Back

Poster Session D - Tuesday Morning

Category: Small Intestine

D0674 - Small Bowel Diverticulosis and Malrotation: A New Spin on SIBO

Tuesday, October 25, 2022

10:00 AM – 12:00 PM ET

Location: Crown Ballroom

Has Audio

Pablo S. Santander, MD, MS

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center

Bethesda, MD

Presenting Author(s)

Pablo S. Santander, MD, MS, Andrew Mertz, MD, Lawrence Goldkind, MD

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD

Introduction: Small bowel diverticula are far less common than colonic diverticulosis. Formative mechanisms, including abnormal peristaltic activity and high intraluminal pressures, are shared between both varieties. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is defined by an abnormal abundance of bacteria in the small bowel, typically associated with abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea. Small bowel diverticula can predispose for SIBO. The constellation of symptoms is commonly attributed to or misdiagnosed as functional bowel syndromes. When appropriately recognized and treated, symptoms associated with bacterial overgrowth can be exquisitely responsive to antibiotic therapy.

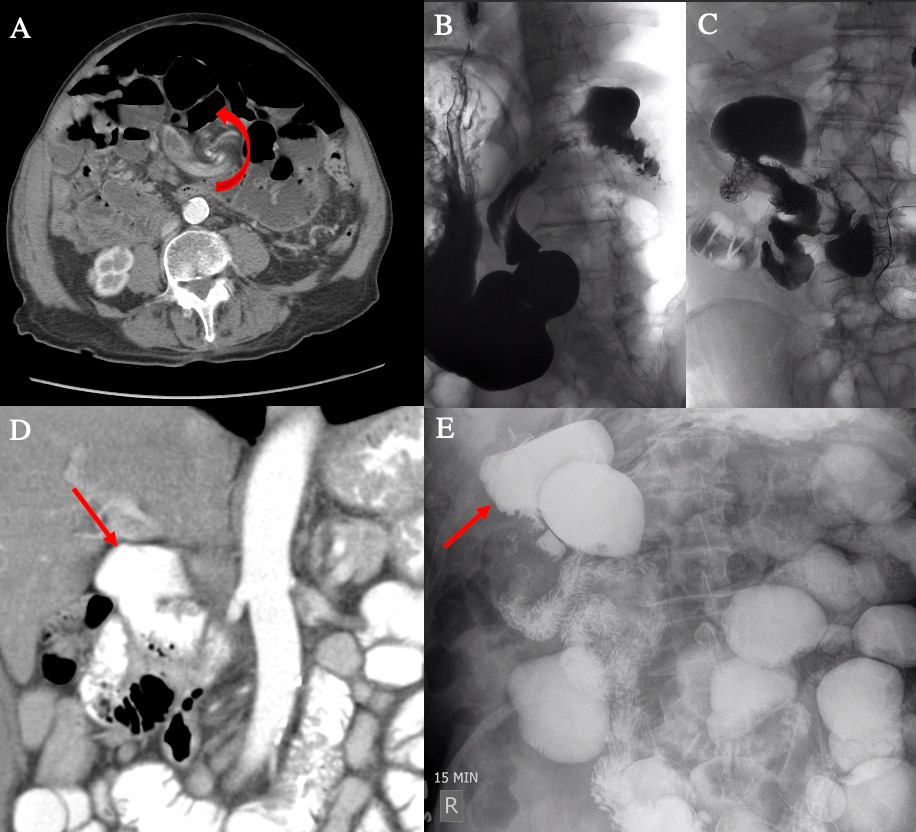

Case Description/Methods: Our case involves a 93-year-old man with over ten years of chronic abdominal bloating, distension, watery stools, and intermittent, focal postprandial epigastric pain. Computed tomography imaging was significant for evidence of malrotation and focal caliber change within the small intestine (Figure 1A, 1D). Real-time fluoroscopic exam of barium traversing the duodenum revealed preferential filling of the large duodenal diverticulum rather than the true duodenal lumen (1B, 1C). An upper gastrointestinal series revealed a corkscrew appearance of the duodenum, a 6.3-centimeter proximal post-bulbar duodenal diverticulum, and multiple jejunal and ileal large multi-centimeter diverticula (1E). The collection of small bowel diverticular disease was postulated to cause a secondary bacterial overgrowth and focal epigastric discomfort given the degree of contrast stasis. He started a 10-day trial of rifaximin with prompt and dramatic clinical improvement. He experienced recrudescence of symptoms every few months and was managed with courses of rifaximin with good symptomatic control. The patient was also responsive to a full liquid diet aimed to reduce luminal distension.

Discussion: Our patient’s anatomy and symptomatology suggest a linear causality that started with anatomic malrotation leading to intermittent increases in luminal pressures. This predisposed him for small bowel diverticula formation, which ultimately lead to stasis and a nidus for SIBO. There are isolated case reports of an association between malrotation and extensive small bowel diverticulosis. We present this case to alert physicians that “incidentally” found malrotation may be associated with symptomatic physiologic sequelae including SIBO.

Disclosures:

Pablo S. Santander, MD, MS, Andrew Mertz, MD, Lawrence Goldkind, MD. D0674 - Small Bowel Diverticulosis and Malrotation: A New Spin on SIBO, ACG 2022 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Charlotte, NC: American College of Gastroenterology.

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD

Introduction: Small bowel diverticula are far less common than colonic diverticulosis. Formative mechanisms, including abnormal peristaltic activity and high intraluminal pressures, are shared between both varieties. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is defined by an abnormal abundance of bacteria in the small bowel, typically associated with abdominal pain, bloating, and diarrhea. Small bowel diverticula can predispose for SIBO. The constellation of symptoms is commonly attributed to or misdiagnosed as functional bowel syndromes. When appropriately recognized and treated, symptoms associated with bacterial overgrowth can be exquisitely responsive to antibiotic therapy.

Case Description/Methods: Our case involves a 93-year-old man with over ten years of chronic abdominal bloating, distension, watery stools, and intermittent, focal postprandial epigastric pain. Computed tomography imaging was significant for evidence of malrotation and focal caliber change within the small intestine (Figure 1A, 1D). Real-time fluoroscopic exam of barium traversing the duodenum revealed preferential filling of the large duodenal diverticulum rather than the true duodenal lumen (1B, 1C). An upper gastrointestinal series revealed a corkscrew appearance of the duodenum, a 6.3-centimeter proximal post-bulbar duodenal diverticulum, and multiple jejunal and ileal large multi-centimeter diverticula (1E). The collection of small bowel diverticular disease was postulated to cause a secondary bacterial overgrowth and focal epigastric discomfort given the degree of contrast stasis. He started a 10-day trial of rifaximin with prompt and dramatic clinical improvement. He experienced recrudescence of symptoms every few months and was managed with courses of rifaximin with good symptomatic control. The patient was also responsive to a full liquid diet aimed to reduce luminal distension.

Discussion: Our patient’s anatomy and symptomatology suggest a linear causality that started with anatomic malrotation leading to intermittent increases in luminal pressures. This predisposed him for small bowel diverticula formation, which ultimately lead to stasis and a nidus for SIBO. There are isolated case reports of an association between malrotation and extensive small bowel diverticulosis. We present this case to alert physicians that “incidentally” found malrotation may be associated with symptomatic physiologic sequelae including SIBO.

Figure: A - Axial computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen with intravenous contrast demonstrating splanchnic swirling.

B - Real-time barium swallow with view of the esophagus, stomach, pylorus, and proximal duodenum with large diverticulum.

C - Oblique view of large proximal duodenal diverticulum with preferential filling and contrast stasis.

D - Coronal CT of the abdomen with oral contrast with large proximal duodenal diverticulum.

E - Abdominal x-ray with delayed oral contrast medium showing innumerable small bowel diverticula.

B - Real-time barium swallow with view of the esophagus, stomach, pylorus, and proximal duodenum with large diverticulum.

C - Oblique view of large proximal duodenal diverticulum with preferential filling and contrast stasis.

D - Coronal CT of the abdomen with oral contrast with large proximal duodenal diverticulum.

E - Abdominal x-ray with delayed oral contrast medium showing innumerable small bowel diverticula.

Disclosures:

Pablo Santander indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Andrew Mertz indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Lawrence Goldkind indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Pablo S. Santander, MD, MS, Andrew Mertz, MD, Lawrence Goldkind, MD. D0674 - Small Bowel Diverticulosis and Malrotation: A New Spin on SIBO, ACG 2022 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Charlotte, NC: American College of Gastroenterology.