Back

Poster Session A - Sunday Afternoon

Category: Esophagus

A0234 - When All You See Is Black: A Case of Acute Esophageal Necrosis

Sunday, October 23, 2022

5:00 PM – 7:00 PM ET

Location: Crown Ballroom

Has Audio

John Green, DO, MPH

University of South Alabama College of Medicine

Daphne, AL

Presenting Author(s)

J. Alvin Green, DO, MPH1, Rebecca Browning, DO2, William P. Sonnier, MD2

1University of South Alabama College of Medicine, Daphne, AL; 2University of South Alabama College of Medicine, Mobile, AL

Introduction: Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN), sometimes called “black esophagus” given its endoscopic appearance, is a rare condition with an incidence of around 0.01% of all patients undergoing EGD. The pathophysiology of AEN is hypothesized to be multifactorial involving hemodynamic compromise, backflow of stomach acid, any state where esophageal mucosal repair mechanisms are diminished, or thromboembolic phenomena. The primary associated symptoms are hematemesis, melena, and shock. AEN is a life threatening condition with a mortality rate of approximately 32%.

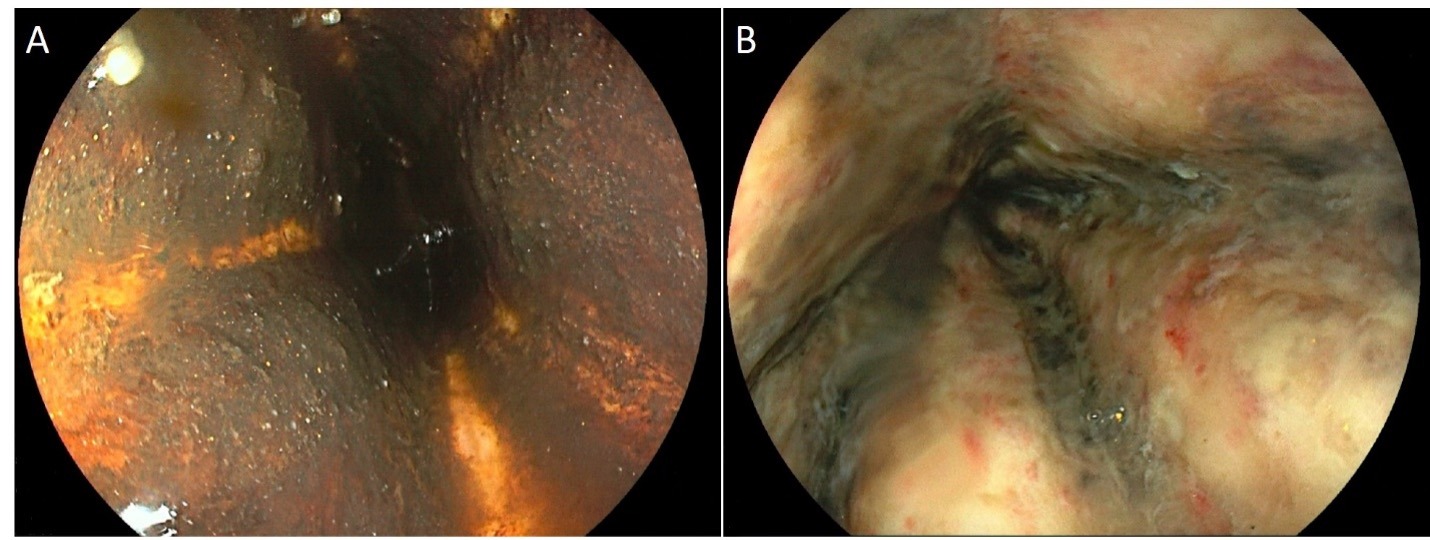

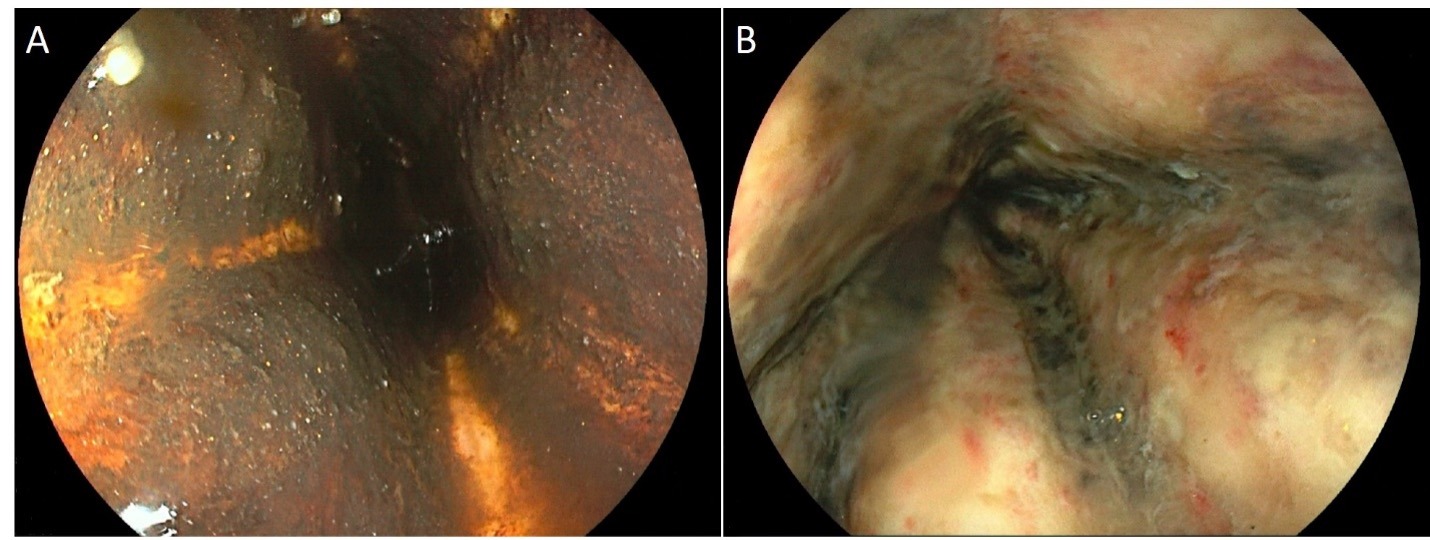

Case Description/Methods: A 73 year old male with a medical history of NASH cirrhosis, hypertension, coronary artery disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and diabetes mellitus type 2 presented from home with hematemesis. He was discharged 24 hours before presentation after spending 5 days in the hospital for hepatic encephalopathy. On physical examination he was afebrile, normotensive with a slight tachycardia. Hemoglobin and hematocrit were 11g/dL and 31%, respectively. He was started on an octreotide drip, given IV Protonix 80 mg, and 1 gram of Ceftriaxone. EGD later that day revealed black material coating the esophagus unable to be washed away, portal hypertensive gastropathy, a large amount of altered blood mixed with food in the stomach, duodenitis, and superficial duodenal ulcers. A repeat EGD 24 hours later revealed ulceration of the mid and distal esophagus consistent with acute esophageal necrosis. A CTA aorta was negative for stenosis or thromboembolic phenomena. He remained hemodynamically stable, did not develop esophageal pain, and was started on a Sucralfate slurry. He was able to progress his diet quickly. Six days after admission his labs normalized and was discharged home.

Discussion: Our patient had multiple factors likely leading to the development of AEN due to his numerous comorbidities. It is important to monitor for complications of AEN, including perforation and microbial superinfection during the initial recovery period, and stenosis or strictures as a late sequala. Due to the patient’s prompt triage and intervention with appropriate therapy, a good outcome was achieved. This case highlights the importance of quickly triaging patients and intervening appropriately to combat the high mortality rate of AEN.

Disclosures:

J. Alvin Green, DO, MPH1, Rebecca Browning, DO2, William P. Sonnier, MD2. A0234 - When All You See Is Black: A Case of Acute Esophageal Necrosis, ACG 2022 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Charlotte, NC: American College of Gastroenterology.

1University of South Alabama College of Medicine, Daphne, AL; 2University of South Alabama College of Medicine, Mobile, AL

Introduction: Acute esophageal necrosis (AEN), sometimes called “black esophagus” given its endoscopic appearance, is a rare condition with an incidence of around 0.01% of all patients undergoing EGD. The pathophysiology of AEN is hypothesized to be multifactorial involving hemodynamic compromise, backflow of stomach acid, any state where esophageal mucosal repair mechanisms are diminished, or thromboembolic phenomena. The primary associated symptoms are hematemesis, melena, and shock. AEN is a life threatening condition with a mortality rate of approximately 32%.

Case Description/Methods: A 73 year old male with a medical history of NASH cirrhosis, hypertension, coronary artery disease, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and diabetes mellitus type 2 presented from home with hematemesis. He was discharged 24 hours before presentation after spending 5 days in the hospital for hepatic encephalopathy. On physical examination he was afebrile, normotensive with a slight tachycardia. Hemoglobin and hematocrit were 11g/dL and 31%, respectively. He was started on an octreotide drip, given IV Protonix 80 mg, and 1 gram of Ceftriaxone. EGD later that day revealed black material coating the esophagus unable to be washed away, portal hypertensive gastropathy, a large amount of altered blood mixed with food in the stomach, duodenitis, and superficial duodenal ulcers. A repeat EGD 24 hours later revealed ulceration of the mid and distal esophagus consistent with acute esophageal necrosis. A CTA aorta was negative for stenosis or thromboembolic phenomena. He remained hemodynamically stable, did not develop esophageal pain, and was started on a Sucralfate slurry. He was able to progress his diet quickly. Six days after admission his labs normalized and was discharged home.

Discussion: Our patient had multiple factors likely leading to the development of AEN due to his numerous comorbidities. It is important to monitor for complications of AEN, including perforation and microbial superinfection during the initial recovery period, and stenosis or strictures as a late sequala. Due to the patient’s prompt triage and intervention with appropriate therapy, a good outcome was achieved. This case highlights the importance of quickly triaging patients and intervening appropriately to combat the high mortality rate of AEN.

Figure: Figure 1: Endoscopic appearance of the esophagus on day of presentation (A) showing black necrotic appearance of esophagus and 24 hours later on repeat examination (B) demonstrating ulcerated esophageal mucosa.

Disclosures:

J. Alvin Green indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Rebecca Browning indicated no relevant financial relationships.

William Sonnier: Abbvie – Speakers Bureau.

J. Alvin Green, DO, MPH1, Rebecca Browning, DO2, William P. Sonnier, MD2. A0234 - When All You See Is Black: A Case of Acute Esophageal Necrosis, ACG 2022 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Charlotte, NC: American College of Gastroenterology.