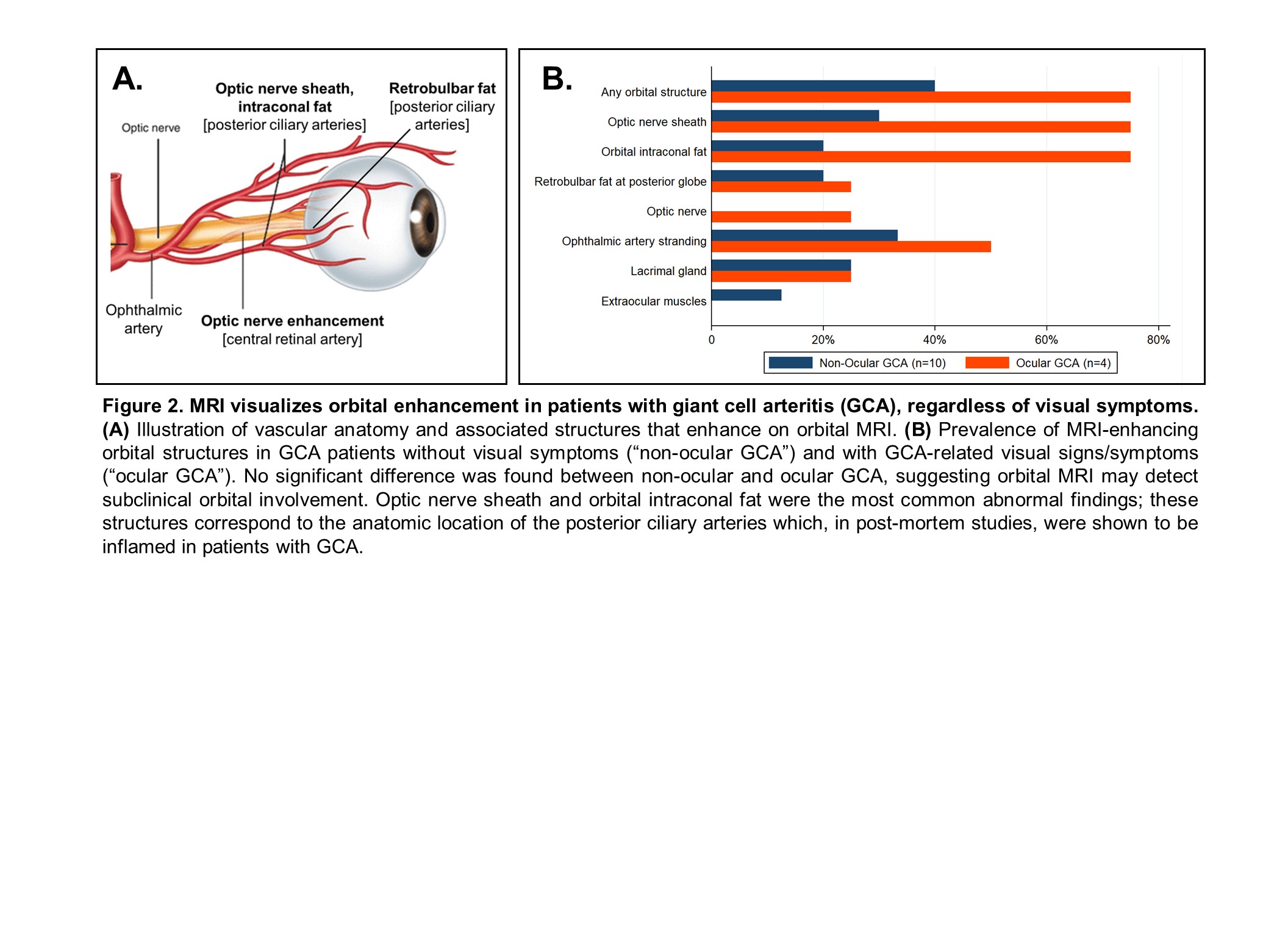

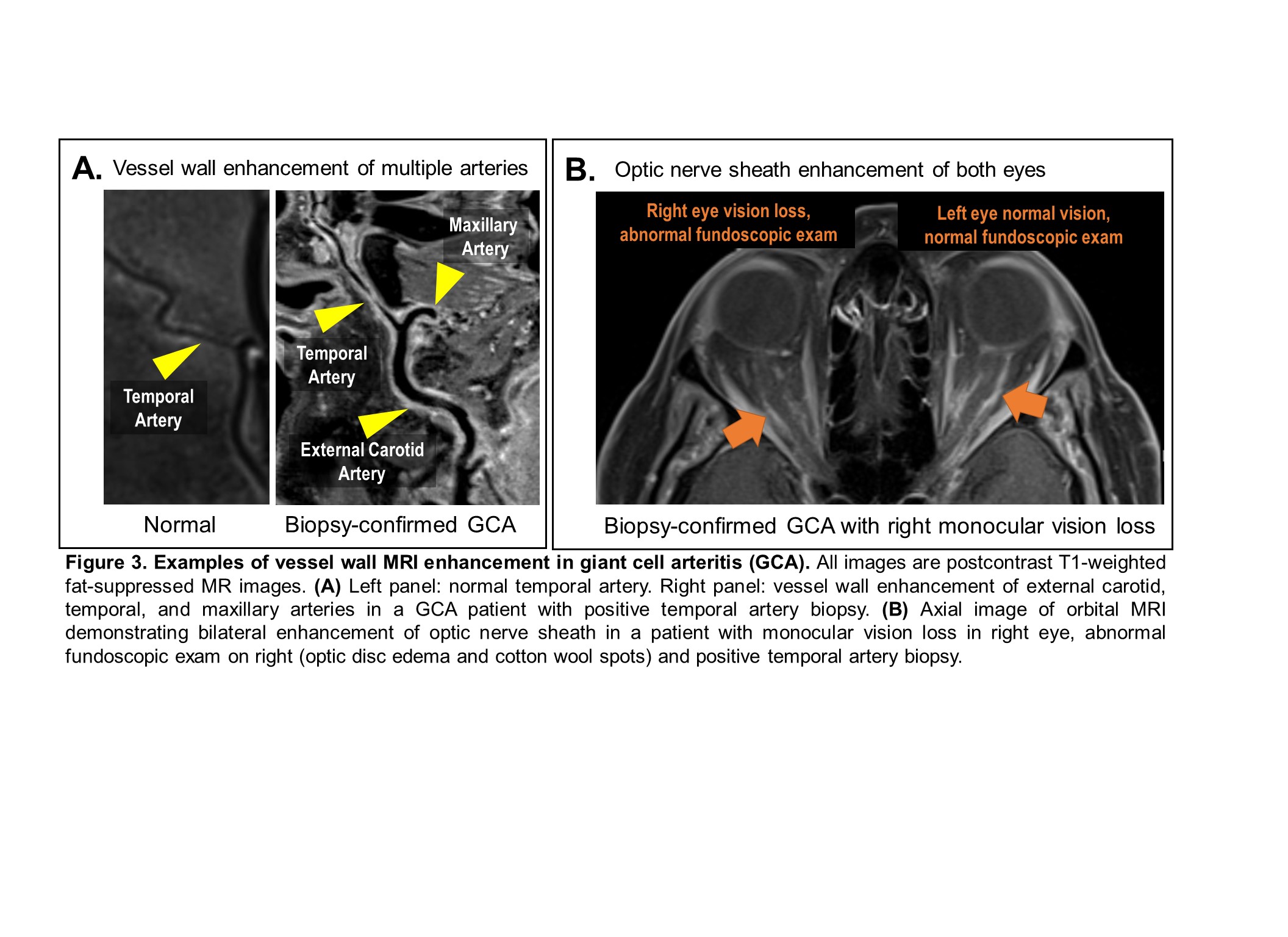

Results: 36 patients had cranial arteries visualized on vessel wall MRI (final clinical diagnosis: 13 with GCA; 23 non-GCA) and 40 patients had orbital structures visualized on MRI (final clinical diagnosis: 4 ocular GCA [confirmed on fundoscopy]; 10 non-ocular GCA; 26 non-GCA). No patient in the non-GCA group had abnormal cranial artery enhancement. Among patients diagnosed with GCA, enhancement was observed in multiple arteries known to be affected by GCA with the most common being the temporal arteries (80%) and occipital arteries (58%)(Figure 1). MRI depicted multiple enhancing orbital structures which corresponded with vascular territories known to contribute to ischemic optic neuropathy in GCA (Figure 2). Orbital enhancement was observed in both ocular and non-ocular GCA (all P > 0.05). Example MR images are shown in Figure 3 including a patient with monocular vision loss who had bilateral orbital enhancement on MRI. Higher CRP levels were associated with higher composite and mean orbital MRI scores (ρ = 0.7, P = 0.02); no associations were found with cranial artery scores and ESR or CRP. In four (11%) of the 36 brain MRIs, a separate clinically important abnormality was found including stroke, malignancy, or aneurysm.

Conclusion: Beyond the temporal arteries, MRI identifies abnormal enhancement of multiple cranial and orbital arteries in patients with GCA all in a single scan. Compared to temporal artery ultrasound and biopsy, cross-sectional MR imaging examines a broader range of arterial territories including the most feared complication of orbital involvement. Future applications of vessel wall MRI in GCA may include risk stratification (e.g., subclinical orbital involvement), disease classification, disease activity assessment, and understanding disease pathophysiology.

.jpg)

Disclosures: R. Rhee, None; S. Banerjee, None; V. Bhatt, None; M. Tamhankar, None; N. Amudala, None; S. Chou, None; M. Burke, None; L. Loevner, Guerbet; P. Merkel, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Boeringher-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, ChemoCentryx, Forbius, Genentech/Roche, Genzyme/Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, InflaRx, Neutrolis, Takeda, CSL Behring, Dynacure, EMDSerono, Immagene, Jannsen, Kiniksa, Magenta, Novartis, Pfizer, Q32, Regeneron, Sparrow, Eicos, Electra, Kyverna, UpToDate; J. Song, None.

Background/Purpose: Vessel wall MRI depicts changes consistent with arterial wall inflammation. Unlike temporal artery biopsy, MRI visualizes several full-length cranial arteries in a single scan mitigating sampling error. MRI also evaluates orbital arteries posterior to the ocular globe, an area not visualized by ophthalmologic exam. While previous studies demonstrated good diagnostic performance of MRI in evaluating temporal arteries in giant cell arteritis (GCA), little is known about changes to other cranial and orbital arteries. This study compared MRI enhancement of multiple cranial and orbital arteries in patients with GCA versus controls.

Methods: Patients with suspected new or relapsing cranial GCA who underwent vessel wall brain and/or orbital MRI at presentation were included in the study. A clinical diagnosis of active ocular GCA or non-ocular GCA was determined by a rheumatologist and/or ophthalmologist and confirmed retrospectively. All MR images were scored by a single radiologist blinded to clinical data. Semi-quantitative integer scores of MRI enhancement were determined: cranial arteries were each scored 0, 1, 2, or 3 (score 2-3 defined as abnormal) and orbital structures were each scored 0, 1, or 2 (score 1-2 defined as abnormal). Fisher’s exact test was used for group comparisons and Spearman’s rank for correlations between MRI scores and ESR/CRP levels.

Results: 36 patients had cranial arteries visualized on vessel wall MRI (final clinical diagnosis: 13 with GCA; 23 non-GCA) and 40 patients had orbital structures visualized on MRI (final clinical diagnosis: 4 ocular GCA [confirmed on fundoscopy]; 10 non-ocular GCA; 26 non-GCA). No patient in the non-GCA group had abnormal cranial artery enhancement. Among patients diagnosed with GCA, enhancement was observed in multiple arteries known to be affected by GCA with the most common being the temporal arteries (80%) and occipital arteries (58%)(Figure 1). MRI depicted multiple enhancing orbital structures which corresponded with vascular territories known to contribute to ischemic optic neuropathy in GCA (Figure 2). Orbital enhancement was observed in both ocular and non-ocular GCA (all P > 0.05). Example MR images are shown in Figure 3 including a patient with monocular vision loss who had bilateral orbital enhancement on MRI. Higher CRP levels were associated with higher composite and mean orbital MRI scores (ρ = 0.7, P = 0.02); no associations were found with cranial artery scores and ESR or CRP. In four (11%) of the 36 brain MRIs, a separate clinically important abnormality was found including stroke, malignancy, or aneurysm.

Conclusion: Beyond the temporal arteries, MRI identifies abnormal enhancement of multiple cranial and orbital arteries in patients with GCA all in a single scan. Compared to temporal artery ultrasound and biopsy, cross-sectional MR imaging examines a broader range of arterial territories including the most feared complication of orbital involvement. Future applications of vessel wall MRI in GCA may include risk stratification (e.g., subclinical orbital involvement), disease classification, disease activity assessment, and understanding disease pathophysiology.

.jpg)

Disclosures: R. Rhee, None; S. Banerjee, None; V. Bhatt, None; M. Tamhankar, None; N. Amudala, None; S. Chou, None; M. Burke, None; L. Loevner, Guerbet; P. Merkel, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Boeringher-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, ChemoCentryx, Forbius, Genentech/Roche, Genzyme/Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, InflaRx, Neutrolis, Takeda, CSL Behring, Dynacure, EMDSerono, Immagene, Jannsen, Kiniksa, Magenta, Novartis, Pfizer, Q32, Regeneron, Sparrow, Eicos, Electra, Kyverna, UpToDate; J. Song, None.