Back

Abstract Session

Crystal arthropathies

Session: Abstracts: Metabolic and Crystal Arthropathies – Basic and Clinical Science (1579–1584)

1580: Poor Serum Urate Control Is a Driver of Excess Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Gout

Sunday, November 13, 2022

3:15 PM – 3:25 PM Eastern Time

Location: Room 114 Nutter Theatre

.png)

Tate Johnson, MD

University of Nebraska Medical Center

Omaha, NE, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Tate Johnson1, Lindsay Helget2, Harlan Sayles2, Punyasha Roul3, James O'Dell2, Ted Mikuls4 and Bryant England2, 1University of Nebraska Medical Center, Elkhorn, NE, 2University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, 3UNMC, Omaha, NE, 4Division of Rheumatology, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE

Background/Purpose: Gout patients suffer from an increased burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD). It remains unclear whether this risk is related to an excess of CVD risk factors, unique pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying gout, and/or inadequate gout management. Furthermore, while atherothrombotic CVD event risk has been extensively studied, there is a relative paucity of information on risk of incident heart failure (HF) in gout. Thus, we evaluated the associations of gout and gout treatment status with major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), HF hospitalization, and CVD-related death in a national cohort of US Veterans.

Methods: We performed a retrospective, matched cohort study in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) from 1/1999 to 9/2015. Patients with gout (≥2 ICD-9 codes) were matched up to 1:10 on age, sex, and year of VHA enrollment to patients without a gout ICD-9 code or urate lowering therapy (ULT) dispensing. CVD events (overall, fatal and non-fatal MACE, HF hospitalization, HF death) were identified using validated diagnostic and procedure codes in VHA and linked National Death Index data. Among gout patients, gout treatment status was defined in a time-varying manner over 12-month intervals (including a lag to prevent reverse causation) based on adequate serum urate (SU) control (< 6 mg/dL) and ≥2 dispensings of ULT (Mikuls, JAMA Netw Open, 2022). Multivariable Cox regression models adjusting for CVD risk factors were used to examine the associations of gout and gout treatment status with CVD events.

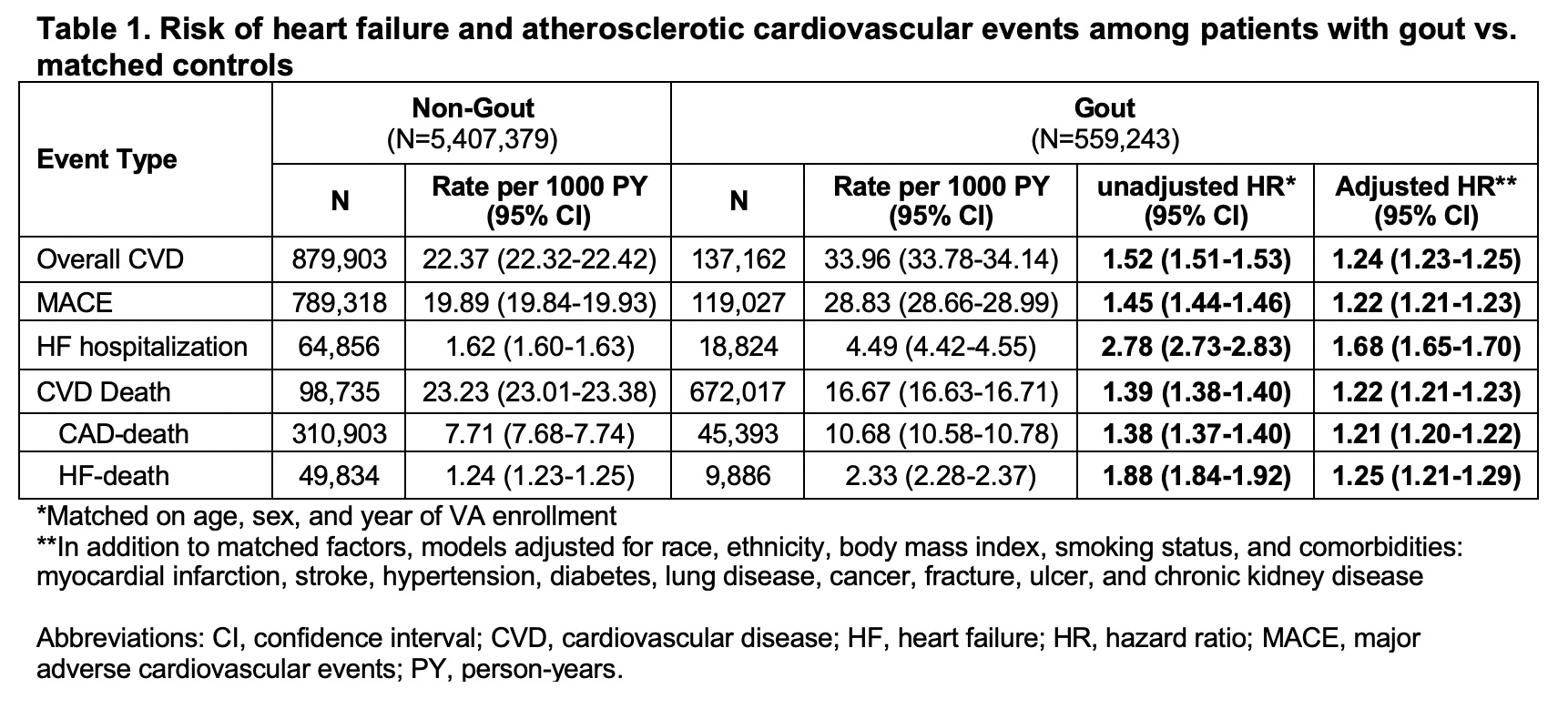

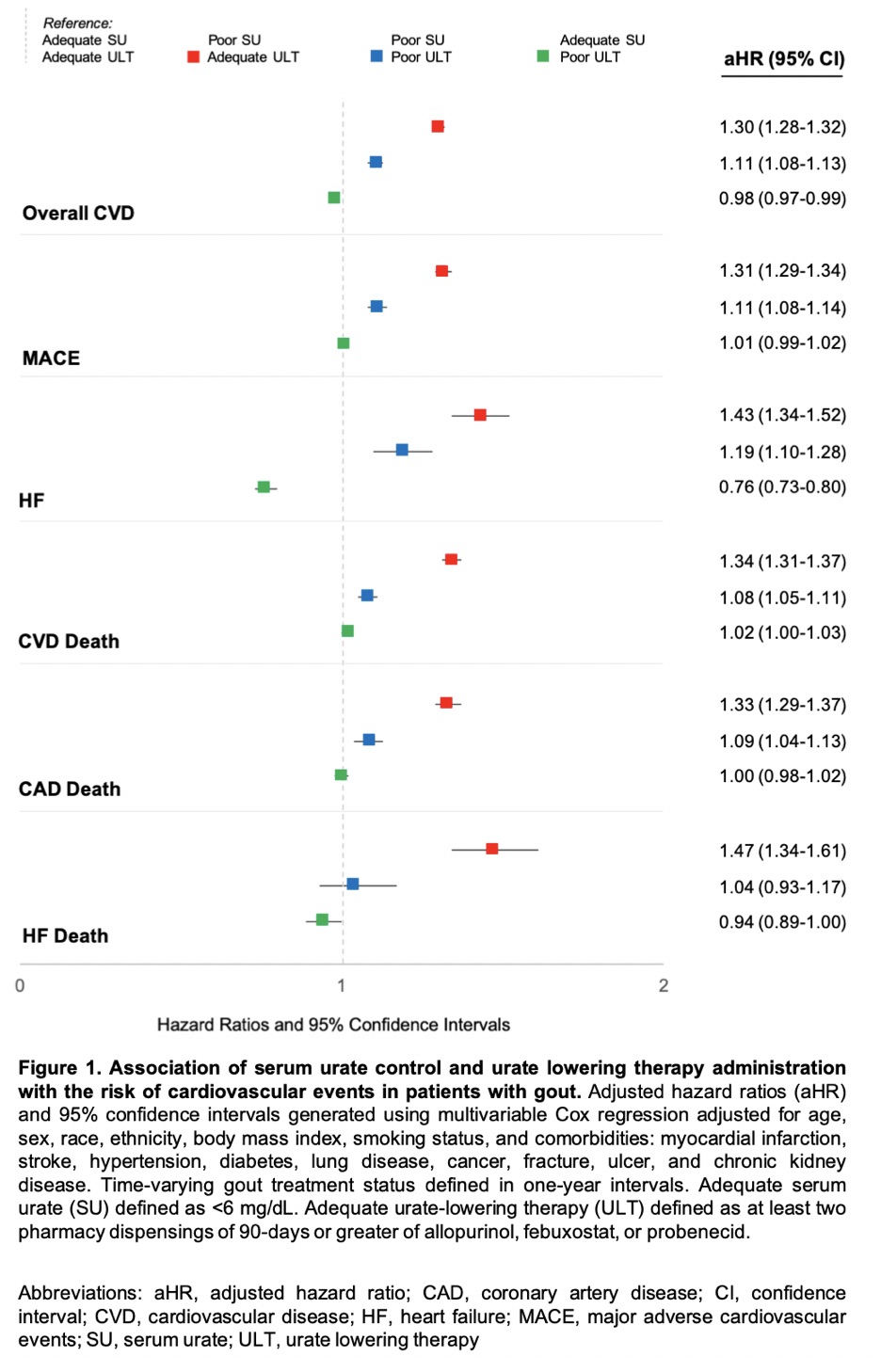

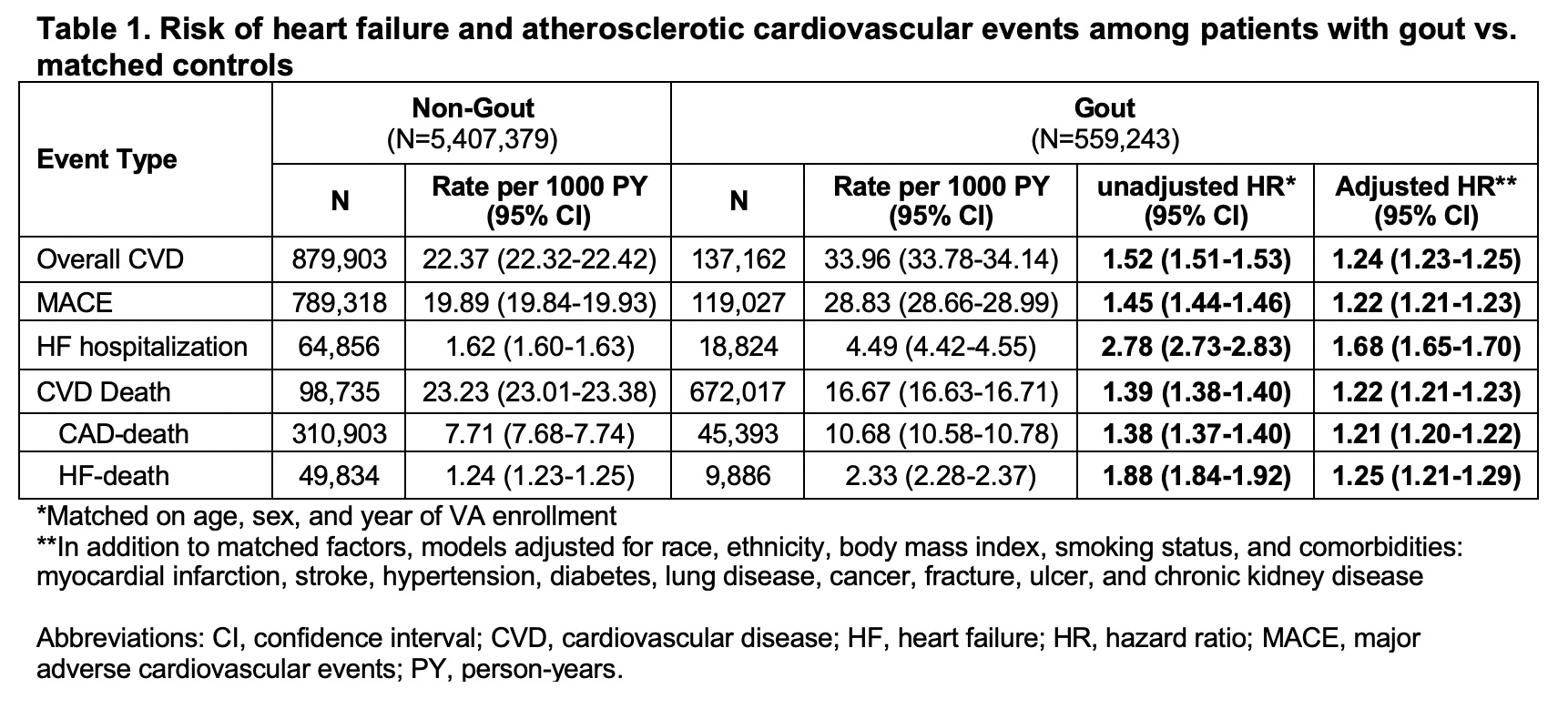

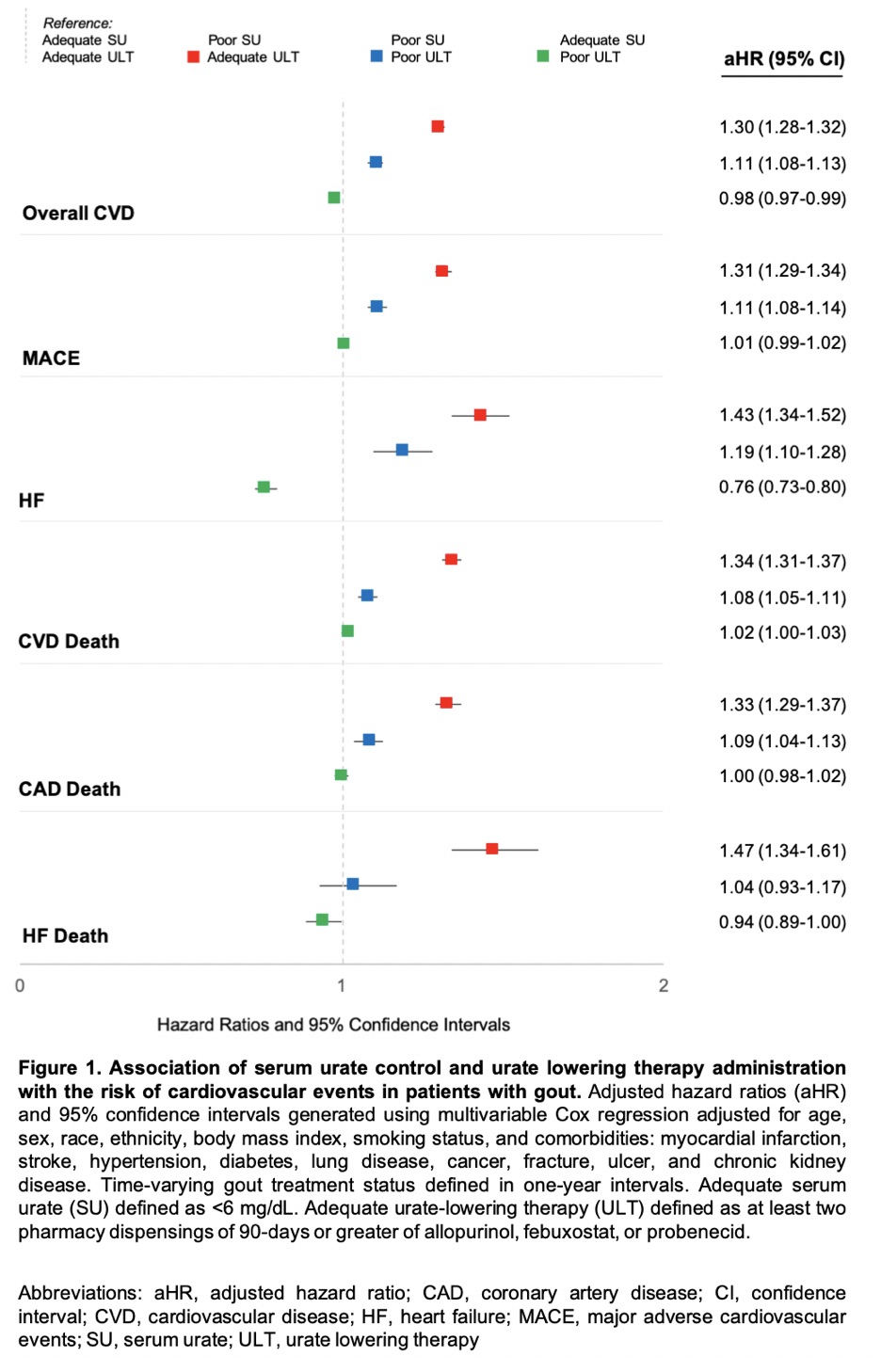

Results: We matched 559,243 gout patients to 5,407,379 non-gout controls (99% male, mean age 67 years). Over 43,331,604 person-years, we observed 137,162 CVD events in gout (IR 33.96 per 1000 PY) vs. 879,903 in non-gout patients (IR 22.37 per 1000 PY). Crude incidence rates of individual CVD events were also higher in gout vs. non-gout (Table 1). Gout was most strongly associated with HF hospitalization, with a nearly 3-fold higher risk (HR 2.78 [2.73-2.83]) that was attenuated but persisted after adjusting for additional CVD risk factors (aHR 1.68 [1.65-1.70]) and excluding patients with prevalent HF (aHR 1.60 [1.57-1.64]). Gout patients were also at higher risk of HF-related death (aHR 1.25 [1.21-1.29]), MACE (aHR 1.22 [1.21-1.23]), and coronary artery disease-related death (aHR 1.21 [1.20-1.22]). Among gout patients, poor SU control was associated with a higher risk of all CVD events, with the highest CVD risk occurring despite receipt of ULT and related to HF hospitalization (aHR 1.43 [1.34-1.52]) and HF-related death (aHR 1.47 [1.34-1.61]) (Figure 1). A 24% lower risk of HF hospitalization was seen in those with controlled SU and poor ULT administration.

Conclusion: In this large, matched cohort study, despite accounting for CVD risk factors, gout was associated with a 68% increased risk of HF hospitalization, 25% increased risk of HF-related death, and a 22% increased risk of MACE. Among gout patients, poorly controlled SU conferred a higher risk of CVD events independent of ULT use, which may represent a surrogate of more severe disease. Continued research investigating a causal link between gout, hyperuricemia, or its treatment, and CVD risk is needed.

Table 1. Risk of heart failure and atherosclerotic cardiovascular events among patients with gout vs. matched controls

Table 1. Risk of heart failure and atherosclerotic cardiovascular events among patients with gout vs. matched controls

Figure 1. Association of serum urate control and urate lowering therapy administration with the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with gout.

Figure 1. Association of serum urate control and urate lowering therapy administration with the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with gout.

Disclosures: T. Johnson, None; L. Helget, None; H. Sayles, None; P. Roul, None; J. O'Dell, None; T. Mikuls, Gilead Sciences, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Horizon, Sanofi, Pfizer Inc; B. England, Boehringer-Ingelheim.

Background/Purpose: Gout patients suffer from an increased burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD). It remains unclear whether this risk is related to an excess of CVD risk factors, unique pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying gout, and/or inadequate gout management. Furthermore, while atherothrombotic CVD event risk has been extensively studied, there is a relative paucity of information on risk of incident heart failure (HF) in gout. Thus, we evaluated the associations of gout and gout treatment status with major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), HF hospitalization, and CVD-related death in a national cohort of US Veterans.

Methods: We performed a retrospective, matched cohort study in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) from 1/1999 to 9/2015. Patients with gout (≥2 ICD-9 codes) were matched up to 1:10 on age, sex, and year of VHA enrollment to patients without a gout ICD-9 code or urate lowering therapy (ULT) dispensing. CVD events (overall, fatal and non-fatal MACE, HF hospitalization, HF death) were identified using validated diagnostic and procedure codes in VHA and linked National Death Index data. Among gout patients, gout treatment status was defined in a time-varying manner over 12-month intervals (including a lag to prevent reverse causation) based on adequate serum urate (SU) control (< 6 mg/dL) and ≥2 dispensings of ULT (Mikuls, JAMA Netw Open, 2022). Multivariable Cox regression models adjusting for CVD risk factors were used to examine the associations of gout and gout treatment status with CVD events.

Results: We matched 559,243 gout patients to 5,407,379 non-gout controls (99% male, mean age 67 years). Over 43,331,604 person-years, we observed 137,162 CVD events in gout (IR 33.96 per 1000 PY) vs. 879,903 in non-gout patients (IR 22.37 per 1000 PY). Crude incidence rates of individual CVD events were also higher in gout vs. non-gout (Table 1). Gout was most strongly associated with HF hospitalization, with a nearly 3-fold higher risk (HR 2.78 [2.73-2.83]) that was attenuated but persisted after adjusting for additional CVD risk factors (aHR 1.68 [1.65-1.70]) and excluding patients with prevalent HF (aHR 1.60 [1.57-1.64]). Gout patients were also at higher risk of HF-related death (aHR 1.25 [1.21-1.29]), MACE (aHR 1.22 [1.21-1.23]), and coronary artery disease-related death (aHR 1.21 [1.20-1.22]). Among gout patients, poor SU control was associated with a higher risk of all CVD events, with the highest CVD risk occurring despite receipt of ULT and related to HF hospitalization (aHR 1.43 [1.34-1.52]) and HF-related death (aHR 1.47 [1.34-1.61]) (Figure 1). A 24% lower risk of HF hospitalization was seen in those with controlled SU and poor ULT administration.

Conclusion: In this large, matched cohort study, despite accounting for CVD risk factors, gout was associated with a 68% increased risk of HF hospitalization, 25% increased risk of HF-related death, and a 22% increased risk of MACE. Among gout patients, poorly controlled SU conferred a higher risk of CVD events independent of ULT use, which may represent a surrogate of more severe disease. Continued research investigating a causal link between gout, hyperuricemia, or its treatment, and CVD risk is needed.

Table 1. Risk of heart failure and atherosclerotic cardiovascular events among patients with gout vs. matched controls

Table 1. Risk of heart failure and atherosclerotic cardiovascular events among patients with gout vs. matched controls Figure 1. Association of serum urate control and urate lowering therapy administration with the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with gout.

Figure 1. Association of serum urate control and urate lowering therapy administration with the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with gout. Disclosures: T. Johnson, None; L. Helget, None; H. Sayles, None; P. Roul, None; J. O'Dell, None; T. Mikuls, Gilead Sciences, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Horizon, Sanofi, Pfizer Inc; B. England, Boehringer-Ingelheim.