Back

Poster Session B - Monday Morning

Category: Colon

B0135 - To Be Colorectal or Not to Be? That Is the Question

Monday, October 24, 2022

10:00 AM – 12:00 PM ET

Location: Crown Ballroom

Has Audio

Estephan Zayat, MD

University of Kansas School of Medicine

Wichita, KS

Presenting Author(s)

Micah Vander Griend, MPH1, Marisa-Nicole Zayat, BS2, Joel Alderson, DO3, Estephan Zayat, MD2

1University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS; 2University of Kansas School of Medicine, Wichita, KS; 3Ascension Via Christi, Wichita, KS

Introduction: Among the elderly, large bowel obstruction is often caused by colorectal cancer. Because prostate cancer is usually slow-growing, it can be asymptomatic and initially be missed, resulting in insidious disease progression.1 Infrequently, prostate cancer can involve the rectum, leading to diagnostic challenges.

Case Description/Methods: A 72-year-old male presented with new-onset lower abdominal pain and constipation, with his last bowel movement occurring two weeks prior. Previous bowel movements were described as small caliber, black, and blood-streaked. During the past six months, he experienced an 80-pound unintentional weight loss, which was unsuccessfully treated with appetite stimulants. He also had hematuria. Pertinent physical exam findings included mild lower abdominal tenderness. Past medical history was significant for metastatic prostate cancer managed with abiraterone acetate, prednisone, and megestrol. Surgical history revealed prostatectomy.

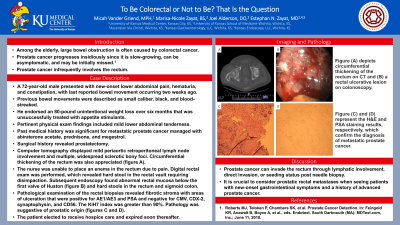

Computer tomography displayed mild periaortic retroperitoneal lymph node involvement and sclerotic bony foci of the ribs, thoracolumbar vertebral bodies, and the lower pelvis suspicious for carcinomatosis. Circumferential thickening of the rectum was also appreciated (figure A).

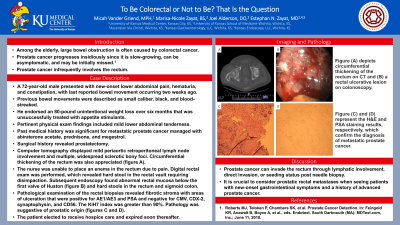

The patient could not be prepped because the nurse was unable to place an enema in the rectum due to pain. Digital rectal exam was performed, which revealed hard stool in the rectal vault requiring disimpaction. Subsequent endoscopy found abnormal rectal mucosa below the first valve of Huston (figure B) and hard stools in the rectum and sigmoid colon.

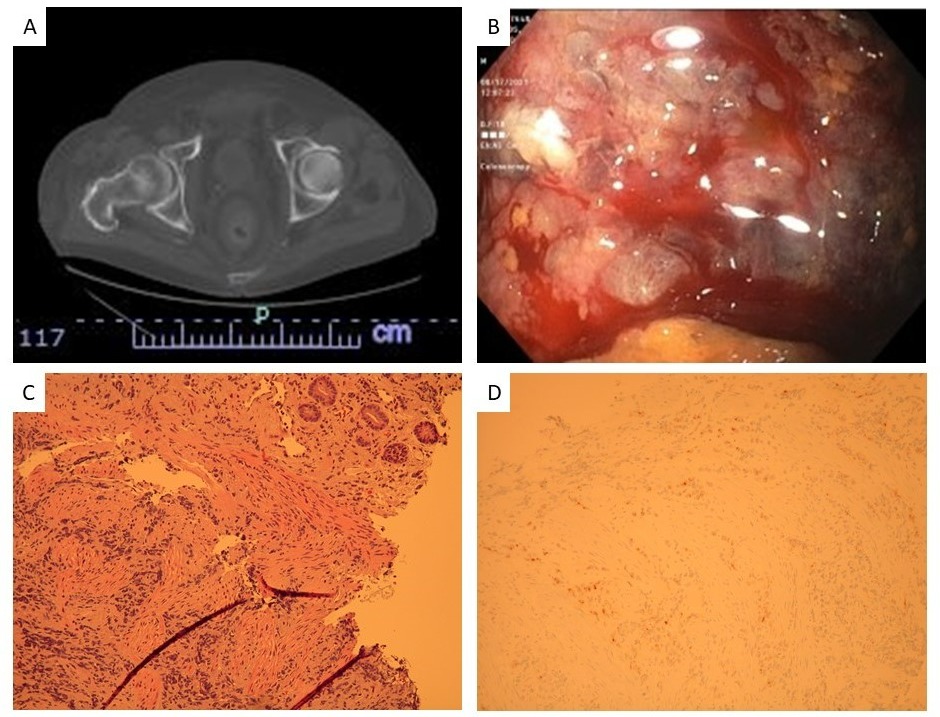

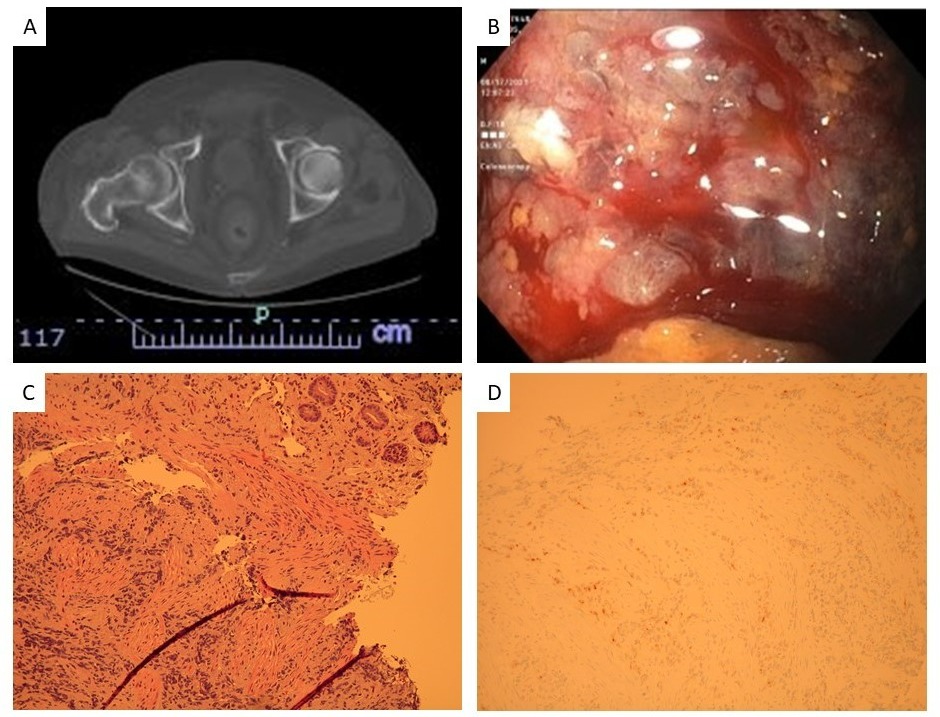

Pathological examination of the rectal biopsies revealed fibrotic stroma with areas of ulceration that were positive for AE1/AE3 and PSA and negative for CMV, CDX-2, synaptophysin, and CD56 with a KiH7 index greater than 90%, suggestive of prostatic origin (figures C and D).

The patient elected to receive hospice care and expired shortly thereafter.

Discussion: Prostate cancer can invade the rectum through lymphatic involvement, through direct invasion, or rarely through seeding status post needle biopsy. Although rare, it is crucial to consider prostatic rectal metastases when seeing patients with new-onset gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. obstruction or bleeding) and a history of advanced prostate cancer.

References

1. Roberts MJ, Teloken P, Chambers SK, et al. Prostate Cancer Detection. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; June 11, 2018.

Disclosures:

Micah Vander Griend, MPH1, Marisa-Nicole Zayat, BS2, Joel Alderson, DO3, Estephan Zayat, MD2. B0135 - To Be Colorectal or Not to Be? That Is the Question, ACG 2022 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Charlotte, NC: American College of Gastroenterology.

1University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS; 2University of Kansas School of Medicine, Wichita, KS; 3Ascension Via Christi, Wichita, KS

Introduction: Among the elderly, large bowel obstruction is often caused by colorectal cancer. Because prostate cancer is usually slow-growing, it can be asymptomatic and initially be missed, resulting in insidious disease progression.1 Infrequently, prostate cancer can involve the rectum, leading to diagnostic challenges.

Case Description/Methods: A 72-year-old male presented with new-onset lower abdominal pain and constipation, with his last bowel movement occurring two weeks prior. Previous bowel movements were described as small caliber, black, and blood-streaked. During the past six months, he experienced an 80-pound unintentional weight loss, which was unsuccessfully treated with appetite stimulants. He also had hematuria. Pertinent physical exam findings included mild lower abdominal tenderness. Past medical history was significant for metastatic prostate cancer managed with abiraterone acetate, prednisone, and megestrol. Surgical history revealed prostatectomy.

Computer tomography displayed mild periaortic retroperitoneal lymph node involvement and sclerotic bony foci of the ribs, thoracolumbar vertebral bodies, and the lower pelvis suspicious for carcinomatosis. Circumferential thickening of the rectum was also appreciated (figure A).

The patient could not be prepped because the nurse was unable to place an enema in the rectum due to pain. Digital rectal exam was performed, which revealed hard stool in the rectal vault requiring disimpaction. Subsequent endoscopy found abnormal rectal mucosa below the first valve of Huston (figure B) and hard stools in the rectum and sigmoid colon.

Pathological examination of the rectal biopsies revealed fibrotic stroma with areas of ulceration that were positive for AE1/AE3 and PSA and negative for CMV, CDX-2, synaptophysin, and CD56 with a KiH7 index greater than 90%, suggestive of prostatic origin (figures C and D).

The patient elected to receive hospice care and expired shortly thereafter.

Discussion: Prostate cancer can invade the rectum through lymphatic involvement, through direct invasion, or rarely through seeding status post needle biopsy. Although rare, it is crucial to consider prostatic rectal metastases when seeing patients with new-onset gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. obstruction or bleeding) and a history of advanced prostate cancer.

References

1. Roberts MJ, Teloken P, Chambers SK, et al. Prostate Cancer Detection. In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., eds. Endotext. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; June 11, 2018.

Figure: Figure (A) depicts circumferential thickening of the rectum on CT and (B) a rectal ulcerative on colonoscopy. (C) H&E and (D) PSA immunohistochemical staining confirm the diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer.

Disclosures:

Micah Vander Griend indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Marisa-Nicole Zayat indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Joel Alderson indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Estephan Zayat indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Micah Vander Griend, MPH1, Marisa-Nicole Zayat, BS2, Joel Alderson, DO3, Estephan Zayat, MD2. B0135 - To Be Colorectal or Not to Be? That Is the Question, ACG 2022 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Charlotte, NC: American College of Gastroenterology.