Back

Poster Session E - Tuesday Afternoon

Category: GI Bleeding

E0331 - Upper GI Bleed Caused by Ampullary AVM

Tuesday, October 25, 2022

3:00 PM – 5:00 PM ET

Location: Crown Ballroom

Has Audio

Mina Rismani, BS

University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville

Greenville, SC

Presenting Author(s)

Mina Rismani, BS1, Monia Werlang, MD2, Veeral Oza, MD2

1University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville, Greenville, SC; 2University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville, Prisma Health, Greenville, SC

Introduction: GI bleed (GIB) is responsible for 1,000,000+ hospitalizations every year, and a mortality rate of 2-10%. Ampullary AVMs are an uncommon etiology of GIB and difficult from a diagnostic standpoint. We present a case of 77-year-old man presenting to emergency department (ED) with acute shortness of breath (SOB) and chest pain (CP), and dark stools for 4 days, found to have acute GIB caused by ampullary AVM.

Case Description/Methods: 77-year-old white male presented to ED with acute SOB and CP. Past medical history included aortic regurgitation s/p valve replacement, atrial fibrillation s/p ablation and watchman, chronic anemia with baseline Hgb of 9, HTN, HFpEF, and ulcerative colitis s/p curative total proctocolectomy and ileostomy with modified Kock pouch procedure.

Physical exam was unremarkable aside from dark-appearing ileal pouch output. He was not on anticoagulation and denied Pepto-Bismol use. Abnormal labs included Hgb/Hct of 5.1/16.4, BUN:Cr 37:1.93, and hemoccult positive stool from ileal pouch. Presenting symptoms of anemia (CP, SOB) were consistent with lab findings, concerning for GIB in setting of hemoccult positive stool.

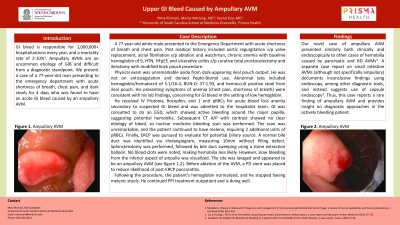

He received IV Protonix, Rocephin, and 1u pRBCs for acute blood loss anemia secondary to suspected GIB and was admitted to hospitalist. GI was consulted to do EGD, which showed active bleeding around major papilla, suggesting hemobilia. Subsequent CT A/P with contrast showed no clear etiology of bleed, so nuclear medicine bleeding scan was performed. The scan was unremarkable, and he continued to have melena, requiring 2u of pRBCs. Finally, ERCP was pursued to evaluate for potential biliary source. A normal bile duct (BD) was identified via cholangiogram, measuring 10mm without filling defect. Sphincterotomy was performed, followed by BD sweeping using a stone extraction balloon. No blood clots were noted, making hemobilia less likely. However, slow bleeding from inferior aspect of ampulla was visualized. The site was lavaged and appeared to be ampullary AVM (see figure 1). Before ablation of AVM, a PD stent was placed to reduce likelihood of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Following procedure, his Hgb normalized, and he stopped having melenic stools. He continued PPI treatment outpatient and is doing well.

Discussion: To our knowledge, no case of GIB caused by ampullary AVM is found in the literature. Thus, this case reports a rare finding of ampullary AVM and provides support for endoscopy as diagnostic approach in such patients.

Disclosures:

Mina Rismani, BS1, Monia Werlang, MD2, Veeral Oza, MD2. E0331 - Upper GI Bleed Caused by Ampullary AVM, ACG 2022 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Charlotte, NC: American College of Gastroenterology.

1University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville, Greenville, SC; 2University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville, Prisma Health, Greenville, SC

Introduction: GI bleed (GIB) is responsible for 1,000,000+ hospitalizations every year, and a mortality rate of 2-10%. Ampullary AVMs are an uncommon etiology of GIB and difficult from a diagnostic standpoint. We present a case of 77-year-old man presenting to emergency department (ED) with acute shortness of breath (SOB) and chest pain (CP), and dark stools for 4 days, found to have acute GIB caused by ampullary AVM.

Case Description/Methods: 77-year-old white male presented to ED with acute SOB and CP. Past medical history included aortic regurgitation s/p valve replacement, atrial fibrillation s/p ablation and watchman, chronic anemia with baseline Hgb of 9, HTN, HFpEF, and ulcerative colitis s/p curative total proctocolectomy and ileostomy with modified Kock pouch procedure.

Physical exam was unremarkable aside from dark-appearing ileal pouch output. He was not on anticoagulation and denied Pepto-Bismol use. Abnormal labs included Hgb/Hct of 5.1/16.4, BUN:Cr 37:1.93, and hemoccult positive stool from ileal pouch. Presenting symptoms of anemia (CP, SOB) were consistent with lab findings, concerning for GIB in setting of hemoccult positive stool.

He received IV Protonix, Rocephin, and 1u pRBCs for acute blood loss anemia secondary to suspected GIB and was admitted to hospitalist. GI was consulted to do EGD, which showed active bleeding around major papilla, suggesting hemobilia. Subsequent CT A/P with contrast showed no clear etiology of bleed, so nuclear medicine bleeding scan was performed. The scan was unremarkable, and he continued to have melena, requiring 2u of pRBCs. Finally, ERCP was pursued to evaluate for potential biliary source. A normal bile duct (BD) was identified via cholangiogram, measuring 10mm without filling defect. Sphincterotomy was performed, followed by BD sweeping using a stone extraction balloon. No blood clots were noted, making hemobilia less likely. However, slow bleeding from inferior aspect of ampulla was visualized. The site was lavaged and appeared to be ampullary AVM (see figure 1). Before ablation of AVM, a PD stent was placed to reduce likelihood of post-ERCP pancreatitis.

Following procedure, his Hgb normalized, and he stopped having melenic stools. He continued PPI treatment outpatient and is doing well.

Discussion: To our knowledge, no case of GIB caused by ampullary AVM is found in the literature. Thus, this case reports a rare finding of ampullary AVM and provides support for endoscopy as diagnostic approach in such patients.

Figure: Figure 1. Ampullary AVM.

Disclosures:

Mina Rismani indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Monia Werlang indicated no relevant financial relationships.

Veeral Oza: Boston Scientific – Consultant. S4 Medical – Advisor or Review Panel Member.

Mina Rismani, BS1, Monia Werlang, MD2, Veeral Oza, MD2. E0331 - Upper GI Bleed Caused by Ampullary AVM, ACG 2022 Annual Scientific Meeting Abstracts. Charlotte, NC: American College of Gastroenterology.