Back

Poster Session B

Reproductive health

Session: (0939–0969) Reproductive Issues in Rheumatic Disorders Poster

0964: High Rates of Fetal Growth Restriction in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Pregnancies

Sunday, November 13, 2022

9:00 AM – 10:30 AM Eastern Time

Location: Virtual Poster Hall

- RW

Raeann Whitney, MD

Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Murfreesboro, TN, United States

Abstract Poster Presenter(s)

Raeann Whitney, Sarah Green, Alex Camai, Ashley Suh, Katherine Walker, Wheless Lee and April Barnado, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN

Background/Purpose: Fetal growth restriction (FGR) and small for gestational age (SGA) are associated with increased perinatal morbidity and mortality. While Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) increases the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, less is known about FGR and SGA in SLE. Using a de-identified electronic health record (EHR), we compared rates of FGR and SGA in women with SLE and women without autoimmune diseases.

Methods: We used a de-identified EHR with over 3.4 million subjects to identify SLE pregnancies with ≥ 4 SLE ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes and ≥ 1 validated pregnancy or delivery related code. We confirmed SLE diagnosis by a rheumatologist and delivery after diagnosis on chart review. Control pregnancies were selected in patients without codes for autoimmune disorders and at least one pregnancy or delivery related code (Figure 1). Of these controls, 250 patients were randomly selected for chart review to confirm no autoimmune diseases. FGR was defined as estimated fetal weight < 10th percentile for gestational age determined by last ultrasound prior to delivery or by documentation of FGR by an obstetrics and gynecology physician. SGA was defined as birth weight < 10th percentile for gestational age at delivery. FGR and SGA percentiles were calculated according to WHO growth charts. For FGR and SGA, pregnancies with missing data or resulting in a loss < 20 weeks were excluded. Risk factors for FGR and SGA were assessed on chart review. We performed logistic regression for FGR and SGA in SLE cases and controls. With patients contributing multiple pregnancies, we used generalized estimating equation (GEE).

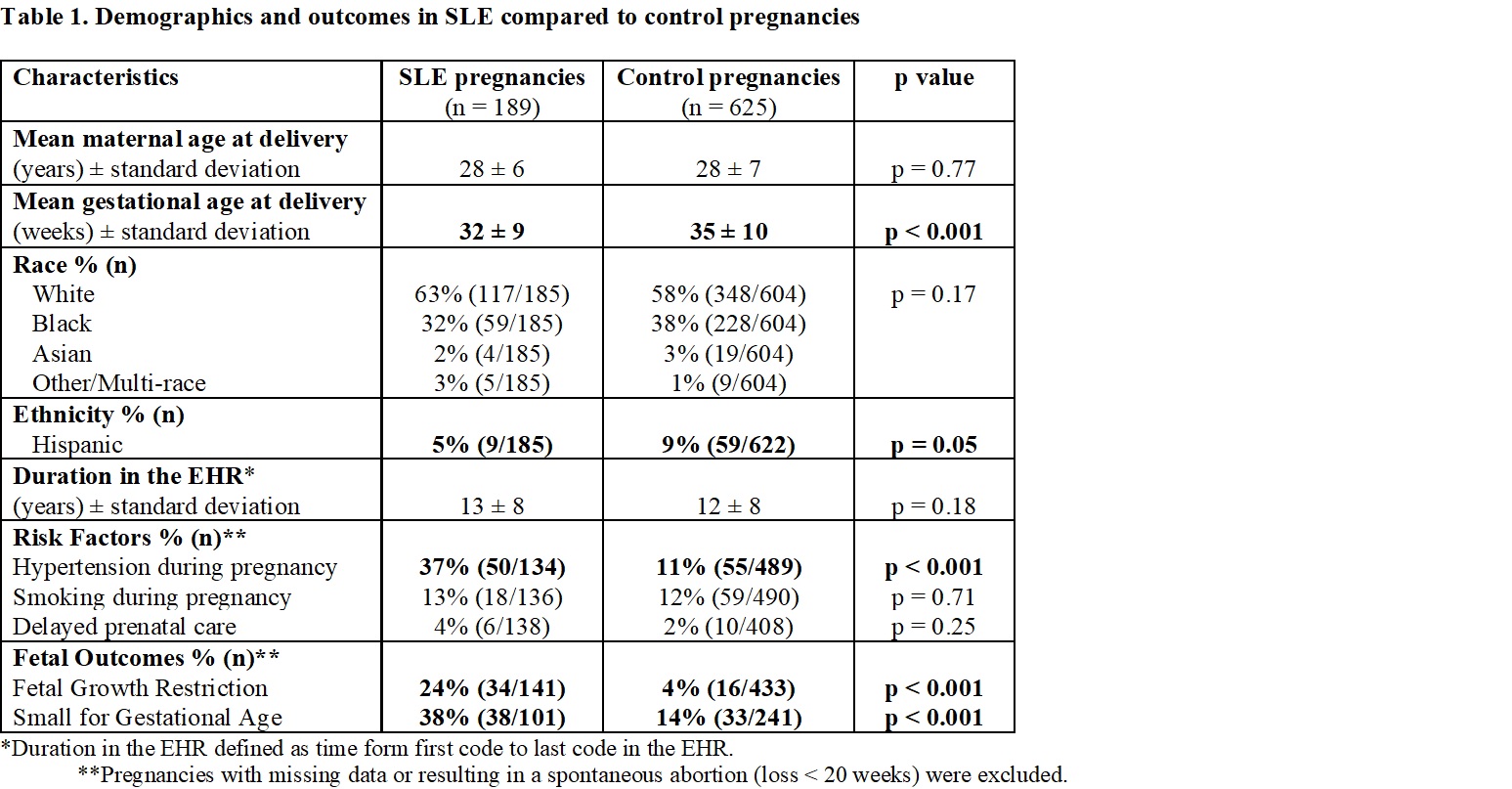

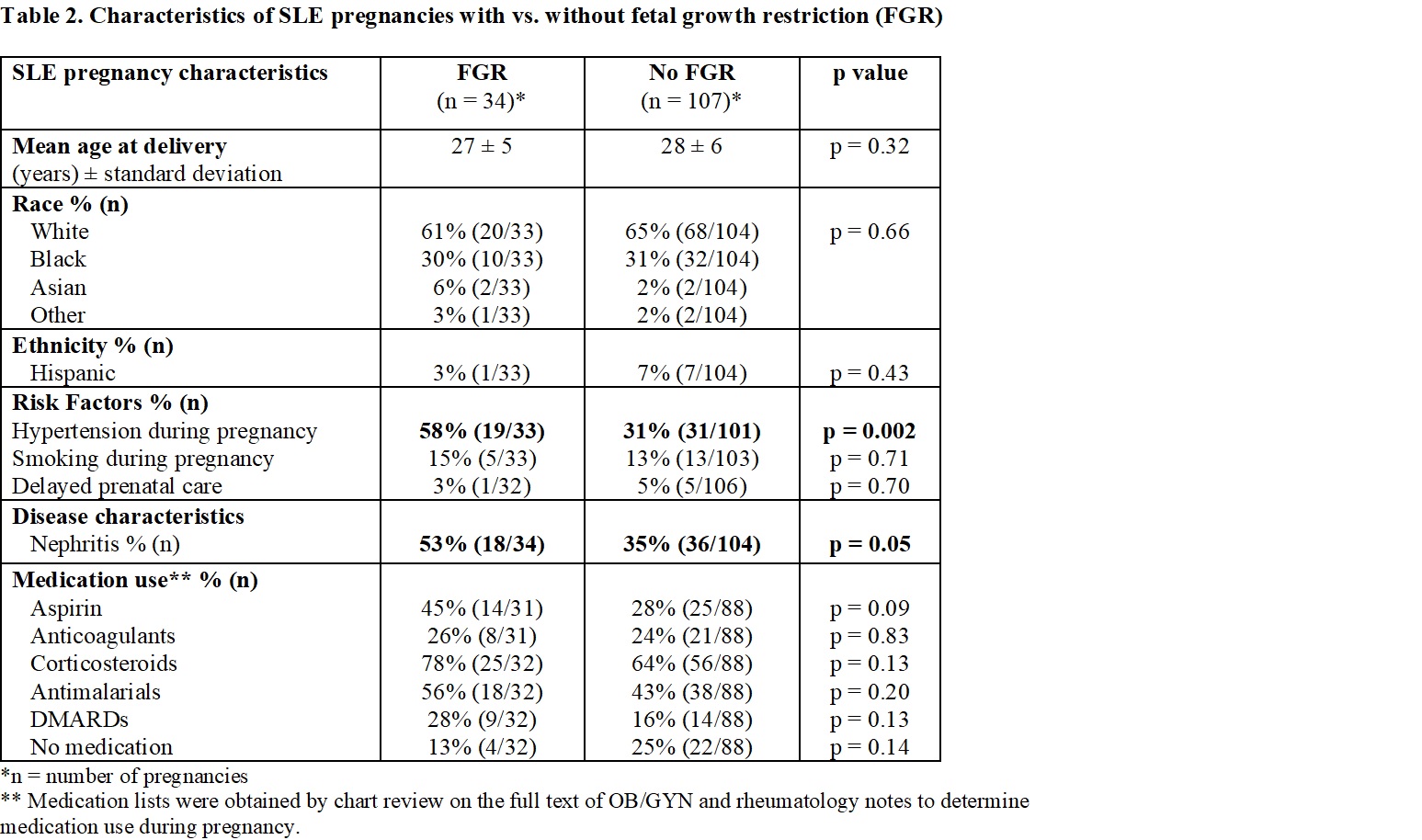

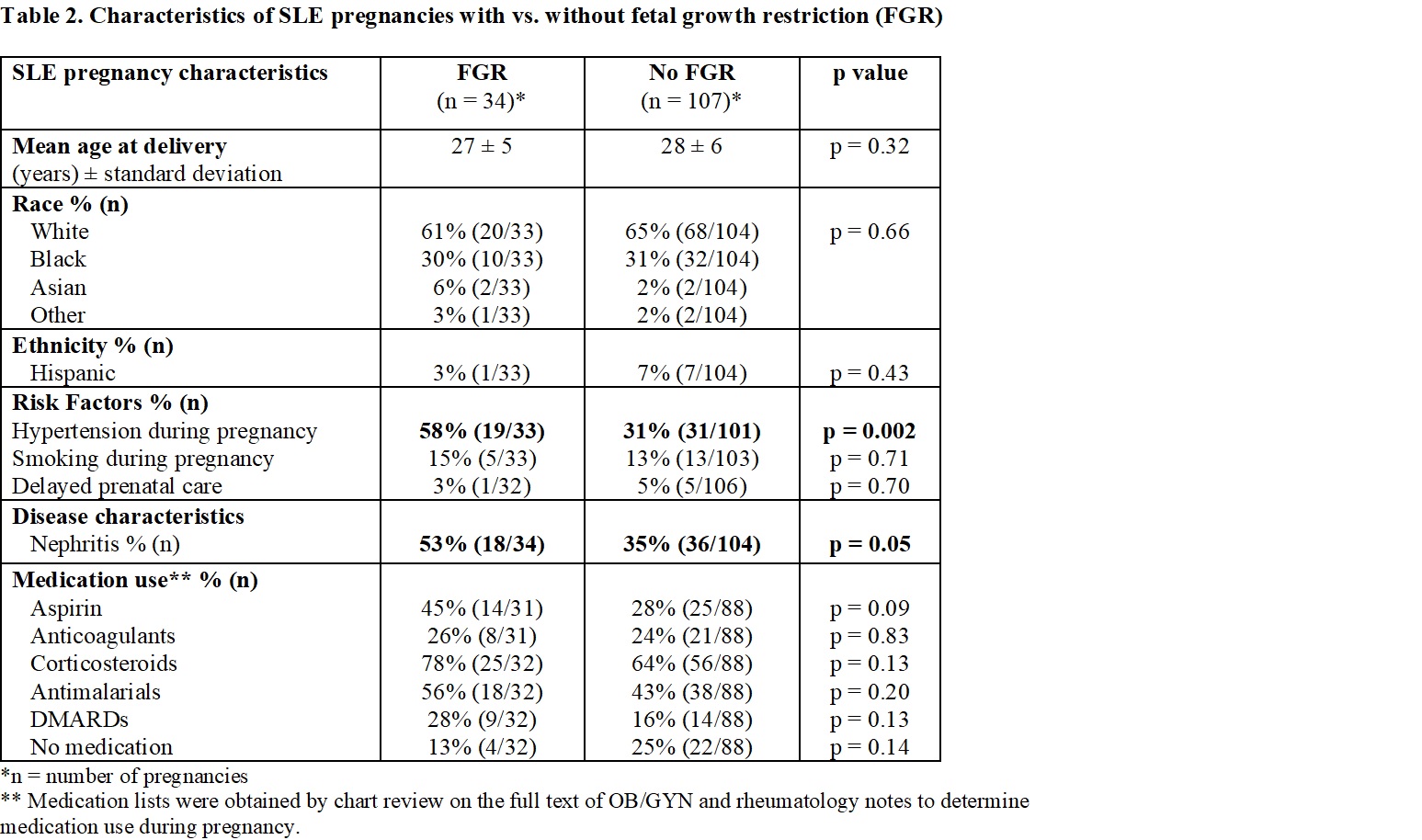

Results: We identified 189 pregnancies to 131 mothers with SLE and 625 pregnancies to 224 control mothers without autoimmune diseases. SLE and control pregnancies were of similar mean age at delivery and of similar race (Table 1). Control pregnancies were more likely to be of Hispanic ethnicity (9% vs. 5%, p = 0.05). Rates of hypertension during pregnancy were higher in SLE vs. control pregnancies (37% vs. 11%, p < 0.001). FGR (24% vs. 4%, p < 0.001) and SGA (38% vs. 14%, p < 0.001) were significantly higher in SLE vs. control pregnancies. SLE case status (OR = 6.38, 95% CI 3.21 – 13.12, p < 0.001) and hypertension (OR = 3.40, 95% CI 1.70 – 6.78, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with FGR after adjusting for age at delivery and race. SLE case status (OR = 3.59, 95% CI 1.96-6.63, p < 0.001) and hypertension (OR = 2.03, 95% CI 1.01 – 4.04, p = 0.05) were also significantly associated with SGA after adjusting for age at delivery and race. Estimates from the GEE were similar. We compared SLE pregnancies with vs. without FGR (Table 2). SLE pregnancies with FGR were more likely to be complicated by nephritis and hypertension with no significant differences in demographics or medication use during pregnancy.

Conclusion: Patients with SLE are at a significantly higher risk for FGR and SGA compared to patients without autoimmune diseases even after adjusting for demographics and risk factors. FGR occurred more frequently in SLE patients whose pregnancies were complicated by nephritis and hypertension. Hypertension is a modifiable risk that should be aggressively managed in SLE pregnancies to reduce risk of FGR and SGA.

.jpg)

Disclosures: R. Whitney, None; S. Green, None; A. Camai, None; A. Suh, None; K. Walker, None; W. Lee, None; A. Barnado, None.

Background/Purpose: Fetal growth restriction (FGR) and small for gestational age (SGA) are associated with increased perinatal morbidity and mortality. While Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) increases the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes, less is known about FGR and SGA in SLE. Using a de-identified electronic health record (EHR), we compared rates of FGR and SGA in women with SLE and women without autoimmune diseases.

Methods: We used a de-identified EHR with over 3.4 million subjects to identify SLE pregnancies with ≥ 4 SLE ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes and ≥ 1 validated pregnancy or delivery related code. We confirmed SLE diagnosis by a rheumatologist and delivery after diagnosis on chart review. Control pregnancies were selected in patients without codes for autoimmune disorders and at least one pregnancy or delivery related code (Figure 1). Of these controls, 250 patients were randomly selected for chart review to confirm no autoimmune diseases. FGR was defined as estimated fetal weight < 10th percentile for gestational age determined by last ultrasound prior to delivery or by documentation of FGR by an obstetrics and gynecology physician. SGA was defined as birth weight < 10th percentile for gestational age at delivery. FGR and SGA percentiles were calculated according to WHO growth charts. For FGR and SGA, pregnancies with missing data or resulting in a loss < 20 weeks were excluded. Risk factors for FGR and SGA were assessed on chart review. We performed logistic regression for FGR and SGA in SLE cases and controls. With patients contributing multiple pregnancies, we used generalized estimating equation (GEE).

Results: We identified 189 pregnancies to 131 mothers with SLE and 625 pregnancies to 224 control mothers without autoimmune diseases. SLE and control pregnancies were of similar mean age at delivery and of similar race (Table 1). Control pregnancies were more likely to be of Hispanic ethnicity (9% vs. 5%, p = 0.05). Rates of hypertension during pregnancy were higher in SLE vs. control pregnancies (37% vs. 11%, p < 0.001). FGR (24% vs. 4%, p < 0.001) and SGA (38% vs. 14%, p < 0.001) were significantly higher in SLE vs. control pregnancies. SLE case status (OR = 6.38, 95% CI 3.21 – 13.12, p < 0.001) and hypertension (OR = 3.40, 95% CI 1.70 – 6.78, p < 0.001) were significantly associated with FGR after adjusting for age at delivery and race. SLE case status (OR = 3.59, 95% CI 1.96-6.63, p < 0.001) and hypertension (OR = 2.03, 95% CI 1.01 – 4.04, p = 0.05) were also significantly associated with SGA after adjusting for age at delivery and race. Estimates from the GEE were similar. We compared SLE pregnancies with vs. without FGR (Table 2). SLE pregnancies with FGR were more likely to be complicated by nephritis and hypertension with no significant differences in demographics or medication use during pregnancy.

Conclusion: Patients with SLE are at a significantly higher risk for FGR and SGA compared to patients without autoimmune diseases even after adjusting for demographics and risk factors. FGR occurred more frequently in SLE patients whose pregnancies were complicated by nephritis and hypertension. Hypertension is a modifiable risk that should be aggressively managed in SLE pregnancies to reduce risk of FGR and SGA.

.jpg)

Disclosures: R. Whitney, None; S. Green, None; A. Camai, None; A. Suh, None; K. Walker, None; W. Lee, None; A. Barnado, None.