Back

Poster Session A - Sunday Afternoon

Category: Biliary/Pancreas

A0069 - Hemosuccus Pancreaticus: More Than at First Blush

Sunday, October 23, 2022

5:00 PM – 7:00 PM ET

Location: Crown Ballroom

Has Audio

Hannah W. Fiske, MD

Brown University/Rhode Island Hospital

Providence, RI

Presenting Author(s)

Hannah W. Fiske, MD1, Averill Guo, MD2, Sarah M. Hyder, MD, MBA3

1Brown University/Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI; 2The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI; 3Lifespan Physician Group - Brown University, East Providence, RI

Introduction: Hemosuccus pancreaticus describes hemorrhage from the ampulla of Vater via the pancreatic duct, and is an infrequent but potentially life-threatening cause of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Diagnosis can be elusive and treatment challenging. Here we report a case of hemosuccus pancreaticus in the setting of acute pancreatitis identified on upper endoscopy (EGD) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), treated successfully with gastroduodenal artery (GDA) embolization by interventional radiology.

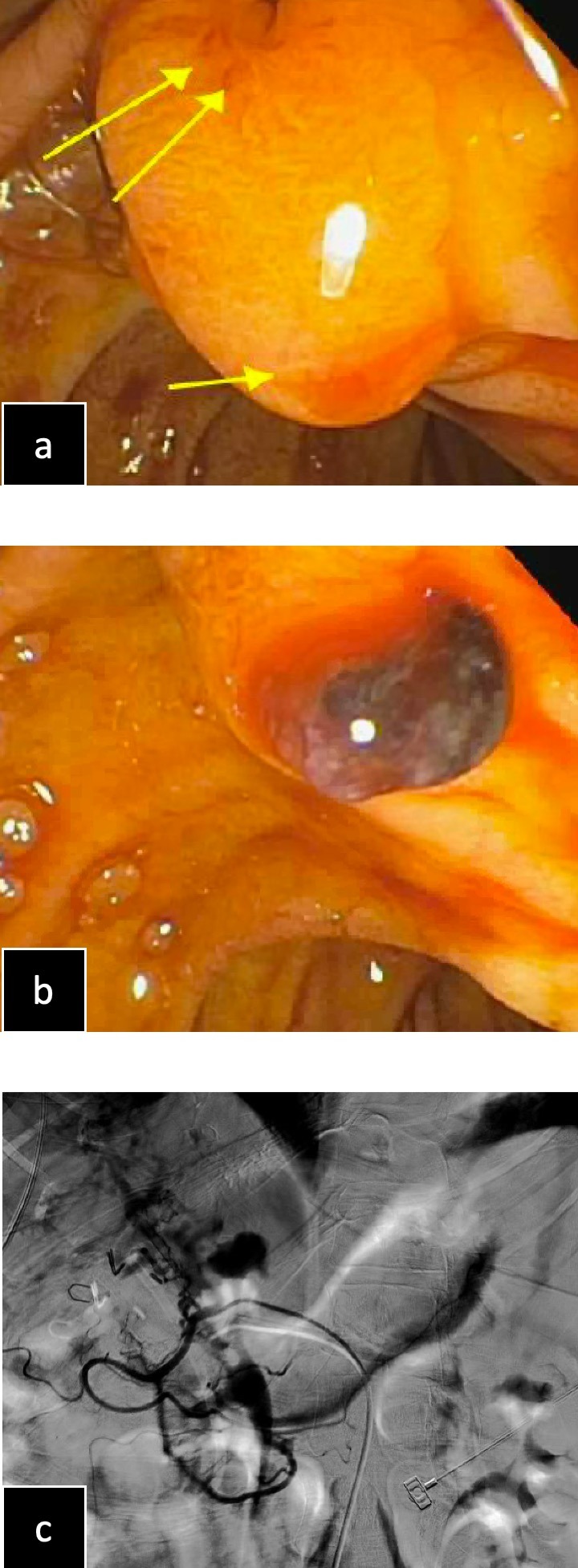

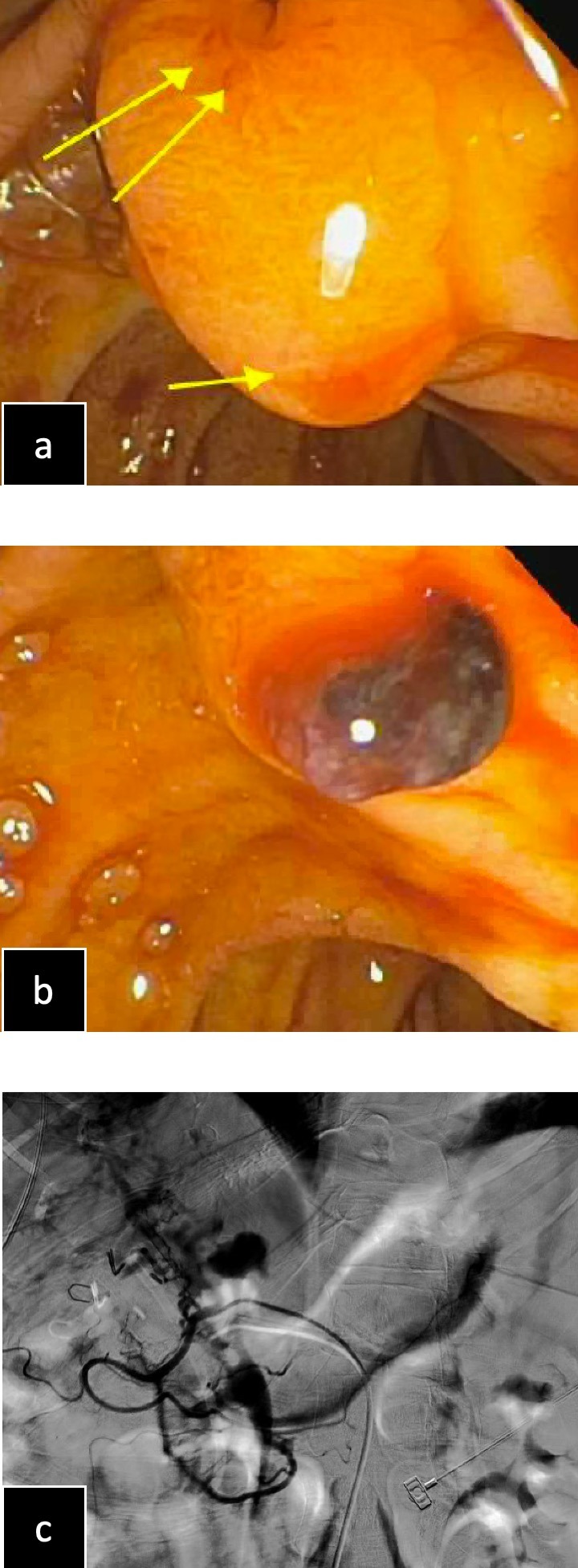

Case Description/Methods: A 52-year-old female with compensated alcoholic cirrhosis and cholecystitis status post cholecystectomy presented with epigastric pain, coffee ground emesis, and bright red blood per rectum. Vitals were stable, hemoglobin 5.9 g/dL, lipase 1570 IU/L, and total bilirubin 10.4 mg/dL. Computed tomography (CT) showed acute pancreatitis with peripancreatic inflammatory changes. After initial resuscitation, EGD revealed active bleeding at the ampulla but no blood in the stomach. Immediate ERCP confirmed hemosuccus pancreaticus (Fig. 1a/1b) and an increased rate of hemorrhage, with bright red blood now pooled in the stomach and duodenum. Patient underwent transcatheter angiography with empiric coil embolization of the GDA, achieving hemostasis (Fig. 1c).

Discussion: Hemosuccus pancreaticus accounts for less than 1% of upper GI bleeds. As clots form and dissolve in the pancreatic duct, subsequent elevations in intraductal pressure lead to waxing and waning abdominal pain, with hemorrhage in the form of melena, hematemesis, or hematochezia. Primary diagnosis relies on direct visualization of the bleed. EGD, an imperative part of the initial workup, rarely reveals active bleeding from the ampulla and is only diagnostic in 30% of cases. More sensitive diagnostic tests include abdominal CT angiography, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), or catheter-based mesenteric angiography. Alternately, both diagnosis and treatment can be accomplished via ERCP, with the side-viewing duodenoscope allowing for a full assessment for pathology of the ampulla, bile duct, and pancreatic duct. Both its intermittent symptoms and anatomic location present significant diagnostic challenges and require early consideration of hemosuccus pancreaticus in the evaluation of obscure GI bleeds. Though it can be evasive, early diagnosis is imperative given the often rapid progression of these bleeds, as displayed in our patient above, and the up to 90% mortality in untreated cases.

Disclosures:

Hannah W. Fiske, MD1, Averill Guo, MD2, Sarah M. Hyder, MD, MBA3. A0069 - Hemosuccus Pancreaticus: More Than at First Blush, ACG 2022 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Charlotte, NC: American College of Gastroenterology.

1Brown University/Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI; 2The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI; 3Lifespan Physician Group - Brown University, East Providence, RI

Introduction: Hemosuccus pancreaticus describes hemorrhage from the ampulla of Vater via the pancreatic duct, and is an infrequent but potentially life-threatening cause of upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Diagnosis can be elusive and treatment challenging. Here we report a case of hemosuccus pancreaticus in the setting of acute pancreatitis identified on upper endoscopy (EGD) and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), treated successfully with gastroduodenal artery (GDA) embolization by interventional radiology.

Case Description/Methods: A 52-year-old female with compensated alcoholic cirrhosis and cholecystitis status post cholecystectomy presented with epigastric pain, coffee ground emesis, and bright red blood per rectum. Vitals were stable, hemoglobin 5.9 g/dL, lipase 1570 IU/L, and total bilirubin 10.4 mg/dL. Computed tomography (CT) showed acute pancreatitis with peripancreatic inflammatory changes. After initial resuscitation, EGD revealed active bleeding at the ampulla but no blood in the stomach. Immediate ERCP confirmed hemosuccus pancreaticus (Fig. 1a/1b) and an increased rate of hemorrhage, with bright red blood now pooled in the stomach and duodenum. Patient underwent transcatheter angiography with empiric coil embolization of the GDA, achieving hemostasis (Fig. 1c).

Discussion: Hemosuccus pancreaticus accounts for less than 1% of upper GI bleeds. As clots form and dissolve in the pancreatic duct, subsequent elevations in intraductal pressure lead to waxing and waning abdominal pain, with hemorrhage in the form of melena, hematemesis, or hematochezia. Primary diagnosis relies on direct visualization of the bleed. EGD, an imperative part of the initial workup, rarely reveals active bleeding from the ampulla and is only diagnostic in 30% of cases. More sensitive diagnostic tests include abdominal CT angiography, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), or catheter-based mesenteric angiography. Alternately, both diagnosis and treatment can be accomplished via ERCP, with the side-viewing duodenoscope allowing for a full assessment for pathology of the ampulla, bile duct, and pancreatic duct. Both its intermittent symptoms and anatomic location present significant diagnostic challenges and require early consideration of hemosuccus pancreaticus in the evaluation of obscure GI bleeds. Though it can be evasive, early diagnosis is imperative given the often rapid progression of these bleeds, as displayed in our patient above, and the up to 90% mortality in untreated cases.

Figure: Figure 1. (a) Biliary orifice (double arrow), pancreatic orifice (single arrow) with active bleeding, seen on ERCP. (b) Blood clot at the ampulla, seen on ERCP. (c) IR transcatheter embolization of the omental branch of the GDA.

Disclosures:

Hannah Fiske indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Averill Guo indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Sarah Hyder indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Hannah W. Fiske, MD1, Averill Guo, MD2, Sarah M. Hyder, MD, MBA3. A0069 - Hemosuccus Pancreaticus: More Than at First Blush, ACG 2022 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Charlotte, NC: American College of Gastroenterology.